On May 7th 1921 The Chicago Defender published an article titled “BLACK SWAN RECORDS, new corporation announces first list of productions – Fills Long Felt Want.” Along with the written ad the following illustration was included in that same issue.

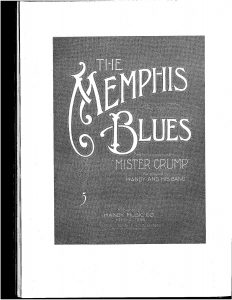

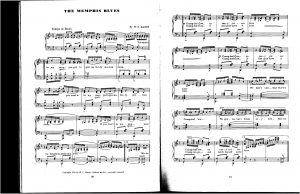

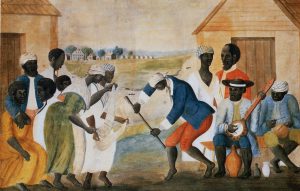

Black Swan Records was founded in 1921 by Harry Pace and W.C Handy. Based in Harlem, NY it was the first African American owned and operated record label in the United States. The company was formed with the explicit intention of creating music by and for African American consumers. Its first records included recordings of art songs sung by revella Hughes and blues sung by Katie Crippen.

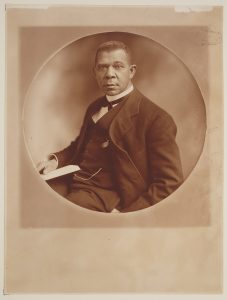

The choice by Pace to record art songs was a philosophical choice. Pace met W.E.B Du Bois during his time at Atlanta University. Du Bois’ thought was incredibly influential on Pace throughout his life. Crucial to this was Du Bois’ idea of the ‘talented tenth,’ the idea that an elite 10 percent of the race produce the vast majority of the accomplishments and would be able to uplift the bottom 90% through their efforts. Our modern criticism of this idea aside it is clear that Harry Pace identified with Du Bois and his ideas very closely. His choice to record art songs on the first records was a purposeful attempt at respectability politics of the time.

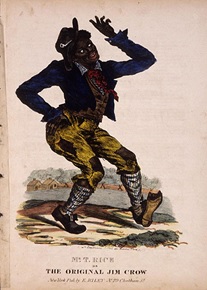

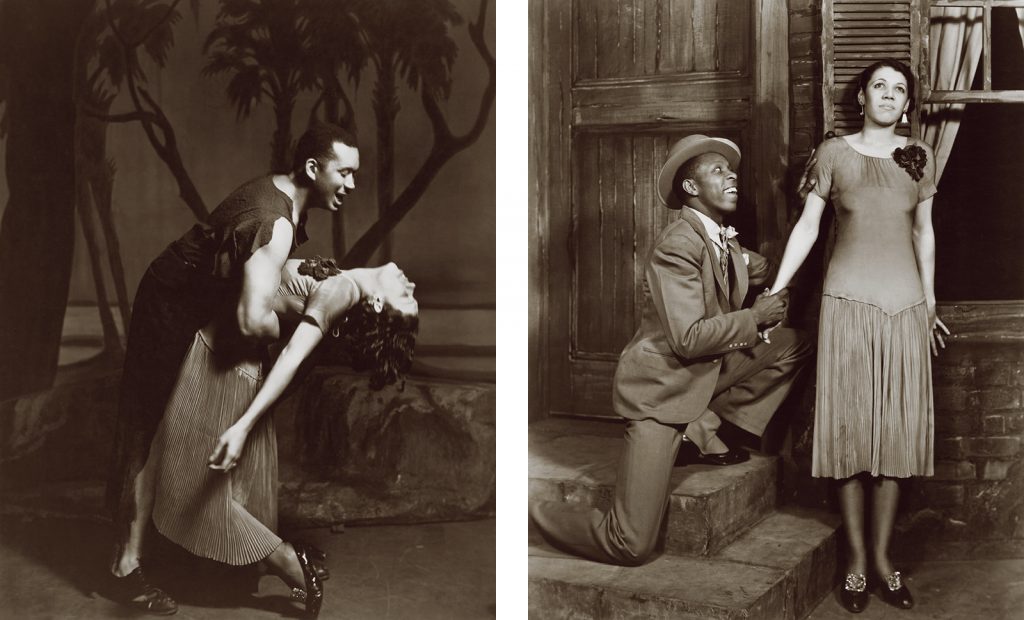

It was not, however, the art songs that would bring commercial success to the label. That would Be Ethel Waters with her record “Down Home Blues.” So called ‘hot’ records were not the goal of the company but would ultimately prove to be its savior when Ethel Waters went on a tour of southern cities with the “Black Swan Troubadours” in 1921. Unfortunately, the good times would not roll and Black Swan could not keep up with the increasing amount of records of black artists put out by larger white labels such as Paramount and Columbia. The Label declared bankruptcy in December of 1923 and was bought by Paramount by March of 1924.

Black Swan Records had a relatively short existence of about 3 years. Despite that small amount of time the impact the label had on recordings of African American music was incredible. Without this record company it would have taken much longer for the larger white labels to realize the commercial opportunity that was available.

I highly recommend the podcast series “The Vanishing of Harry Pace.” It goes much deeper into the story of Black Swan Records and Harry Pace as an individual.

Bibliography

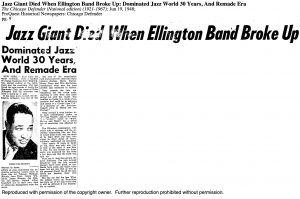

“BLACK SWAN RECORDS: NEW CORPORATION ANNOUNCES FIRST LIST OF PRODUCTIONS–FILLS LONG FELT WANT.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), May 07, 1921. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/black-swan-records/docview/491888074/se-2.

“Display Ad 27 — no Title.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), May 07, 1921. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/display-ad-27-no-title/docview/491880278/se-2.

Gilles, Nellie. “Radio Diaries: Harry Pace And The Rise And Fall Of Black Swan Records.” NPR, July 1, 2021, sec. The Sounds of American Culture. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/30/1011901555/radio-diaries-harry-pace-and-the-rise-and-fall-of-black-swan-records.

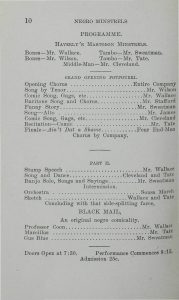

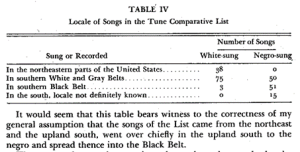

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]