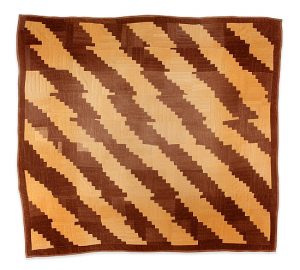

Exploring the Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) website, the colorful patterning and geometric shapes of the “African American Quilts” tab caught my attention. Without an initial intention of exploring the quilting page because there wasn’t an obvious connection to music, it came to my surprise when the first sentence of the collection description was a quote by Nettie Young:

‘Quilting is mostly like singing’

Nettie Young (1916-2010), a quiltmaker previously associated with Gee’s Bend quilting collective, created beautiful quilts from a young age to adulthood. Her quilts have been displayed and collected in museums such as the New Orleans Museum of Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In her “About” page, Young describes her experience in quilting, how she came to learn about the artform by watching her mother take scraps of fabric and sew the fabric to create a larger piece of cloth, eventually forming it into a functional quilt. Young shares that whatever she saw, she could sew, and there was no need for her to use patterns:

“If I seen a dress or a quilt or something I liked,

I can make it. I just draw it out the way I want it.”

She pointedly states that the use of patterns in her sewing inhibited her creativity. I think it’s interesting to note that this way of learning and doing an art form seems freeform – Young reached into her mind’s eye to create clothing, quilts, art pieces from bits of fabric, and learned how to do so through, initially from what we know, observation and experience. This is similar to stories of musicians such as Louis Armstrong, who grew up initially exposed to music through his community and practitioners of jazz, to then growing up to become an incredible influence to jazz by effectively tweaking the way jazz was recorded and performed.

Fig. 1. “The Bricklayer”, “one of Nettie’s favorite quilt patterns” (Wikipedia, 2024)

Fueling my curiosity to seek a connection between music and quilting, I launched into a search on other databases and webpages to find audio recordings of quilting sessions; perhaps we’d hear some of the songs that are alluded to in the ACM African American Quilts description. In recordings about quilting on the Library of Congress, many quilters discussed the techniques or their experiences in quilting, and a few interviews discussed the experience of quilting in groups. In an interview with Fannie Lee Teals in Tifton, Georgia, she briefly mentions her mother singing while quilting when she first began to learn of the practice (19:00) :

‘Since I was a kid. I always would pay attention to anything

my mother would do. I would even pay attention to her songs,

you know, she would sing.”

Through this interview, we see again how quilting is cultural knowledge, passed down through observation from a young age, and additionally, we see that music is also, in some way, connected to quilting. Chris Clark, whose work such as The Saxophone Player and Grandma, is also featured in ACM’s African American Quilts exhibition, is another example of learning quilting through family, as he learned to quilt from his grandmother at the age of 33.

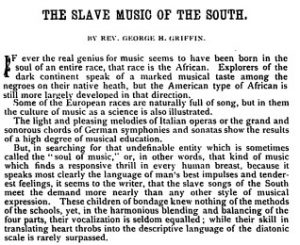

Not able to successfully find recording sessions of group quilting sessions that featured the quilters singing or engaging in music, I opted to learn more about quilting, which seemed to be a tradition and practice handed down through family or community knowledge, much like how spirituals and hymns were passed down generation to generation orally. Exploring the History of African American Quilting, explores how quilting is embedded in African American history, particularly focusing on “Gee’s Bend” (officially known as Boykin), Alabama. Gee’s Bend was largely an isolated, small town where, the video claims, quilting initially took off in the US, beginning with the necessity and the practicality of creating quilts (providing warmth and as coded signs for enslaved people on the run), and eventually evolving to creating art pieces to display to fuel economic growth.

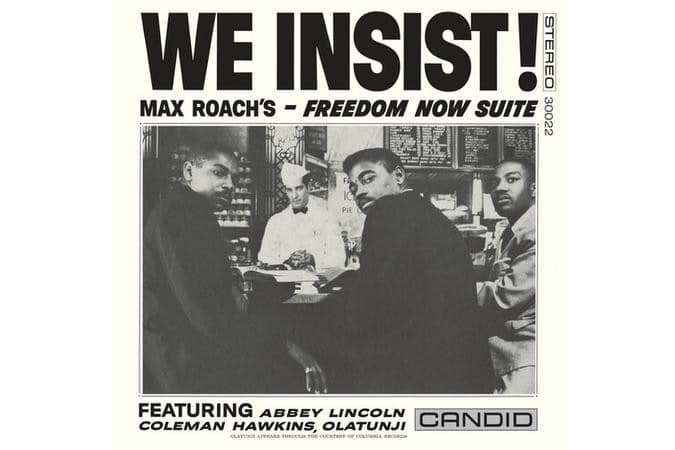

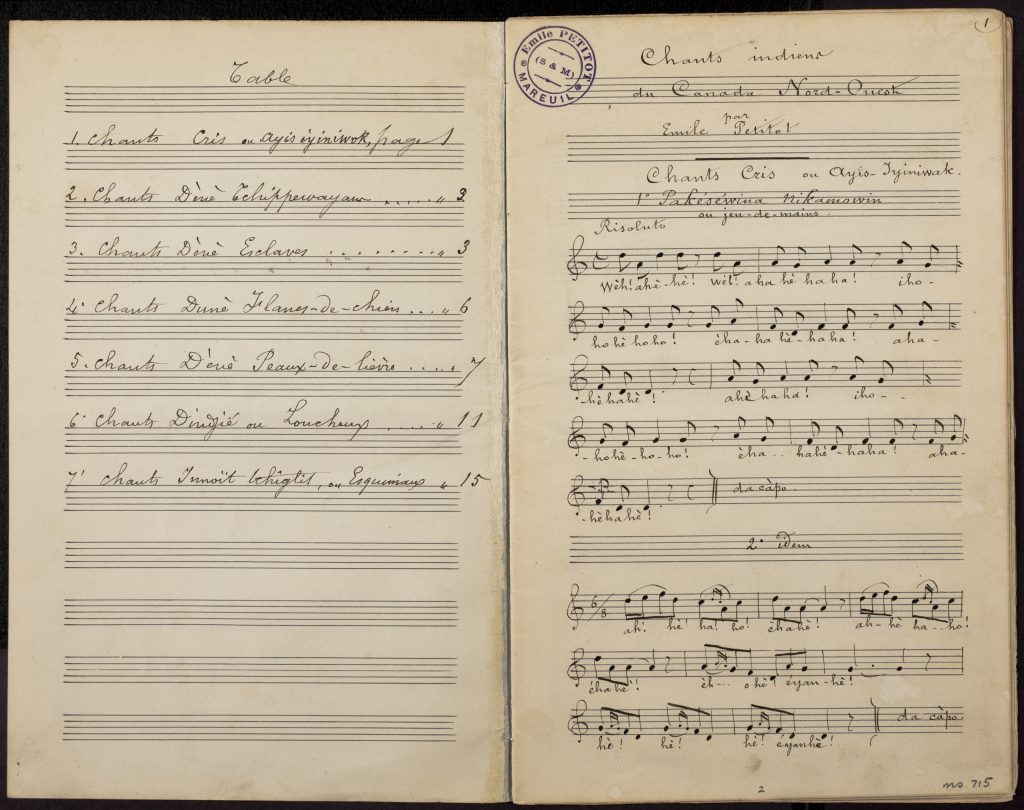

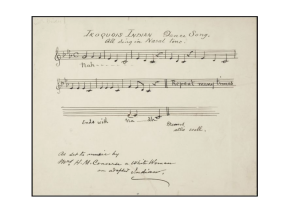

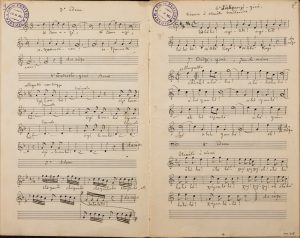

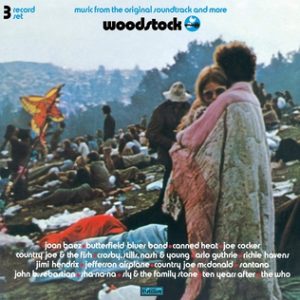

Wanting to explore the history of Gee’s Bend more as it seemed to be a central place of quilting in African American quilting history, I found Gee’s Bend Quilters’ Boykin, Alabama: Sacred Spirituals of Gee’s Bend, an album of spirituals sung by quilters and residents of Gee’s Bend, Mary Ann Pettway, China Pettway, Larine Pettway, and Nancy Pettway. These recordings may give us a glimpse into the music that may have been sung by African American quilters in community quilting sessions. They have also worked on or had their voices used in Jaimeo Brown’s self-named, avant-garde jazz album Jaimeo Brown Transcendence – Work Songs, fusing multiple musical forms: jazz, slave songs, work songs, Indian classical singing, country rock (?).

Though my search for quilting recording sessions was limited, I stumbled upon a documentary trailer of The Quilt, which uses quilting as an analogy to understand how African American music (such as jazz, the blues, gospel) in the US has transformed and built on one another throughout history.

It’s clear that, like Black American music, quilting has a history and place in Black cultural history. The practices of music and sewing played a significant role in individuals and communities before and after the emancipation of enslaved people in the US. As both practices have been passed down from generation to generation, the reasons for creating music and quilts, as well as what their end products look and sound like, have evolved.

Works Cited

“Nettie Young.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. last updated September 16, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nettie_Young

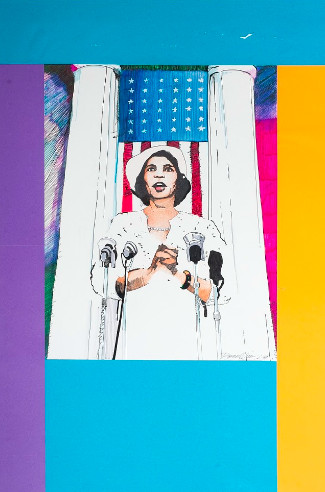

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)