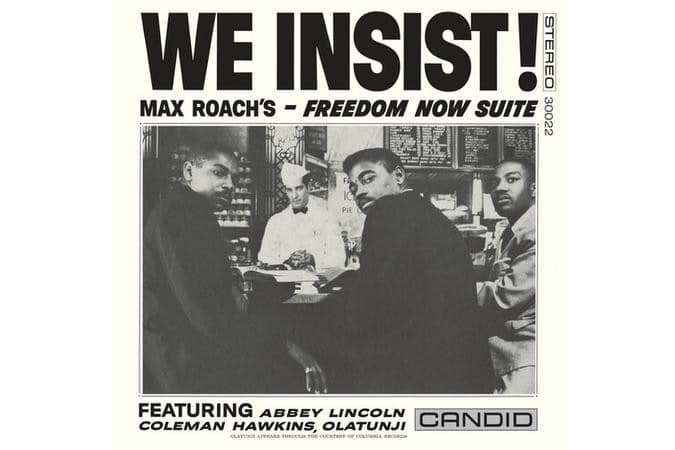

Porgy and Bess is the only Opera in the Canon that portrays a story of Black American people… and it was written by white people.

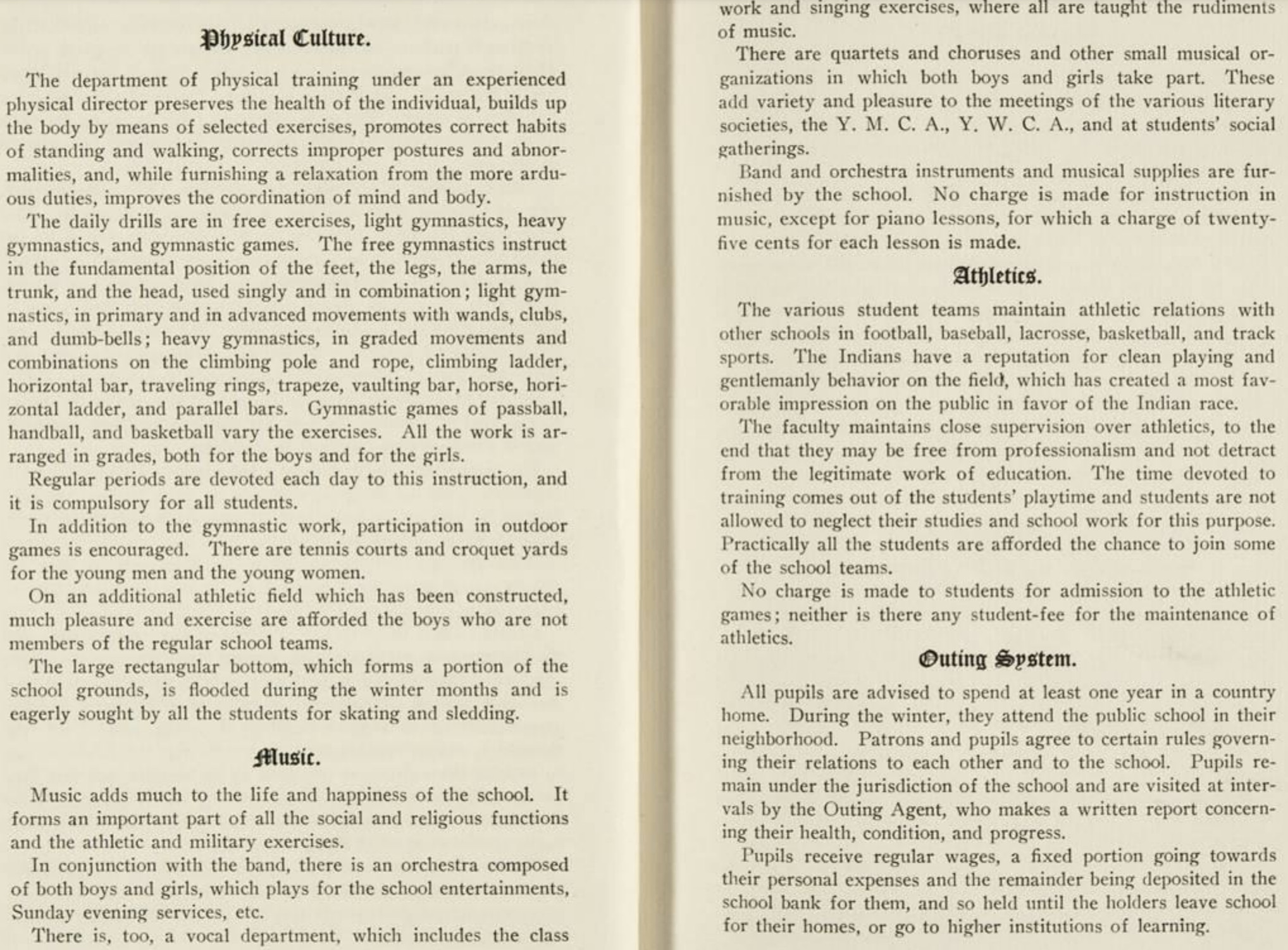

George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess has long been hailed as an iconic work in American opera, blending classical music with jazz, blues, and folk influences to tell the story of life in a fictional African American community in Charleston, South Carolina.1 While its music is undoubtedly powerful, Porgy and Bess also requires critical interrogation, particularly due to the opera’s portrayal of race, culture, and identity. This raises uncomfortable questions about representation, authenticity, and the perpetuation of racial stereotypes.

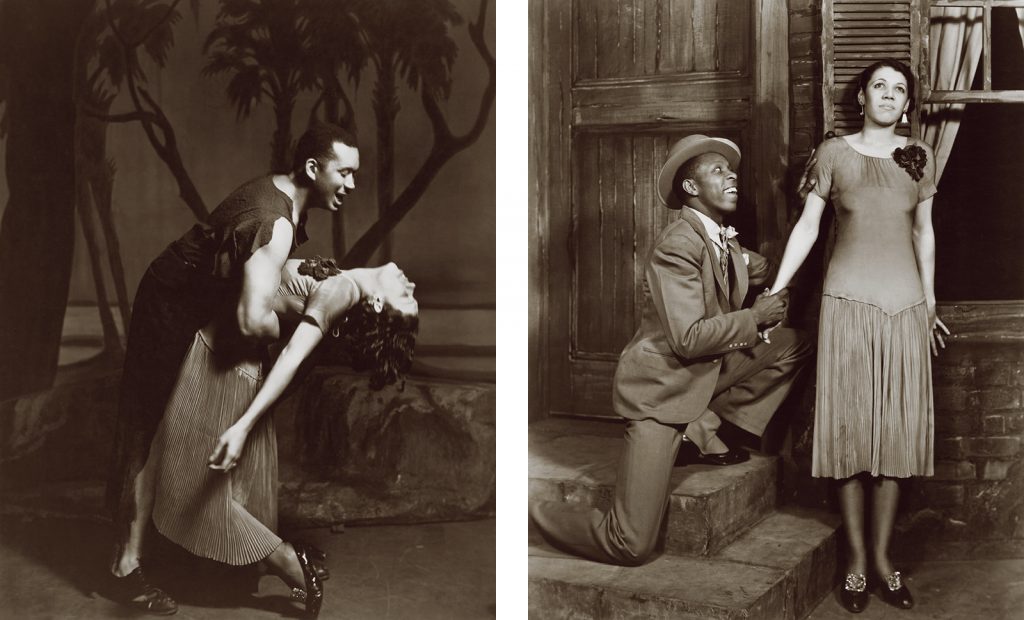

At the heart of Porgy and Bess is a narrative of struggle, love, and survival,2 centered on the character of Porgy, a disabled beggar, and his troubled relationship with Bess, a woman caught in the grip of addiction and abuse. The opera’s setting—Catfish Row, a poor African American neighborhood—creates a world where the characters’ lives are defined by poverty, violence, and hardship. While this portrayal is grounded in the socio-economic realities of many Black communities in the early 20th century, it also risks reinforcing a reductive and stereotypical image of African American life.3

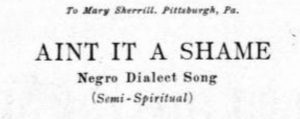

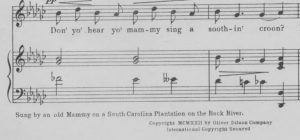

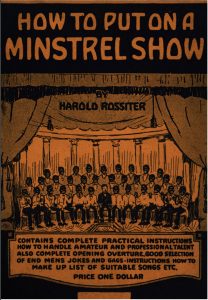

The opera’s focus on African American characters, often depicted in crisis or dependency, can be seen as problematic. Critics have noted that Porgy and Bess is deeply influenced by a white gaze, one that both romanticizes and victimizes African Americans. While Gershwin was committed to incorporating Black music traditions into his work, his portrayal of Black life lacks the nuance and agency that would allow African American characters to transcend their circumstances.3 Each character fits the minstrel stereotypes: either asexual or overly sexual. Either unintelligent or villainous. These reinforce patriarchal white-supremacist ideology that perpetuates a false narrative further.

Modern productions of Porgy and Bess, have sparked important conversations about how the work can be reimagined.2 These revivals attempt to acknowledge the complexities of race and representation, offering opportunities for greater authenticity and racial equity in performances.

Yet, even in its reinvention, Porgy and Bess remains a product of its time—one that must be engaged with critically to understand the tensions between artistic excellence and the reproduction of harmful racial stereotypes.

Ultimately, Porgy and Bess poses a challenge to contemporary audiences. While it is undeniable that the opera has shaped the American musical landscape, its legacy also serves as a reminder that the only work centered around the African American experience was written by white people and serves at perpetuate minstrel stereotypes. To truly recognize the richness of Black identity and culture, it is necessary to interrogate the ways in which works like Porgy and Bess both distort and reflect the lived experiences of Black communities.

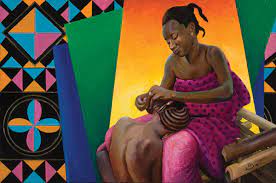

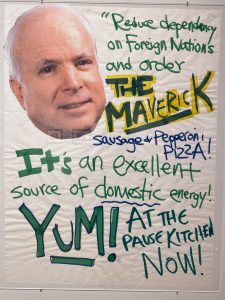

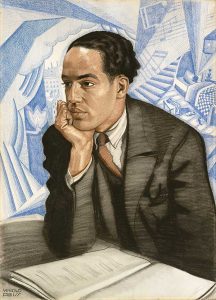

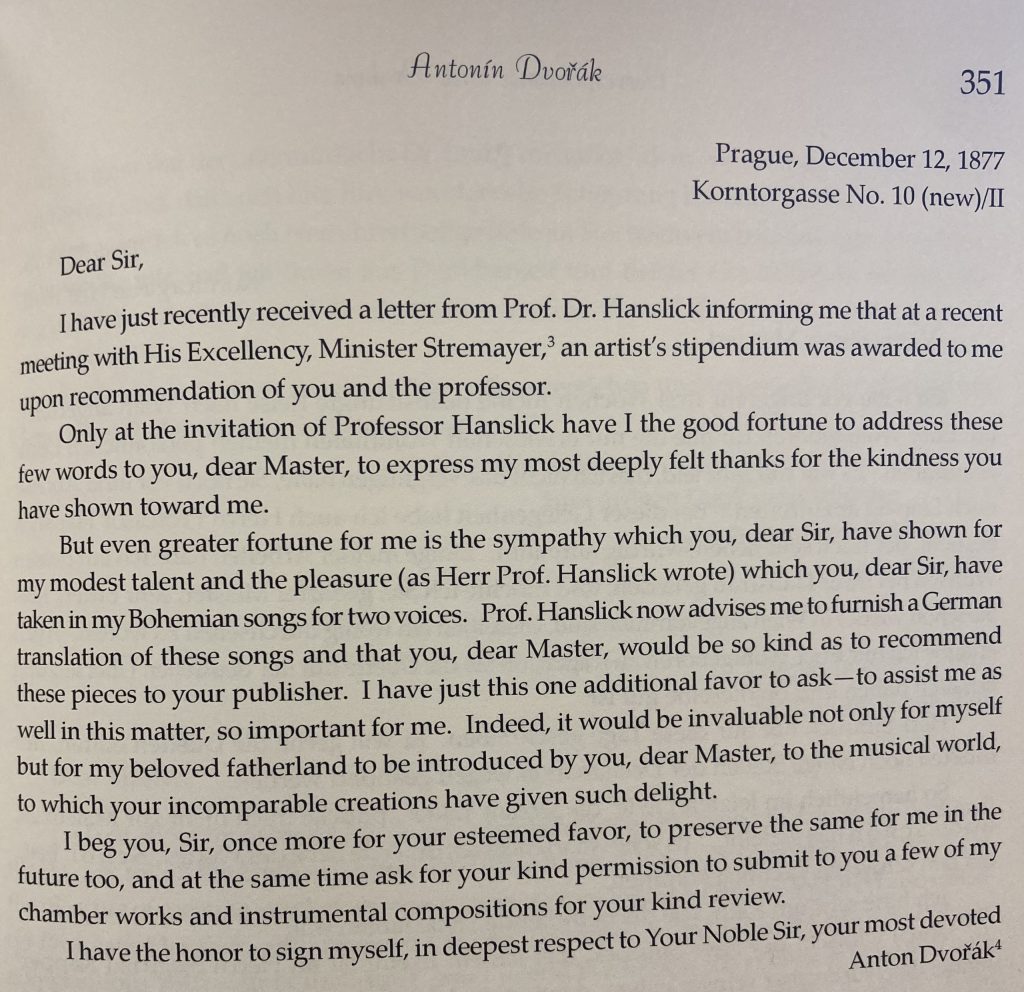

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)

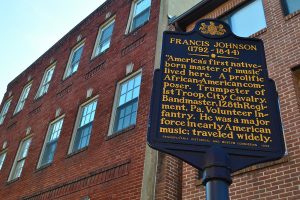

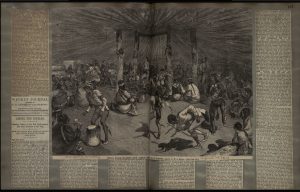

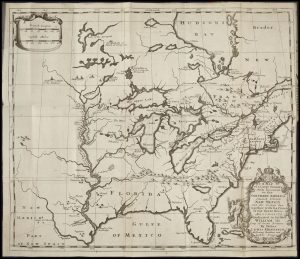

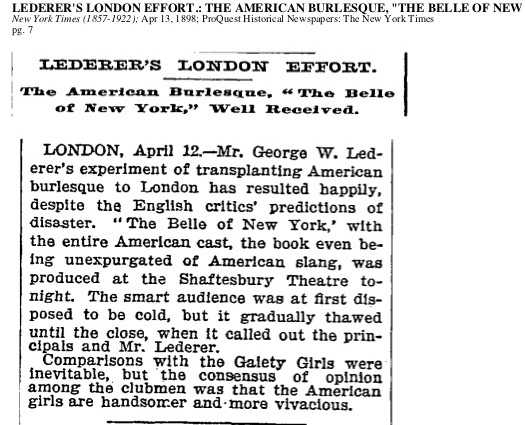

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

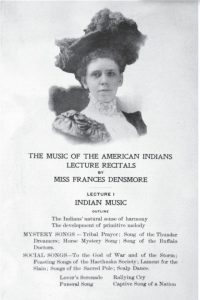

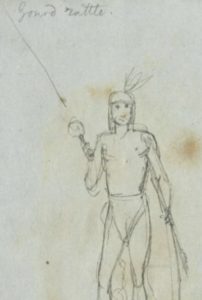

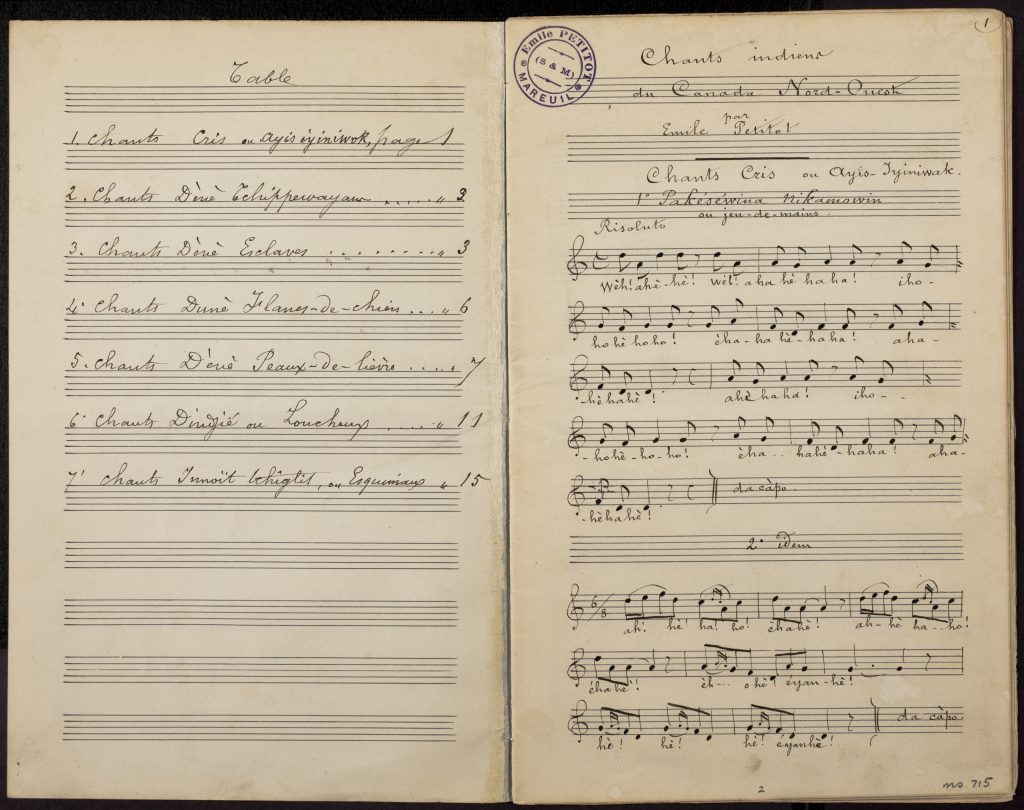

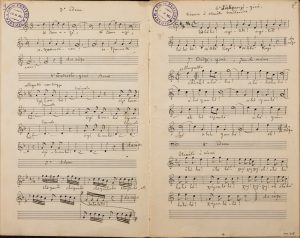

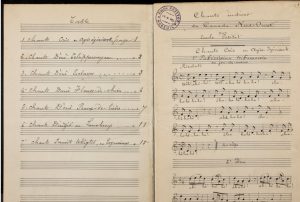

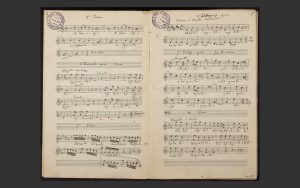

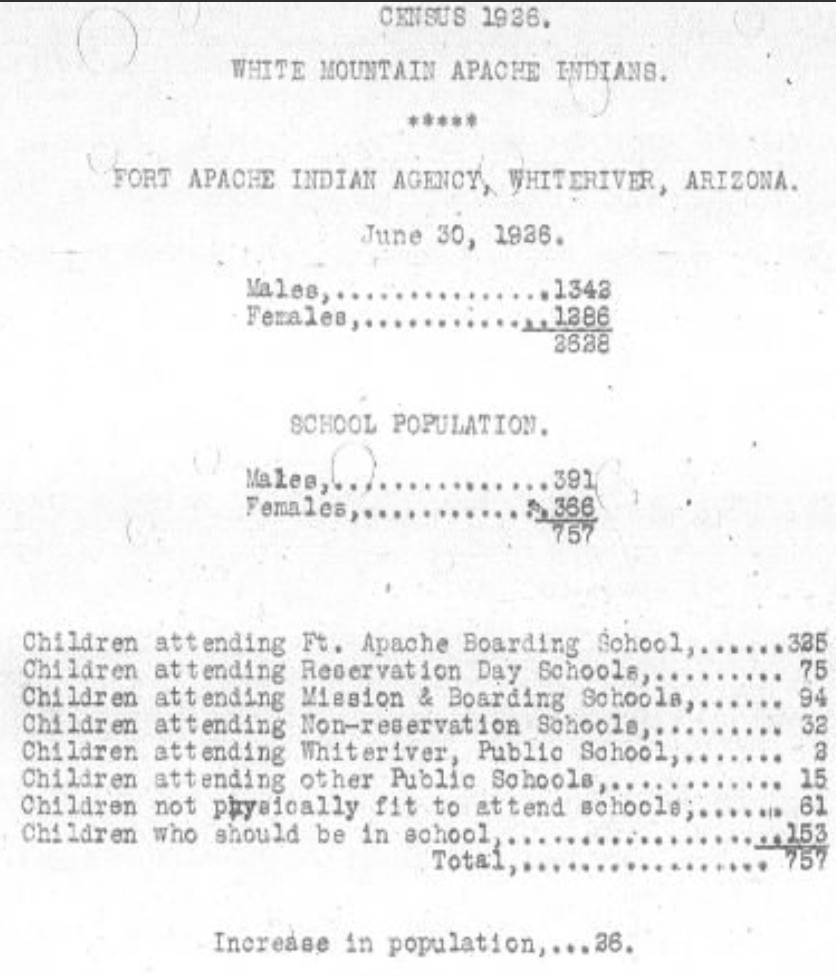

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in

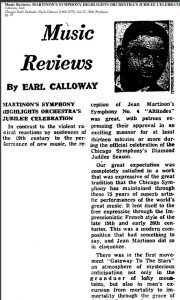

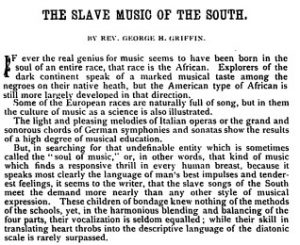

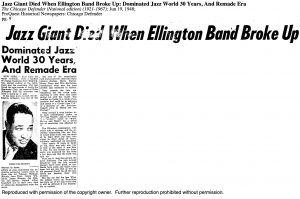

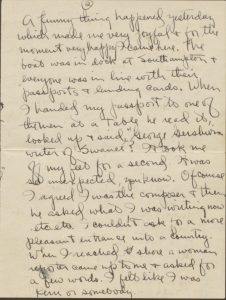

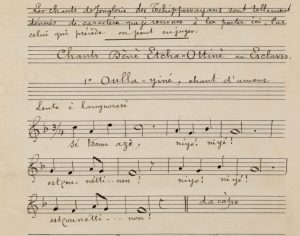

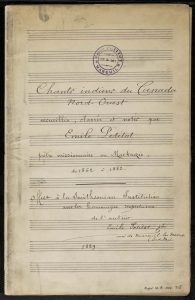

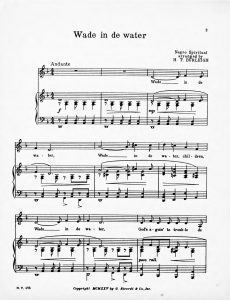

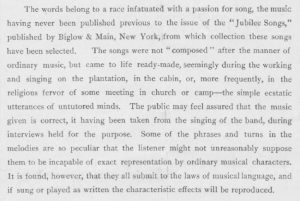

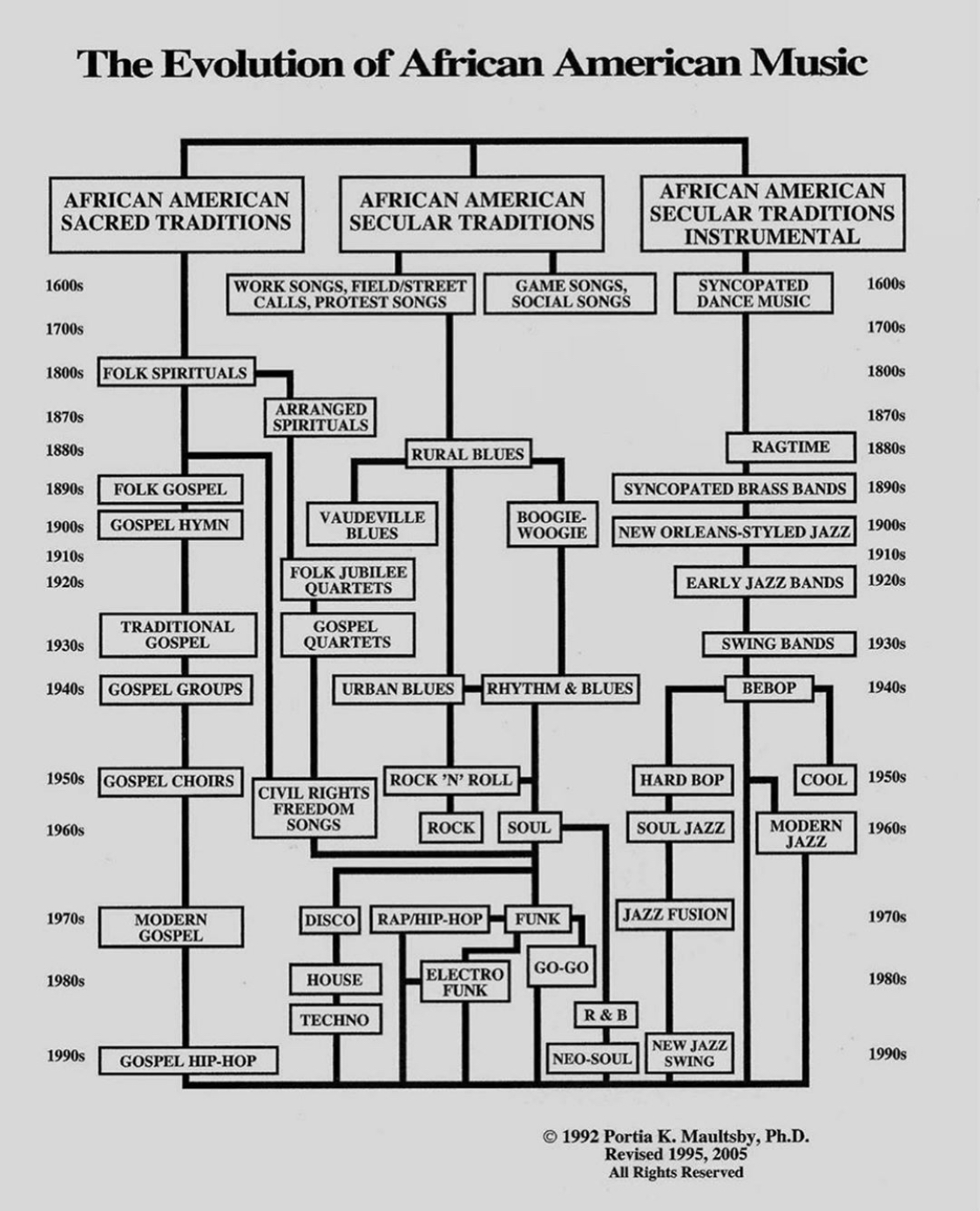

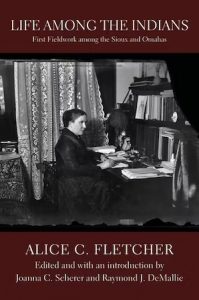

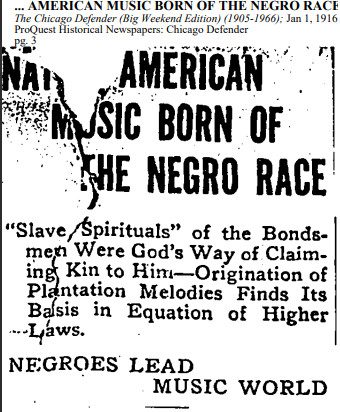

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.