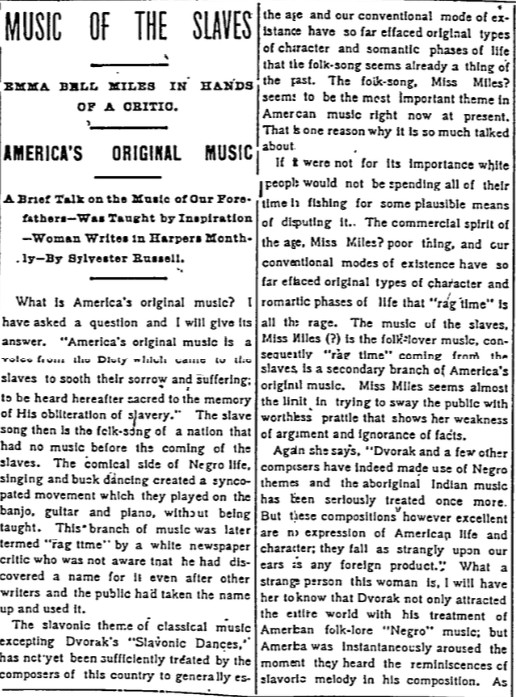

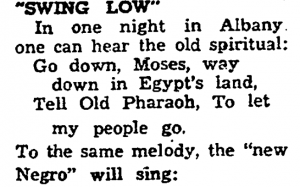

Often when we think of Appalachian music, we envision a white man sitting on his porch playing a banjo. In class we’ve discussed the commercial nature of this narrative that exists in our culture, as well as the work of Rhiannon Giddens, who has worked to counter these generalizations and lack of knowledge about the African American origins of bluegrass music from the Appalachian region. Sophia Enriquez, a professor and musicologist at Duke University, studies Latinx music in the Appalachian region and takes a deeper dive into the culture of music from the American south.

As Appalachian folk music had been established and country began emerging as a popularized genre, Enriquez reminds us that Mexican ranchera music and country music did not develop independently of one another. The 1930s served as “The Golden Age” in Mexico, where cultural products such as movies and music began to define Mexican culture. This is reflected in the development of both ranchera music in Mexico and country music in the United States. The Carter Family is an emblematic example of the important mix of influences that constructed today’s Appalachian and country music, as well as Mexican ranchera and tejano music. The Carter Family, remembered for having helped develop the country canon, moved to Del Rio Texas in 1938 where their music was broadcasted twice a week by Mexican radio station XET, their music being consumed by both spanish and english speaking audiences.

I invite you to listen to the following two clips, comparing the musicality of these two songs that were released in the 1930s:

Latinx, especially Mexican migration to the U.S. sky-rocketed in the 1940s and 50s with Word War II, with migrant workers moving to agricultural areas such as North Carolina and Virginia. With this blend of cultures, there was inevitably a mix of musical influences that shaped these two genres during the peak of their popularization.

Groups today, such as Lua Project based in Virginia, seek to commemorate and raise awareness for this cultural integration that has occurred across generations. They intentionally represent this through the blend of Mexican ranchera and Appalachian style and instrumentation. Take a listen below:

As we discuss American music and what it means for us today, it is important to critically consider all of the complexities that construct our musical traditions, and what communities we need to shift our attention towards in order to envelop all of the historical narratives that exist in our American history.

Enriquez, Sophia M., and Danielle Fosler-Lussier. “Canciones de Los Apalaches: Latinx Music, Migration, and Belonging in Appalachia.” Canciones de Los Apalaches: Latinx Music, Migration, and Belonging in Appalachia, Ohio State University, 2021.