Today, the majority of congregations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America use the most recent book of worship, Evangelical Lutheran Worship, published by Augsburg Fortress, Minneapolis in 2006. Before that time, congregations mostly used the 1978 Lutheran Book of Worship. 20 years prior to the release of LBW, the red Service Book and Hymnal was printed.

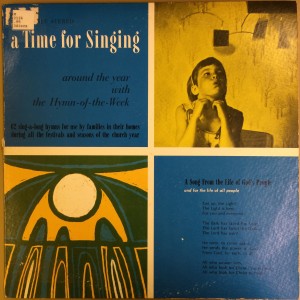

In the year 1971, Dale Warland, most famously known for having conducted the Dale Warland Singers in St. Paul until 2004, and Paul Manz, well-known organist in the Minneapolis area, recruited a chamber choir, and small brass ensemble to record 62 hymns representing the entirety of the church year. Recorded by Lutheran Records, it was distributed by Augsburg Publishing House in Minneapolis.

As the subtitle suggests, this record was meant for families to play in their own homes as a way of learning hymns and worshipping at home. Between each track is a 10-second band of silence so as to find each track easily.

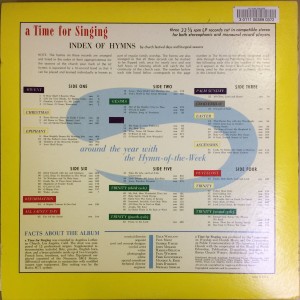

The back of the record sleeve indexes the hymns used to outline the church year. Next to each hymn, there are two numbers. One represents the page number where the hymn can be found in Augsburg’s The Hymn-of-the-Week Songbook. The second number, preceded by “SBH” represents the hymn number of its occurrence in the 1958 Service Book and Hymnal. The inclusion of these referential numbers makes these records an accessible teaching tool. Those families that want to teach their children about classic hymns, or those that want to worship in their own home, are able to locate each hymn with ease, both on the record, and in their songbook or book of worship.

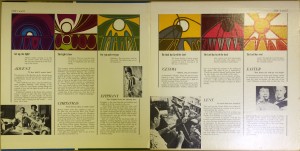

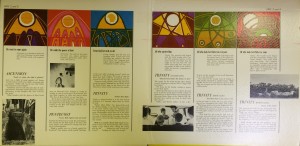

Within the record sleeve are paragraphs explaining each of the seasons and high feasts of the church year. These paragraphs give the listeners and worshippers a little context of how each hymn fits in with the corresponding season or feast.

I think this is a very fun and effective way of introducing hymns to homes. Unlike many CDs today, this record is very interactive. Given the size of these LPs, there is plenty of jacket space to provide very useful and pertinent information. What makes it more musically appealing is the fact that the musicians are not your average church musicians or church choir. Paul Manz and Dale Warland have established themselves in the organist and choral worlds as being phenomenal musicians. There is no information about who the singers are, other than “12 professional singers,” but under the direction of Dale Warland, they are superb.

As a Church Music major, this record makes me want to go out and purchase a turntable and listen to it all the time!

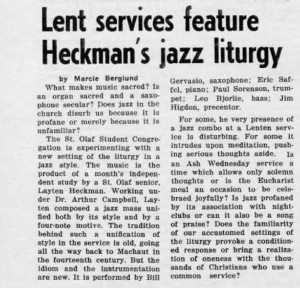

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

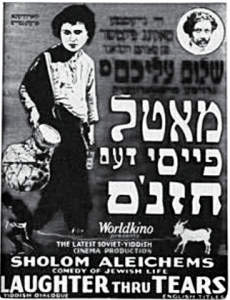

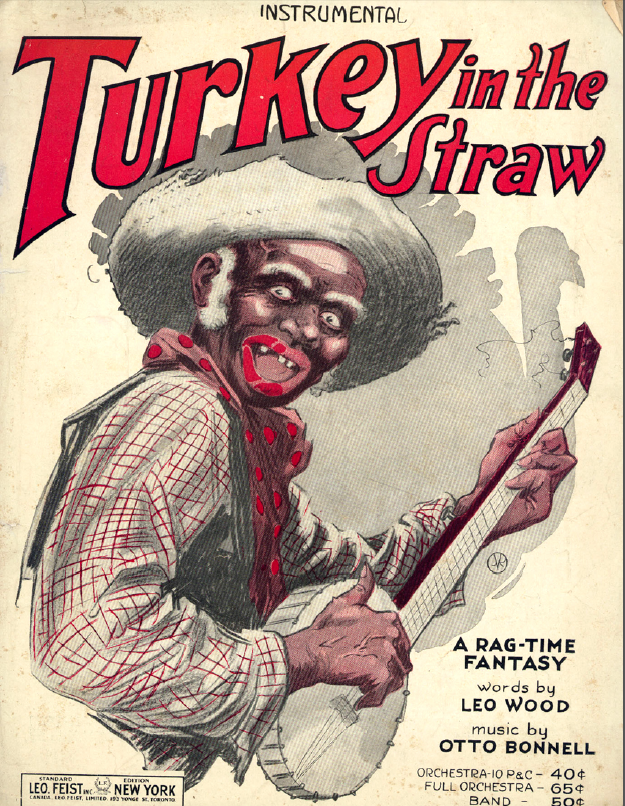

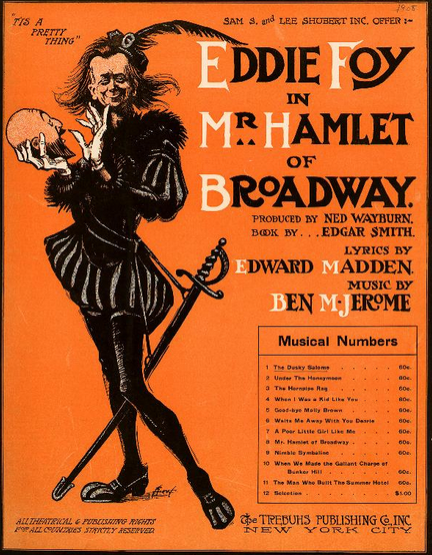

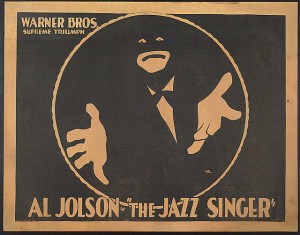

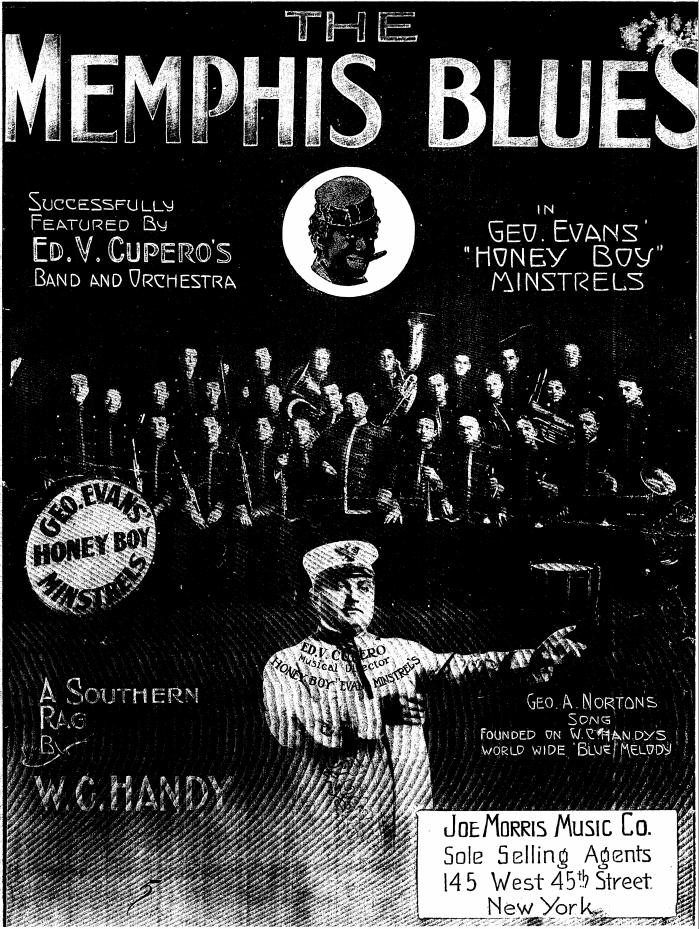

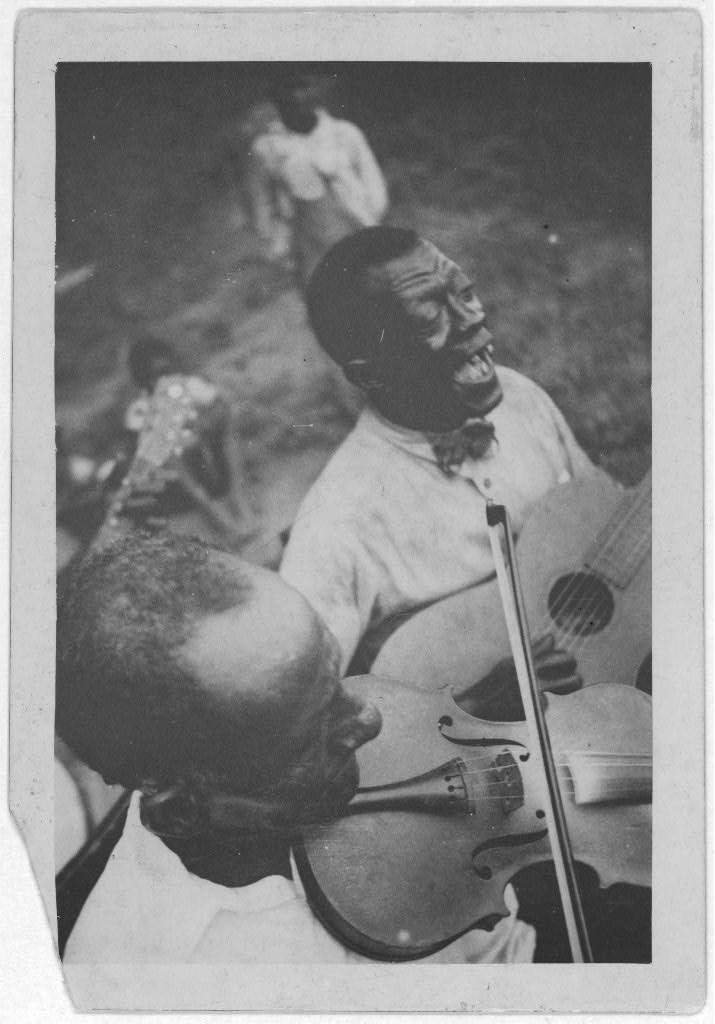

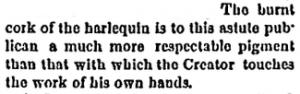

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.

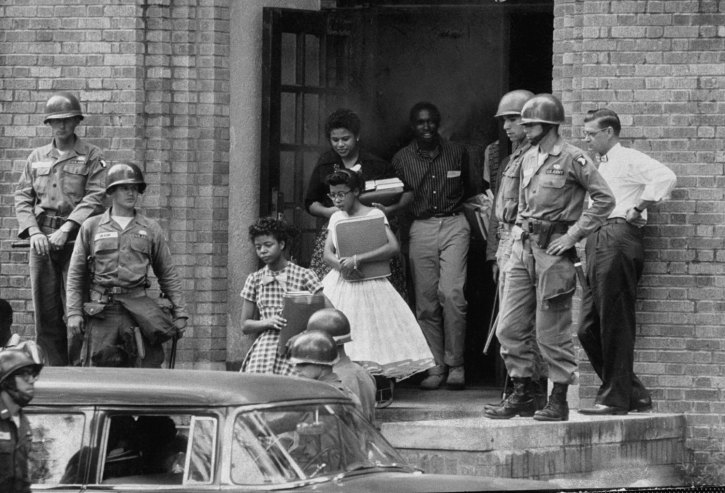

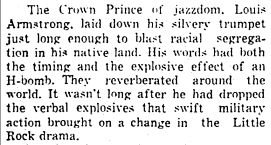

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Armstrong was furious at the discrimination faced by the Little Rock Nine and did not hold back. In what was described as having the “explosive effect of an H-bomb”

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000. Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

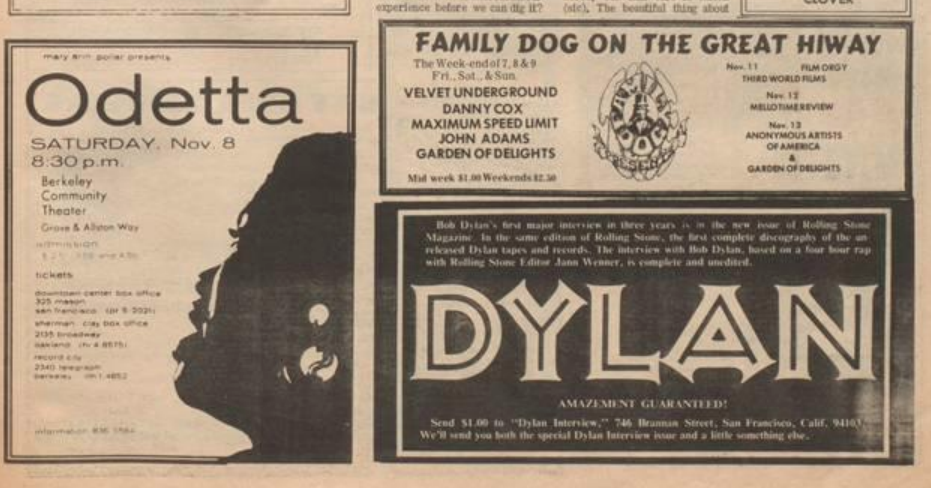

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

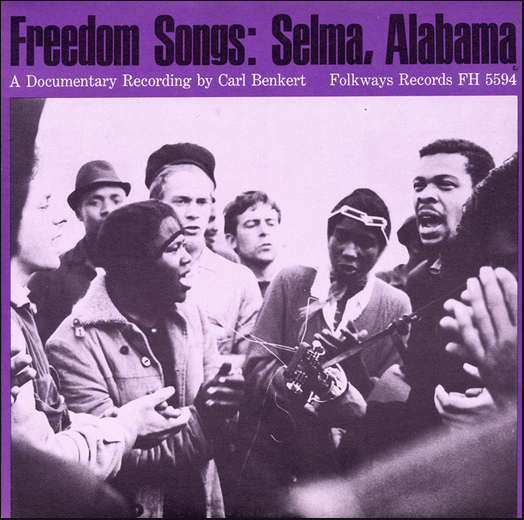

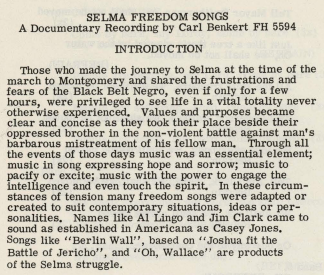

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

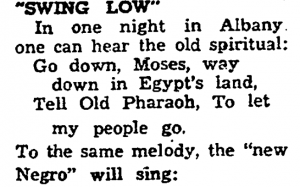

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

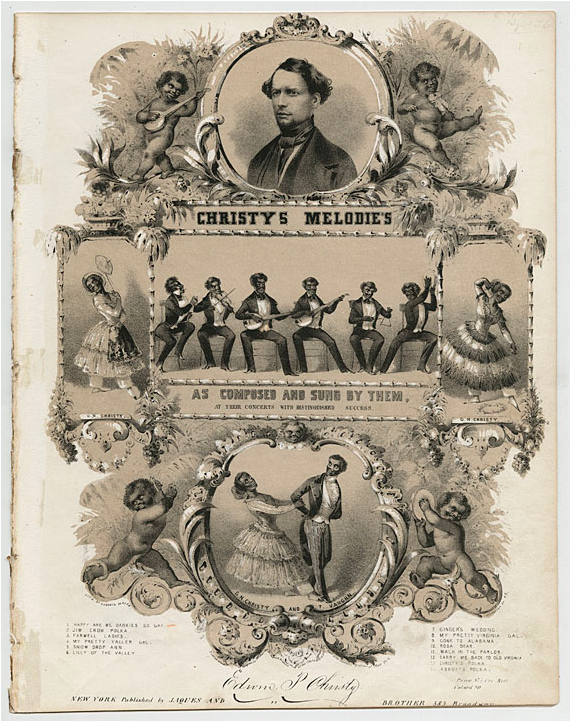

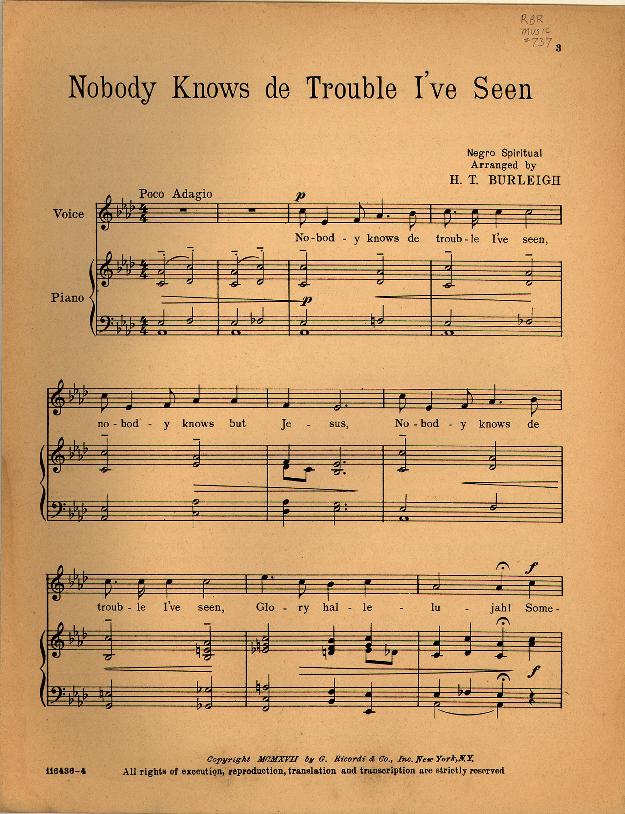

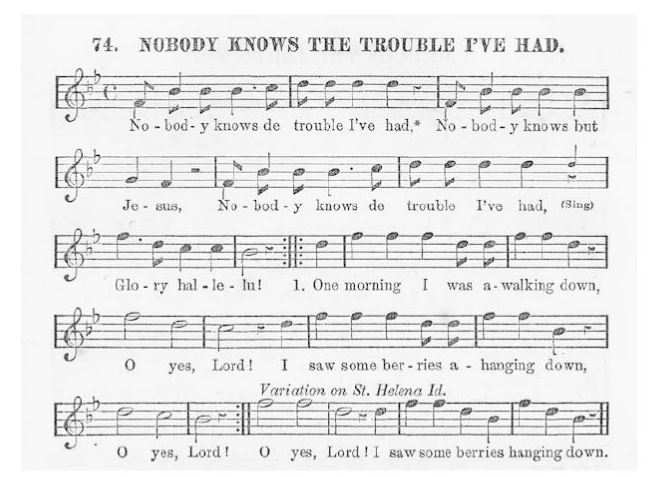

Figure 2

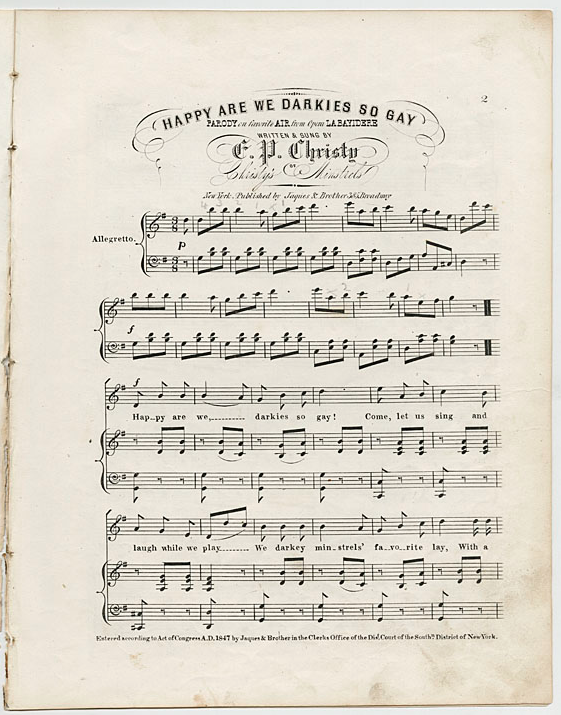

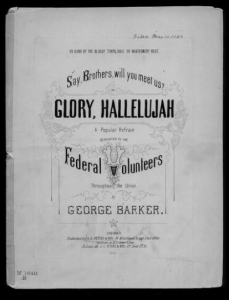

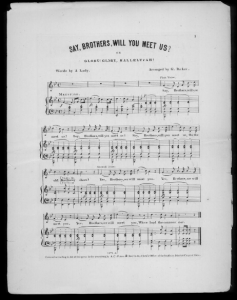

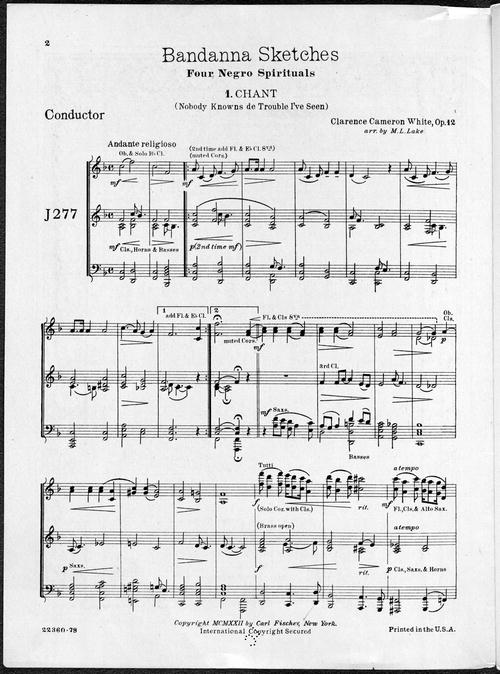

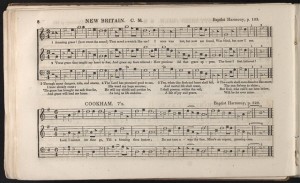

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3

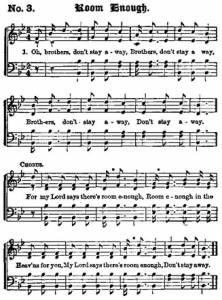

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers. The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

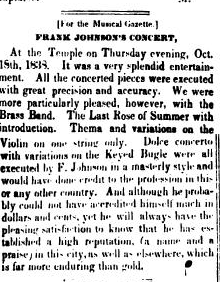

![[Francis Johnson.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1257971&t=r)

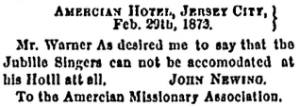

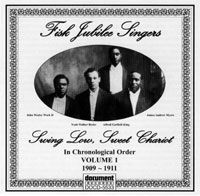

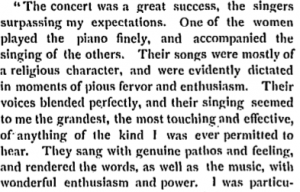

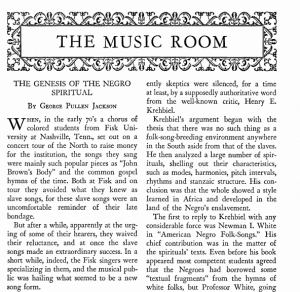

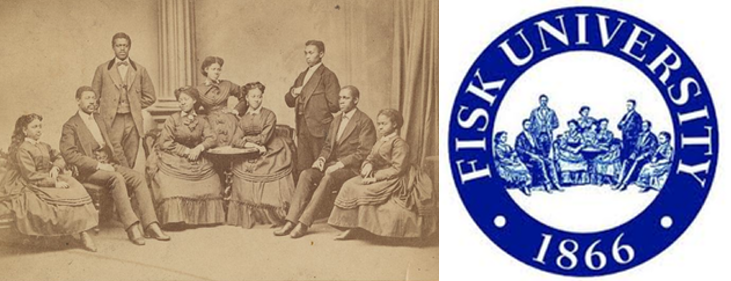

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

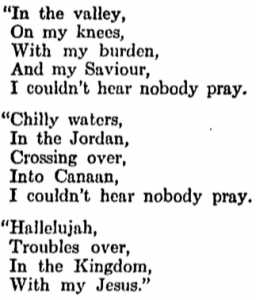

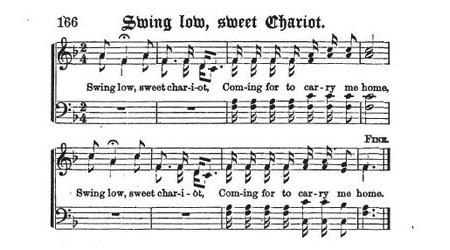

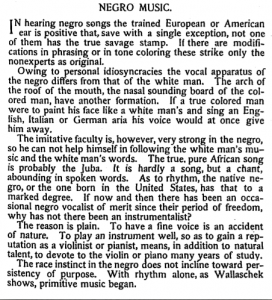

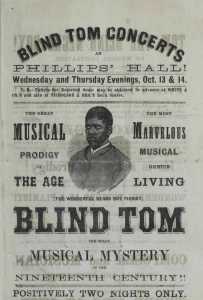

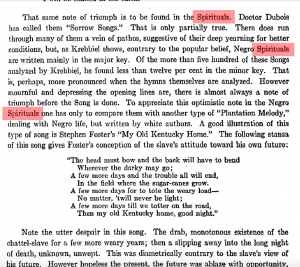

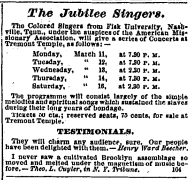

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

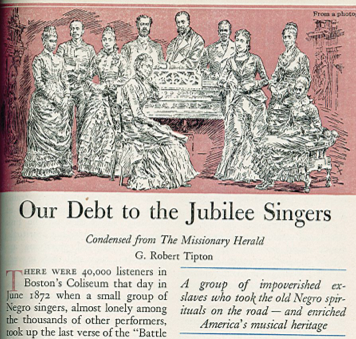

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.