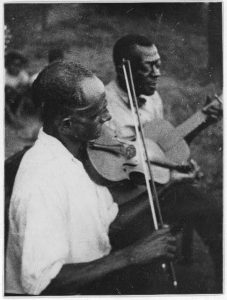

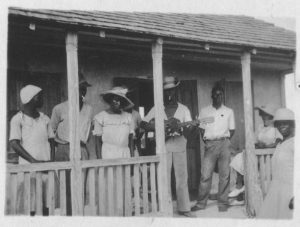

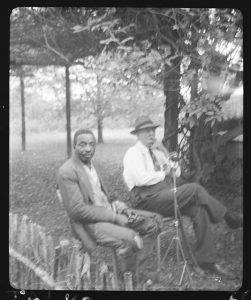

What caught my eye whilst perusing the Lomax archive was this photograph:

The men depicted are both in prison uniforms, and on the back of the photograph is handwritten, “poss. Leadbelly”; Angola, Louisiana, July, 1934; “Huddie Leadbetter”.

I guess I wasn’t the first to be captured by this image because when I googled the description, the Lomax collection, of course, came up; what I didn’t expect to see was an Amazon link that resold reprints of the image. Further investigation led me to not just one, but several documentaries surrounding the culture of the Angola Prison (AKA: The Louisiana State Pen). Angola is currently the largest maximum-security prison in the United States and resides on 18,000 acres of property [1]. The land which was a plantation pre-civil war was “transformed” into a privately-owned prison by a former confederate general in the late 19th century where slave labor was replaced by inmate labor[1]. Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly) was in a way discovered by Alan Lomax while collecting in the south and aiding Lead Belly in recording an album, helped to secure his early release by sharing the album with Louisiana Governor O.K. Alan [2].

Whether or not the inmate in the photo is Heddie Ledbetter is unclear, however, the photograph provides evidence that musicking did not stop once people were convicted.

I have a few questions in regards to the motives of the Lomaxs that include: Why did the Lomaxes decide to collect from prisons? Did it have to do with concepts of the authenticity of black music? Similarly, how did Jim Crow Era politics and criminal justice have to do with the perpetuation of black musicks? Josep Pedro’s biography on Leadbelly suggests that there was indeed a power dynamic at play.

“Leadbelly was effectively liberated in 1934 and the popular legend – backed by both the Lomaxes and the artist himself – made the white ‘ballad hunters’ responsible for the black man’s liberation.” [4]

https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/leadbelly/cite?context=channel:march-of-time-y6

The Lomaxes created a short film surrounding the liberation of Leadbelly and his transformation into a blues star. The video feels rehearsed (Leadbelly stumbles over a line at 2:28) and is shot skillfully with the usage of continuity editing and non-diegetic noise. Lastly, the film declares the Lomax discovery of Leadbelly’s music was, “the greatest folk song find in 25 years” [3]. The physical copies of his music were then to be stored in the same archive as the original copy of the Declaration of Independence [3]. The juxtaposition of the two is certainly evoking and ethos in legitimizing Leadbelly’s music as authentically American.

Works Cited

[1] Schrift, Melissa. “Angola Prison Art: Captivity, Creativity, and Consumerism.” The Journal of American Folklore 119, no. 473 (July 1, 2006): 257–274.

[2] “Leadbelly.” In Chambers Biographical Dictionary, by Liam Rodger, and Joan Bakewell. 9th ed. Chambers Harrap, 2011. https://ezproxy.stolaf.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/chambbd/leadbelly/0?institutionId=4959

[3] March of Time. Volume 1, Episode 2. “Leadbelly”. [New York, NY] Home Box Office, 1935. Accessed September 26, 2019. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/leadbelly.

[4] Pedro, Josep. “Leadbelly.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Singer-Songwriter, 111–119. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

![[Members of the Bog Trotters Band, posed holding their instruments, Galax, Va. Back row: Uncle Alex Dunford, fiddle; Fields Ward, guitar; Wade Ward, banjo. Front row: Crockett Ward, fiddle; Doc Davis, autoharp]](https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsc/00400/00401r.jpg)

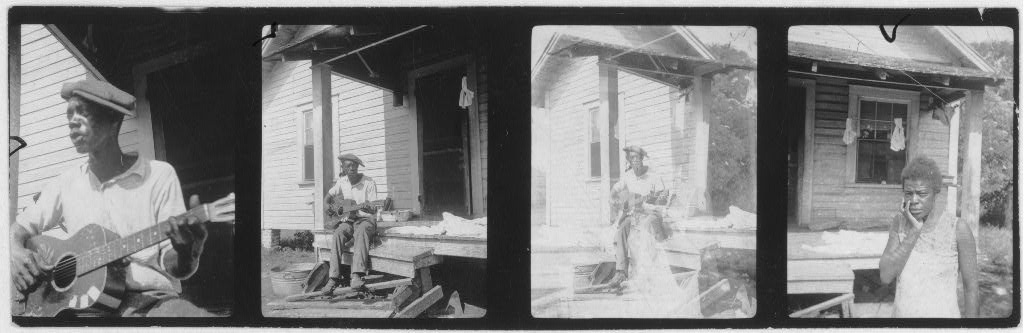

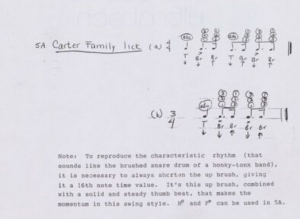

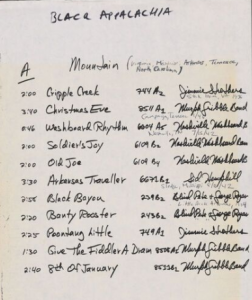

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song,

woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song,

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]