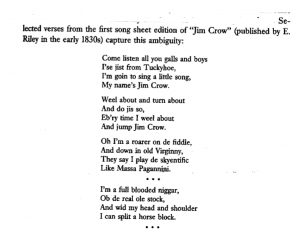

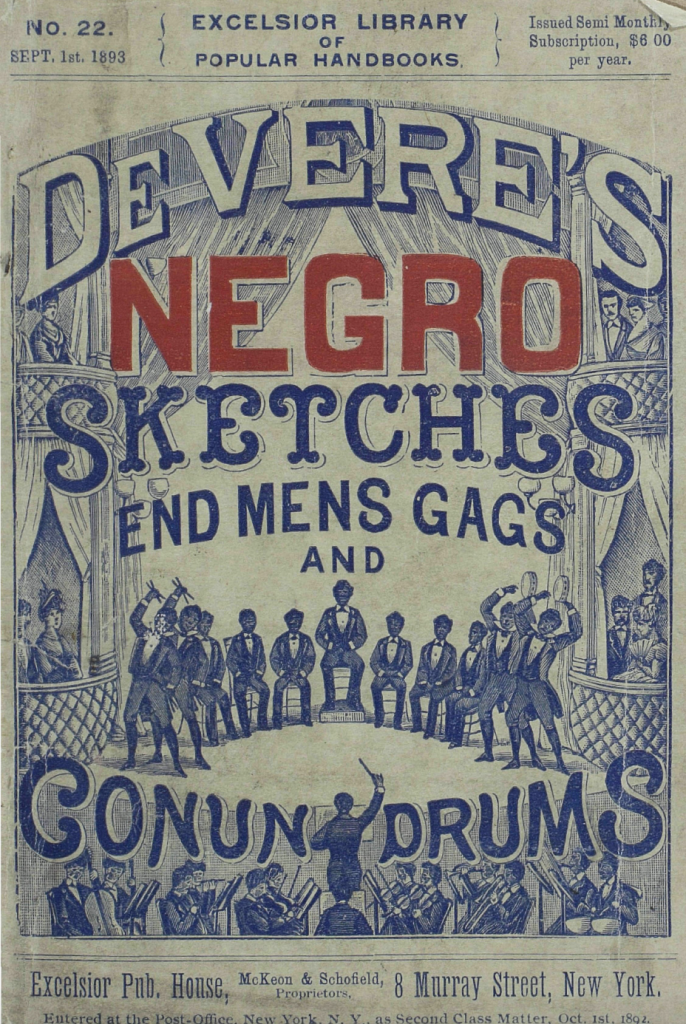

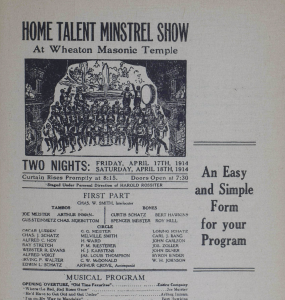

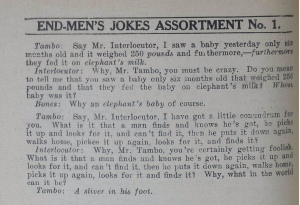

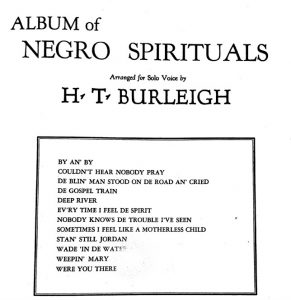

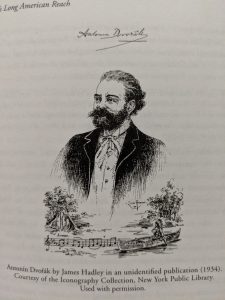

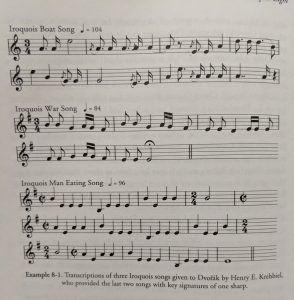

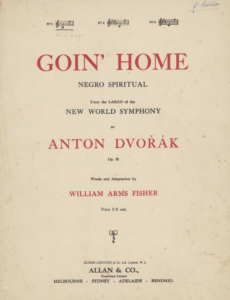

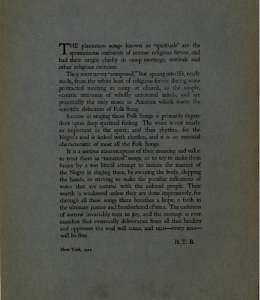

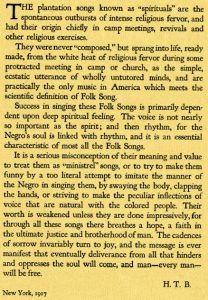

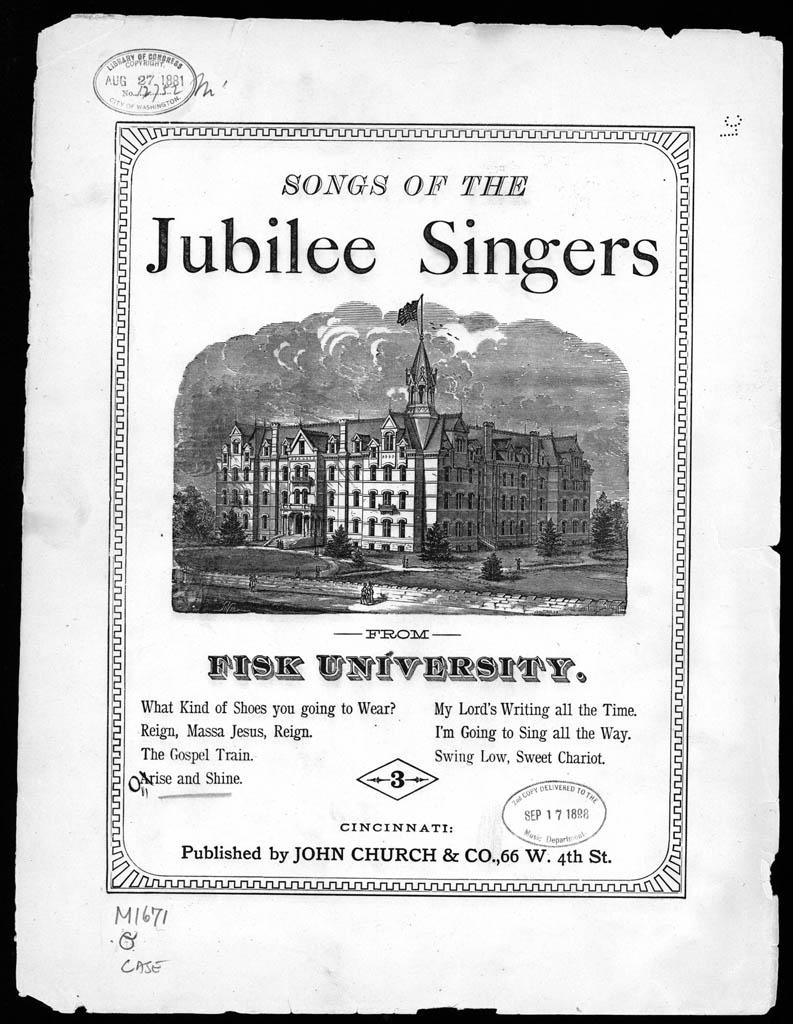

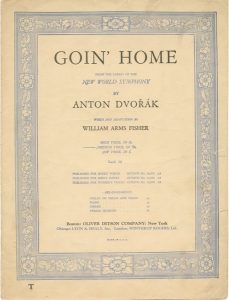

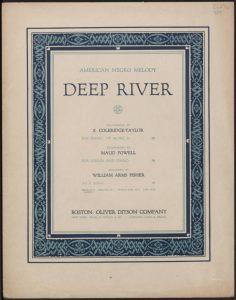

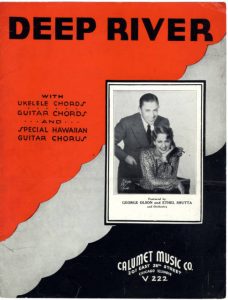

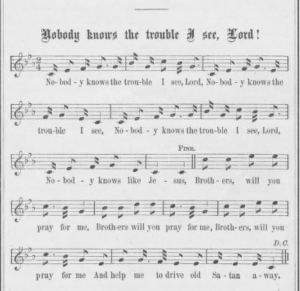

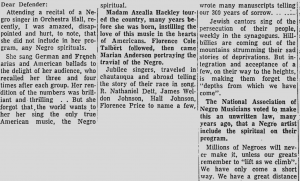

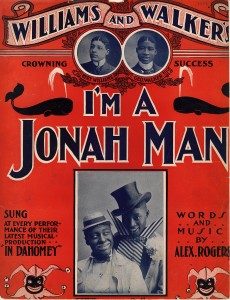

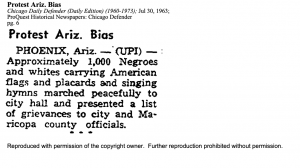

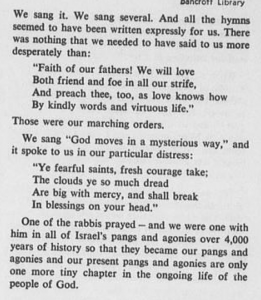

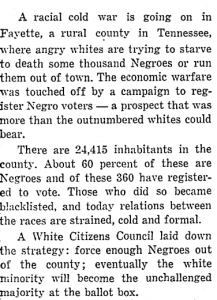

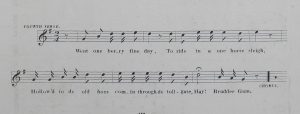

When I was working on the readings for our upcoming class, I was perplexed by the choices made in order to procure the definition of ‘American’ music. It just sounded to me like no one knew what they wanted, criticizing composers for sounding too European while accepting music from foreign enemies into the American cannon over those from marginalized groups of Americans. Fauser’s and Shadel’s articles do an especially good job in complicating the relationship between American music and European opinion, as the idea that American music must be differentiated in some way came from the Europeans and was put into practice first by Dvorak in his New World Symphony. This was so well received that it established the bohemian composer as an authority on African American spirituals, and many adaptations were made from his symphony to be marketed as authentic spirituals.

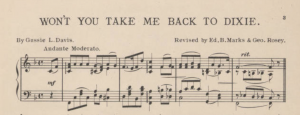

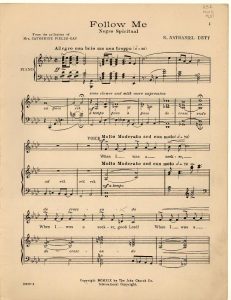

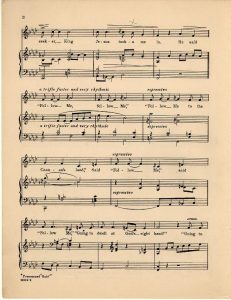

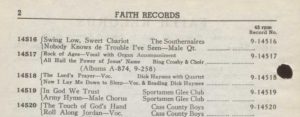

Goin’ Home: Negro Spiritual from the largo of the New World Symphony by Dvorak, Lyrics by Fisher

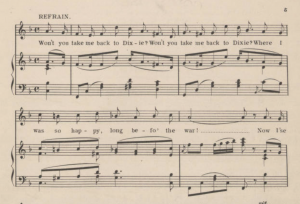

Down De Road: From the Largo of the New World Symphony by Dvorak, lyrics by Kagles

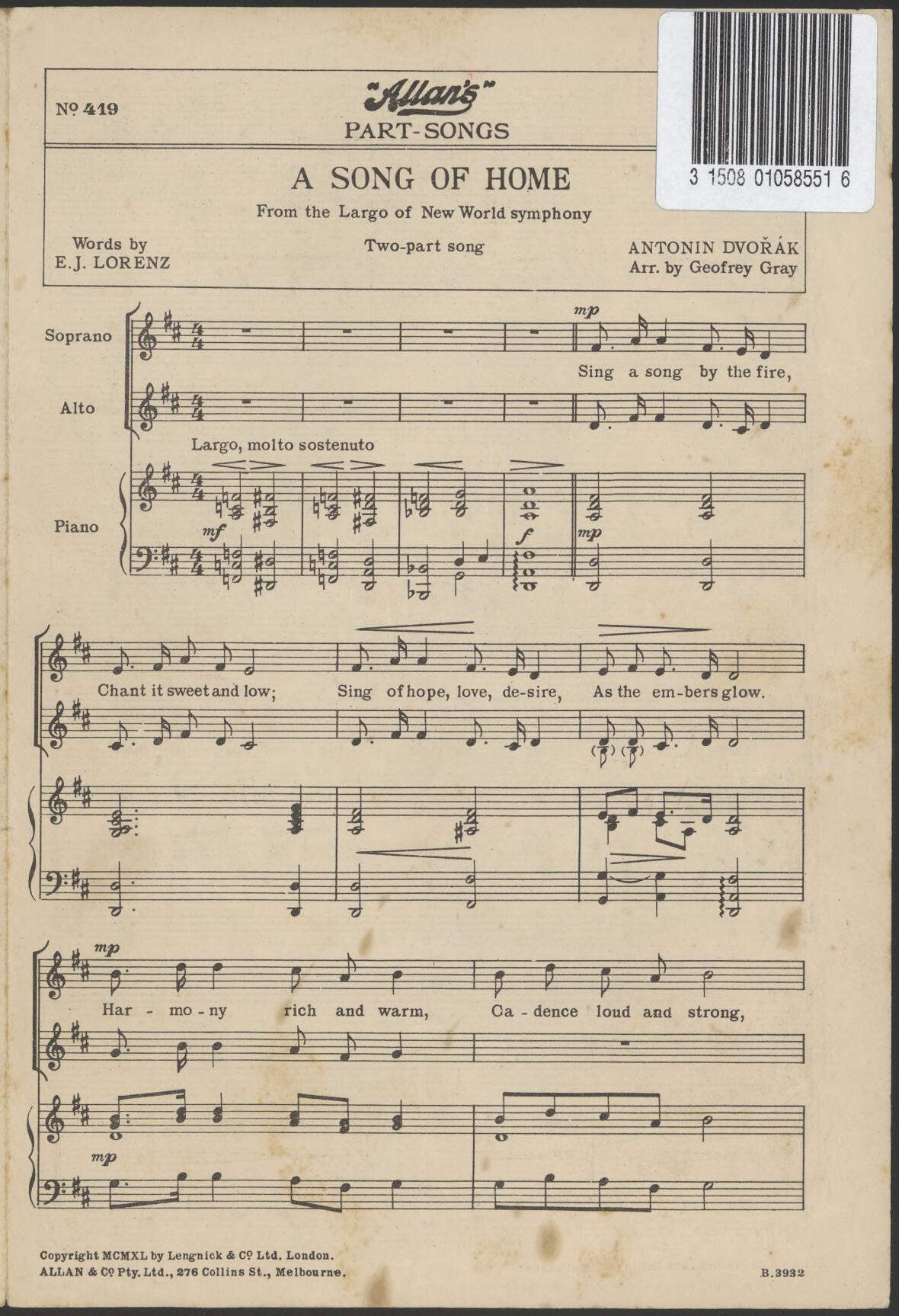

A Song of Home: From the Largo of the New World Symphony by Dvorak, Lyrics by Lorenz

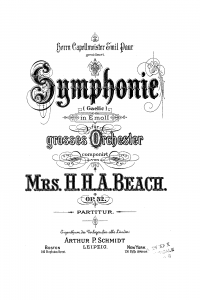

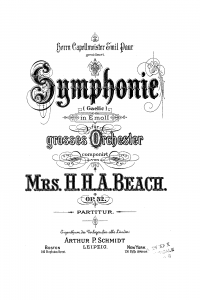

I was interested in the portion of Shadel’s article on Amy Beach’s response to Dvorak’s symphony and how she created her own interpretation. Having been born and raised in America, one would think that Beach would have a leg up on Dvorak in composing American symphonies. Her Gaelic Symphony, being the first symphony composed by an American woman, fits much of the criteria proposed of the idealized ‘great American symphony’. Meanwhile, Beach’s symphony was not taken seriously by critics due to her gender. Compared to Dvorak and Chadwick, Beach’s music was described by critics as “delicate”, “beautiful” and “tender”, while “other early reviewers… did not comment at any length on the expression of a national identity given the works clear dialogue with Dvorak” [1]. It was striking that many of the quotes, whether positive or negative, couldn’t help but mention Beach’s gender in relation to the music, while “the most negative critics displayed heightened anxiety over the emergence of a truly valid American symphonic voice capable of speaking to international audiences” [2]. This is what people had been hoping for in the ‘great American symphony’; however, for some, the fact that this voice was coming from a woman was the sole thing rendering the attempt invalid.

Beach Symphony in E Minor, Op. 32 ‘Gaelic’

Follow these links to listen for yourself:

Beach, Symphony in E Minor, Op. 32, “Gaelic Symphony”, I. Allegro con fuoco

Dvorak, Symphony No.9 in E minor, Op. 95, B. 178, “From the New World”, I. Adagio- Allegro molto

Chadwick, Symphony No. 3 in F Major, I. Allegro sostenuto

Chadwick purportedly told Beach after her symphony’s debut, “I always feel a thrill of pride myself whenever I hear a fine new work by any one of us, and as such you will have to be counted in, whether you will or not—one of the boys” [3].

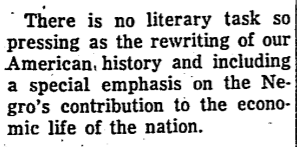

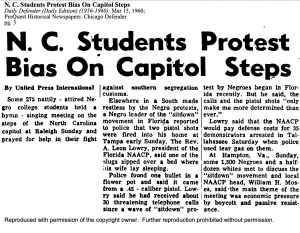

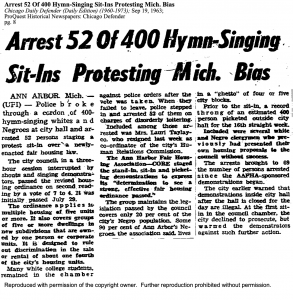

American music has a long history of discrimination on the basis of race, gender, class, etc. When we think about American music, we must also stop to think about who’s experiences we are validating and invalidating. Who are we letting participate and why? We cannot tout the idea of an American “melting pot” of musical culture if different groups are not all respected equally.

_____

- Shadle, Douglas W. Orchestrating the Nation : the Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- ibid

- Block, Adrienne Fried E. Douglas Bomberger. “Beach [née Cheney], Amy Marcy.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 16 Oct. 2019. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000002409.

Works Cited:

Beach, Symphony in E Minor, Op. 32, “Gaelic Symphony”

Block, Adrienne Fried E. Douglas Bomberger. “Beach [née Cheney], Amy Marcy.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 16 Oct. 2019. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000002409.

Chadwick, Symphony No. 3 in F Major

Dvorak, Symphony No.9 in E minor, Op. 95, B. 178, “From the New World”

Dvorak, Antonin and Fisher, William Arms. Goin’ home Negro spiritual from the largo of the New World Symphony, op. 95 Adelaide: Cawthornes Ltd, 1922. Web. 16 Oct. 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-166692271>

Dvorak, Anton and Klages, Raymond, “Down De Road : From The Largo Of The New World Symphony” (1925). Vocal Popular Sheet Music Collection. Score 4824.

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mmb-vp-copyright/4824

Dvorak, Antonin, Lorenz, E.J and Gray, Geofrey. A song of home from the Largo of New world symphony : two-part song Melbourne: Allan & Co, 1940. Web. 16 Oct. 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-170769555>

Fauser, Annegret. Sounds of War : Music in the United States During World War II New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Shadle, Douglas W. Orchestrating the Nation : the Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

“Naxos Music Library – Invaluable Resource for Music Enthusiasts and Collectors.” Naxos Music Library – Invaluable Resource for Music Enthusiasts and Collectors, https://www.naxosmusiclibrary.com/.

showing they take priority before any other group even though there are more participants in other ensembles within the massed choir, like Chapel Choir.

showing they take priority before any other group even though there are more participants in other ensembles within the massed choir, like Chapel Choir.

[2]

[2]