The entry on Grove Music Online under “Cakewalk” describes an origin of the contest from slaves on plantations in the American South. Claude Conyer, the author, explains how the dance became a “strutting parade” parodying the fancy manners of the white slaveholders. In Conyer’s origin story, the first cakewalks happened around 1850 and inspired the popular comedic minstrel shows that were all the rage. However, minstrel shows were popular earlier on, beginning in the 1820s and continuing with the Virginia Minstrels’ first show in 1843.

Which came first? Did slaves dress to the nines in order to make fun of the overly glamorous plantation owners, therefore creating a political statement? Or did minstrels originate the “Zip Coon” figure, dressed to the nines as a favorite stereotype?

Does it matter?

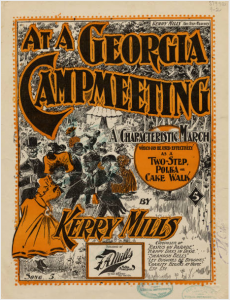

Conyer’s simple statement is an example of the entire history of minstrel song and the misappropriation of Black Americans in minstrelsy. He goes on to describe how the dance was performed as a grand parade entrance, dancers wearing ridiculously fashionable attire and exaggerating every gesture. The accompanying music to the cakewalk often contained characteristics of early ragtime: syncopated rhythms and leaping bass lines. One example of a two-step or cakewalk piece is Kerry Mills’ “At a Georgia Camp Meeting,” composed in 1897.

——

1st Verse

A camp meeting took place,

by the colored race;

Way down in Georgia

There were coons large and small,

lanky lean fat and tall,

At this great coon camp-meeting.

Chorus

When that band of darkies began to play

Pretty music so gay hats were then thrown away

Thought them foolish coons their necks would break

When they quit laughing and talking

And went to walking, for a big choc’late cake.

The lyrics to this piece describe a culture without substance, intelligence, or more than base desires. Every person at the gathering is labeled as a “coon,” and the “foolish coons” walk a cakewalk because no desire could be greater than a chocolate cake.

Although Sterns in Jazz Dance explains that “Negro specialists…everywhere were much in demand” (Stearns 42), it is obvious that even those attending cakewalks were only looking for material to be used as commercial gain. The endearingly simple “coon” sold seats and gained laughter and applause. But now the history of minstrelsy, more well-preserved than the history of Black culture, corrupts what we actually attribute to Black Americans.

Now that takes the cake.

Sources

. “Cakewalk.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed April 14, 2015, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2092374.

Stearns, Marshall and Jean. Jazz Dance : The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968.

“At a Georgia Camp Meeting.” Kerry Mills. :: Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music. Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music. Web. 14 Apr. 2015. <http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/fa-spnc/id/14135/show/14129/rec/4>.