Disney’s The Jungle Book, released in 1967, was a huge box office success. The film was praised highly for its attention to voice casting as a primary identifier of character’s personality and animation. Unfortunately, it is this exact quality which creates some problematic issues.

The monkeys of the jungle are racially coded as black, a problematic choice of animal characterization, and further worsened by aural stereotypes. In their essay “The Movie You See, The Movie You Don’t,” scholars Susan Miller and Greg Rhode note that “Jungle Book frequently relies on verbal class and gender stereotyping for its “innocent” fun, displacing the visual black and white of Song of the South onto aural stereotypes.” While the animation of monkeys would clearly not be racist, specifically representing those monkeys as African American puts the innocence of intentions a little more into question.

The very lyrics and style of the song King Louis sings become quickly controversial in light of the black coded nature assigned to his character. The famous song, “I Want to Be Like You” which King Louis and the monkeys sing, is all about the desire they hold to be human. The refraining chorus states: “Ooh, ooh, oh! I wanna be like you, I wanna walk like you, talk like you, too ooh, ooh. You’ll see it’s true, ooh, ooh! An ape like me, ee, ee. Can learn to be Juoo ooh man, too ooh, ooh.” Writing an entire song about the monkeys desiring recognition as humans, and clearly coding those monkeys as black poses an incredibly racist issue in the film, highly inappropriate for a children’s animation.

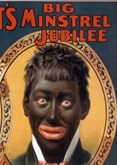

Next, the issue of the black coded nature becomes further problematic by the fact that they are once again played by white actors. Just as Jim Crow in Dumbo was voiced by white actor Cliff Edwards, so King Louis is voiced by white actor Louis Prima. While it would clearly be racist to choose African American voices to present these stereotypes, it is in many ways worse to choose a white actor to play a clear racial stereotype as this is the exact premise behind blackface minstrel performances.

Even within the plot of jungle book itself, the idea of minstrelsy is promoted by the fact that Baloo dresses up in monkey attire, and proceeds to imitate and sing the same song as King Louis. Baloo, as a non-monkey, donning “monkeyface” and performing in exaggerated style, his perceived understanding of what that means, is a close parallel to blackface in which a white, dons “blackface” and proceeds to imitate a black coded performance based on offensive stereotypes.

Comparing the images of Baloo in monkey attire, with images of blackface performers, once again the similarities are disturbingly similar. The hair, large lips, cartoonish body language, Baloo is clearly putting on a blackface performance with King Louis.

The images and parallels, promotion and reinforcement of blackface minstrel performance in today’s society is still present and alive in areas many don’t realize. Perhaps more disturbing is attempting to understand how to respond to such images in our culture. It is difficult to determine the intentionality of these types of images and stereotypes present in The Jungle Book. Are the creators deliberately placing racist material in their films, or are these simply embedded structures that people promote without realizing or understanding the implications of their meaning? Would boycotting any film which presents these stereotypes prove helpful in any regard? Ultimately, the only way that a society can change is through each individual influence on it. Becoming better educated in historical traditions, mistakes, and problems can help us become more aware of them in today’s society and prevent us from incorporating them into our own productions of art, actions, or words. By understanding the history of traditions such as blackface and minstrelsy we can become more aware of their presence in films such as The Jungle Book and make better judgments and criticisms of their problematic issues and hopefully prevent the continuation of them in future films.

Works Cited:

Miller, Susan, and Greg Rode. “The Movie You See, The Movie You Don’t.” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture.” Ed. Bell, Elizabeth, and Lynda Haas, Laura Sells. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. 86-103. Print.