There are often trends throughout history that seem to take on a timeless role. In this instance, I am talking about colonialism. Whether it is researching about the cultural intersect of “New Spain” from in the 16th-18th centuries to the seemingly harmless independence of Cuba from Spanish rule- music always seems to do a superb job in representing ideologies and themes of the times that they were written in.

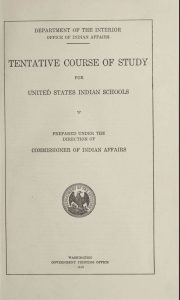

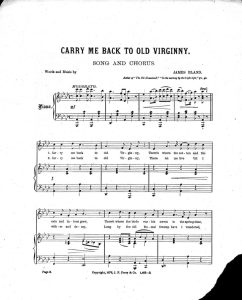

It turns out- after a deeper dive into the primary source I found (to my knowledge, for the very first time), I realized that this was the same exact source I used for my first blog post! I was deceived by the different cover, formatting, and last but not least- the mYstEriOusLy changed title. Do I have an explanation for this? No. But was I completely flabbergasted? You bet! This title cover was the first one that I looked into. I, at the time, could not find the music to this piece.1

Chas M. Hattersley, “Patriotic American Sheet Music.” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience

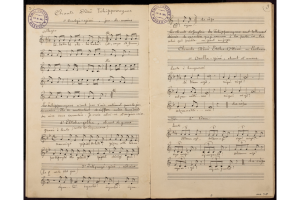

To my surprise, this time around- I found not only the music to this piece but also a different printed version of it.2

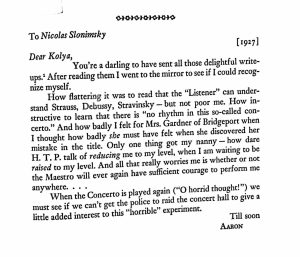

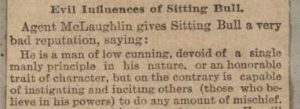

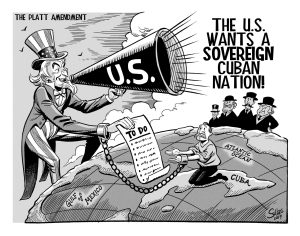

Same composer and same lyrics- but different enough for a college music student to almost get stumped by two seemingly different songs. The difference in the title really caught my attention. In looking at the cover that says, “Free Cuba” in all caps, I, in my naive-ness, thought that this song seemed pretty harmless, looking through the words and realizing that this was America’s cry for Cuba’s freedom. A cry out of support and sympathy. But I found myself completely wrong when I looked more into the history of this song and what it pictured amidst the Spanish-American war. This was not a war to gain Cuba’s independence. This war was to transfer rule from one colonist country to the next. This song represents what the “Cuban independence” really meant to America, which can be summarized through the Platt Amendment3 that was enacted in 1901, essentially kept Cuba under the restrictive power of the United States.

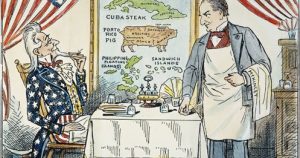

W. McKINLEY CARTOON, c1900. American cartoon comment, c1900, on Uncle Sam’s seemingly insatiable imperialist appetite; waiting to take the order, at right, is President William McKinley.

Cartoon regarding the Platt Amendment: “The U.S. did not want the Spanish-American War to be seen as an imperialistic land grab for Cuba.” (https://apprend.io/apush/period-7/platt-amendment/)

This song pictures the triumph that would take place for America, being able to take over what was another territory.

The representation of various historical events seen through music, as seen through my trial and error, has to be carefully examined and researched. There is no glossing over history and the colonial underlying themes that seem to bleed through history.

1 “Patriotic American Sheet Music.” In The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2021. Image. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1470303.

2 Hattersley, Chas. M. Free Cuba; or, Uncle Sam to Spain. Pond & Co., Wm. A., New York, monographic, 1873. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1873.15560/.

3 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Platt Amendment.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 24, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Platt-Amendment.

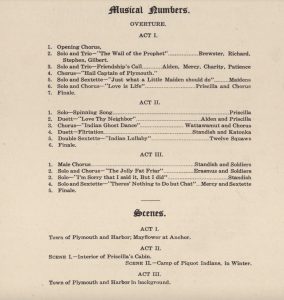

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.