First Ever Album Cover by Alex Steinweiss (1938) https://illustrationchronicles.com/alex-steinweiss-and-the-world-s-first-record-cover

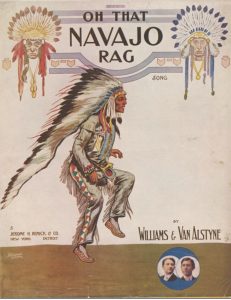

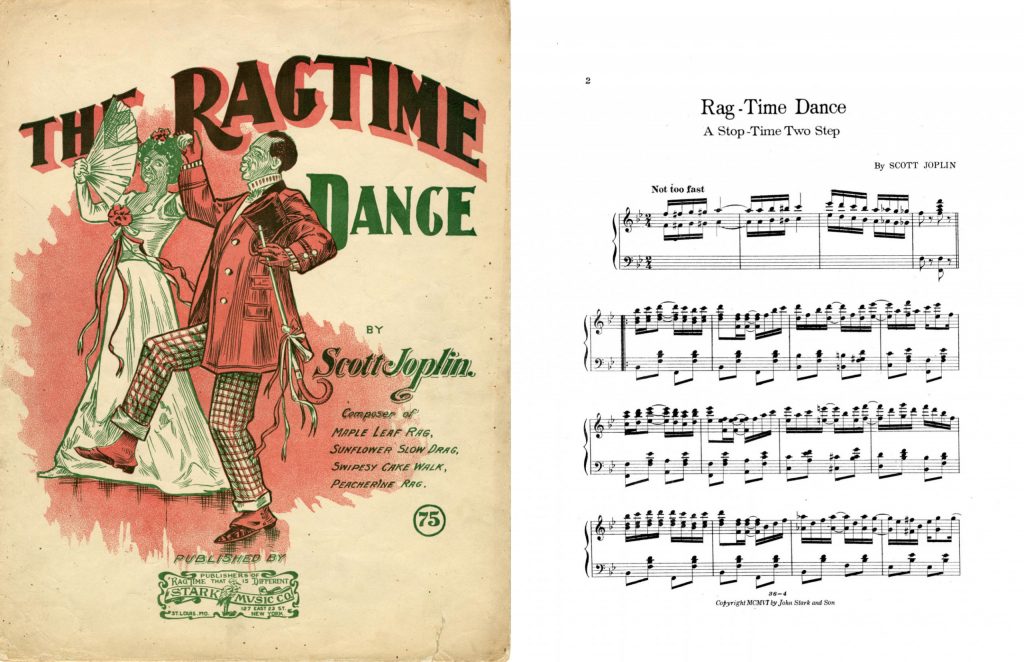

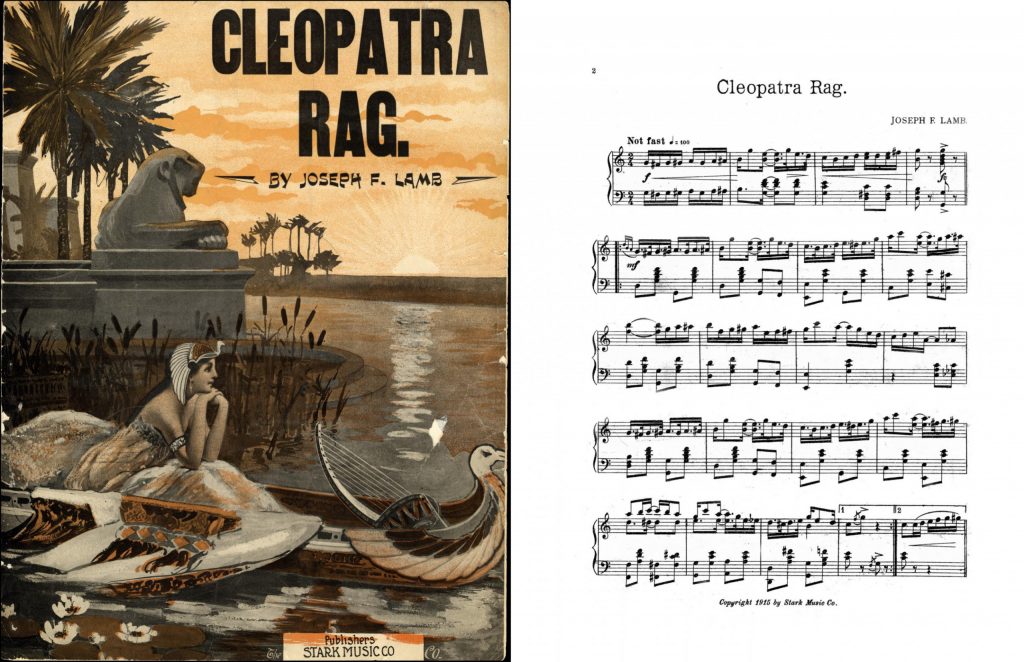

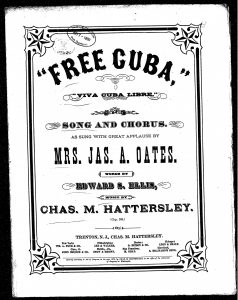

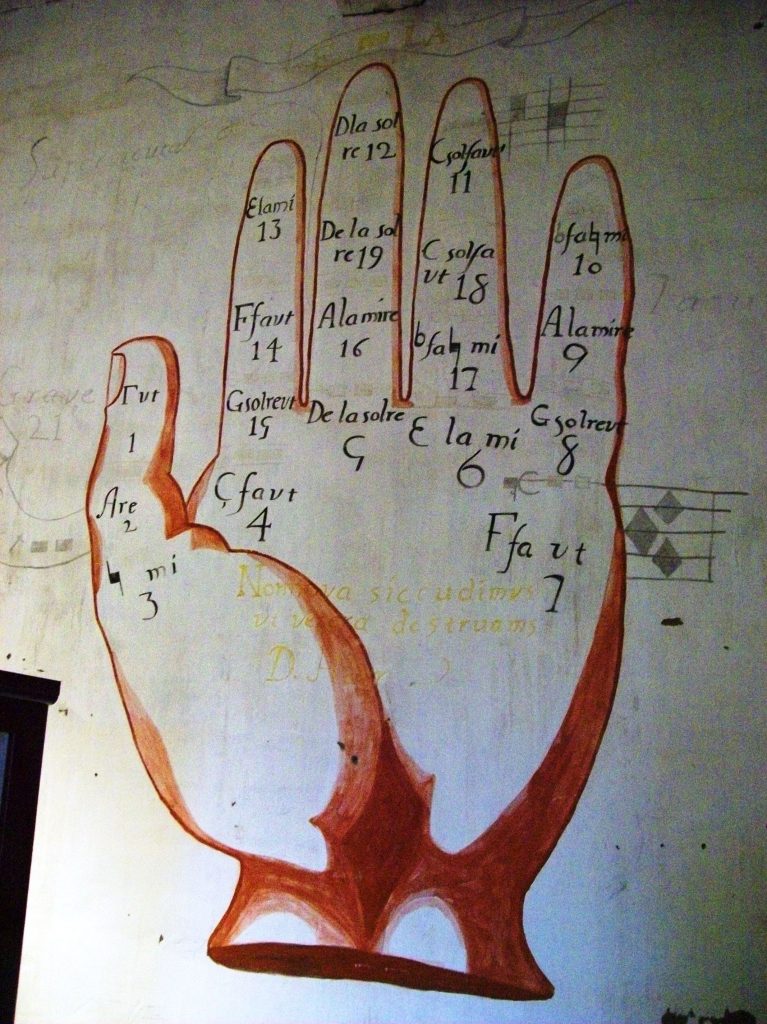

If you’ve ever seen an album cover, you might have an idea of what can commonly be found on the front page of musical scores. These score covers use visual elements to package and advertise music, often with elaborate illustrations that drew in prospective performers to the part. Score cover art for Native-American-influenced popular music (which unfortunately is more often than not inaccurately appropriated by white composers and/or artists with no indigenous backgrounds) provides an interesting insight into how Native Americans were perceived in 19th- and 20th-century America. Two common themes that I noticed in examining these score covers is the narrative of the Native American as primitive soldiers and on the contrary, as love interests.

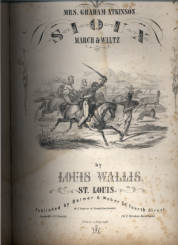

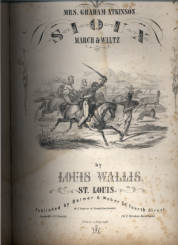

Sioux March & Waltz—Louis Wallis https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sheetmusic/id/23812

The cover art for Louis Wallis’ “Sioux Waltz & March” (1856) shows “A man on horseback in uniform is about to cut down with his saber a Native American he is chasing. Behind him, another of his comrades, at whom the Native American is aiming a bow and drawn arrow, is about to shoot the Native American with his pistol. A battle rages in the background, with Native Americans and soldiers visible,” (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). The simultaneous use of the Native American’s bow and arrow and the white man with a pistol reflects the 19th-century attitude that Native Americans were less developed in technology and other aspects of life than that in Western civilization.

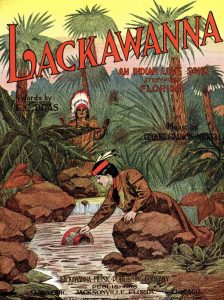

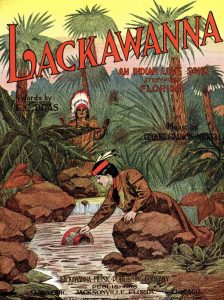

“Lackawanna: An Indian Love Song Story in Florida” by Eugene Francis Mickell (1912) https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ShtMus/id/13

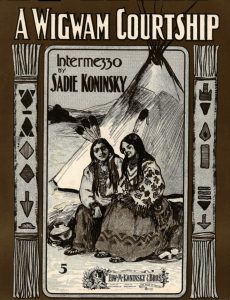

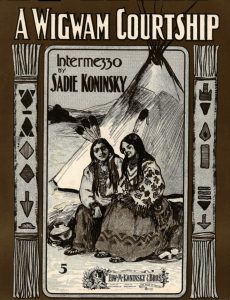

“A Wigwam Courtship; Intermezzo” by Sadie Koninsky (1903) https://repository.duke.edu/dc/hasm/b0229

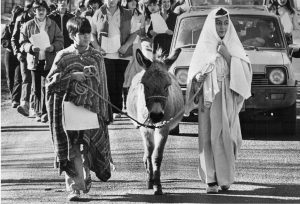

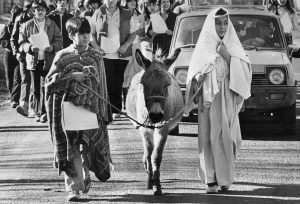

Another interesting theme in score cover art for Native American-inspired music is the fetishization of both relationships between two Native Americans as well as relationships between one Native American and a Westerner. “A Wigwam Courtship; Intermezzo” by Sadie Koninsky (1903) and “Lackawanna: An Indian Love Song Story from Florida” by Eugene Francis Mickell (1912) show two Native Americans lusting after each other.

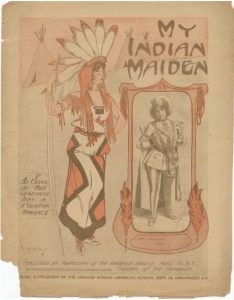

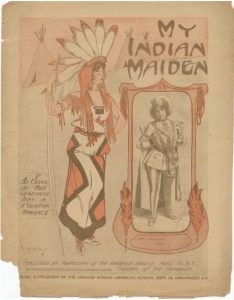

“My Indian Maiden” by Edward Coleman (1904) https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/inharmony/detail.do?action=detail&fullItemID=/lilly/devincent/LL-SDV-083015

Meanwhile, the cover to Edward Coleman’s “My Indian Maiden” (1904) depicts a Native American woman dressed in full regalia with a pleasant expression on her face, while a European man in colonial period clothing stands in the mirror behind her.

It is inconclusive whether depicting these Native American relationships on score covers is for representative purposes or as a form of exoticism. According to Oxford Bibliographies, “exoticism is considered a form of representation in which peoples, places, and cultural practices are depicted as foreign from the perspective of the composer and/or intended audience. In earlier usage of the term, “exoticism” and “exotic” referred to an inherent quality or status of the non-Western other”. It is clear that the illustrators for the score covers thought of Native Americans as the “other” and sought to depict them as stereotypically as possible. Every album cover that I researched with Native American subjects had them depicted in full regalia, surrounded by nature, and often using weapons.

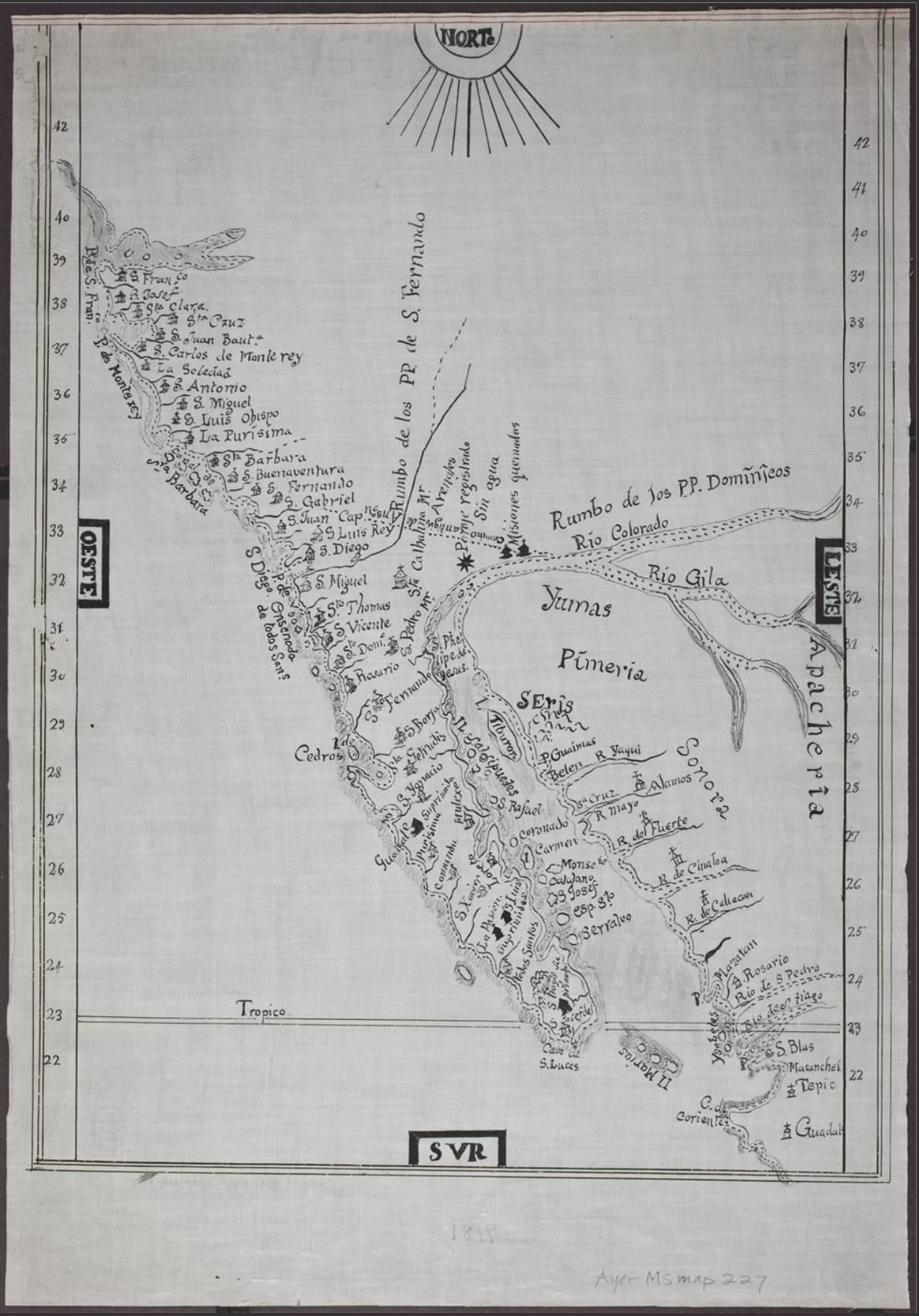

These score covers provide an interesting historical insight into how Westerners viewed Native Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries. Not only were Native Americans thought of as underdeveloped and uncivilized warriors, but Native American relationships served as an exotic spectacle to Westerners. Native Americans were treated by score illustrators as commodities to help increase score profits, instead of actual people. The cover art to “My Indian Maiden” shows that Native American women may have been fetishized by white men especially, which is a dangerous rhetoric to spread. “The Justice Department reports that one in three Native women is raped over her lifetime, while other sources report that many Native women are too demoralized to report rape. Perhaps this is because federal prosecutors decline to prosecute 67 percent of sexual abuse cases, according to the Government Accountability Office. More than 80 percent of sex crimes on reservations are committed by non-Indian men, who are immune from prosecution by tribal courts” (Erdrich, 2013). In fact, a 1915 letter by the U.S. Board of Indian Commissioners addressed to Edward E. Ayer states that attempted rape of Native Americans is “impossible” to prosecute: “Outside of certain specific offenses provided for by the Statute, it is impossible to punish anyone who may have attempted rape, an assault, seduction under the promise of marriage, and theft,” (American Indian Histories and Cultures). There were no punishments for the maltreatment and fetishization of Native Americans during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The anti-Native American attitudes that can still be seen today are evident in the 18th- and 19th-century score covers for pieces inspired by Native American music. Cover art of scores and albums can serve as an extremely credible lens into what life looked like in the past, which can help scholars today determine when and where certain racist attitudes may have begun and how they were perpetuated.

Sources:

“A Wigwam Courtship; Intermezzo / Historic American Sheet Music / Duke Digital Repository.” Duke Digital Collections, https://repository.duke.edu/dc/hasm/b0229.

Erdrich. L. (2013). Also the author of “The Round House.” New York Times Op Ed, February 27, 2013, on page A25: Rape on the Reservation.

“Exoticism.” Obo, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199757824/obo-9780199757824-0123.xml.

“In Harmony: Sheet Music from Indiana.” IN Harmony: Sheet Music from Indiana – Item Details, https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/inharmony/detail.do?action=detail&fullItemID=%2Flilly%2Fdevincent%2FLL-SDV-083015.

Kennedy, Philip. “Alex Steinweiss and the World’s First Record Cover.” Illustration Chronicles, 20 July 2021, https://illustrationchronicles.com/Alex-Steinweiss-and-the-World-s-First-Record-Cover.

“Lackawanna : an Indian Love Song, Story from Florida.” CONTENTDM, Ball State University Digital Media Repository, https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ShtMus/id/13.

“To Mrs. Graham Atkinson. Sioux March & Waltz by Louis Wallis.” Playmakers Repertory Company Playbills, https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/sheetmusic/id/23812.

“U.S. Board of Indian Commissioners Files [Manuscript]: 1912-1922 [ Box 3, Folders 15 to 18].” AMD, American Indian Histories and Cultures, https://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/SearchDetails/Ayer_MS_911_BX03_1#Snippits.