African American spirituals were infused with the experiences and emotions of enslaved people in the south as they utilized these religious folk tunes for praise, worship, and community. Many of these spirituals thrive today, performed by artists such as Nat Cole King, Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, and many more. However, some argue about the origination of these tunes, such as the musicologists recently discussed in class, like Henry Krehbiel and George Pullman Jackson. Throughout this blog post, I will discuss how the privilege of white men allowed scholars like Jackson and Krehbiel to argue the true origin of spirituals and how the power to change the narrative has primarily laid with the European white settlers.

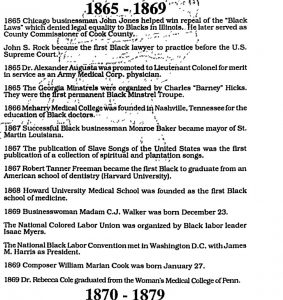

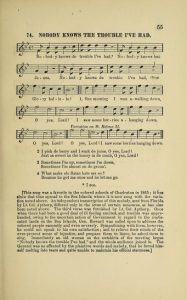

The Primary document below is a piece of a newspaper listing published by the Afro-American Gazette, and it lists in chronological order the history of black achievement. Listed halfway down is the 1867 published book entitled Slave Songs of the United States. This book is also seen below. Written and edited by northern abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware, Slave Songs of the United States was published in 1867. It was prominent in introducing written notation of spirituals that were never shared before; this book was the first space where the famous folk tune Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen was published. The three authors that gathered all 136 spirituals listed spent time during the civil war with recently freed enslaved people and, in turn, learned of the songs they used for worship.

Furthermore, William Allen gives background through the writing of the introduction to the purpose of this book and the biases it might hold. Allen admits that “the difficulty experienced in obtaining absolute correctness is greater than might be supposed by those who have never tried the experiment, and we are far from claiming that we have made no mistakes” (Slave Songs, Pg. iv). His identity as a white scholar with a Harvard degree and title as an educator in the civil war gives him an abundance of authority to hold the narrative of African American Slave songs. Thankfully, the book’s authors provide some credit for the actual creators of the spirituals; however, the main argument is that the privilege the three authors hold allows them to change the narrative just as scholars like Krehbiel and Jackson have done.

Furthermore, William Allen gives background through the writing of the introduction to the purpose of this book and the biases it might hold. Allen admits that “the difficulty experienced in obtaining absolute correctness is greater than might be supposed by those who have never tried the experiment, and we are far from claiming that we have made no mistakes” (Slave Songs, Pg. iv). His identity as a white scholar with a Harvard degree and title as an educator in the civil war gives him an abundance of authority to hold the narrative of African American Slave songs. Thankfully, the book’s authors provide some credit for the actual creators of the spirituals; however, the main argument is that the privilege the three authors hold allows them to change the narrative just as scholars like Krehbiel and Jackson have done.

The score of Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, recorded by Charles Pickard, is a very prominent spiritual performed by many artists in pop culture. Consequently, the piece was recorded during a moment of grief, surrounded by when the population of Charleston. This song was specifically introduced to bring together the community in that moment of frustration. Those in the presence of the performance shared the intensity of emotions that flowed through the crowd. While the authors of this book were too in attendance, there stands to mention that the musicologists never could genuinely capture the integrity of the pieces through western, traditional transcription of music they later wrote down. Allen even remarks on this by stating that the mistakes embedded are “variations.” The issue, however, arises when these variations become the known versions of the original due to white privilege creating authority and power over all narratives.

The score of Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, recorded by Charles Pickard, is a very prominent spiritual performed by many artists in pop culture. Consequently, the piece was recorded during a moment of grief, surrounded by when the population of Charleston. This song was specifically introduced to bring together the community in that moment of frustration. Those in the presence of the performance shared the intensity of emotions that flowed through the crowd. While the authors of this book were too in attendance, there stands to mention that the musicologists never could genuinely capture the integrity of the pieces through western, traditional transcription of music they later wrote down. Allen even remarks on this by stating that the mistakes embedded are “variations.” The issue, however, arises when these variations become the known versions of the original due to white privilege creating authority and power over all narratives.

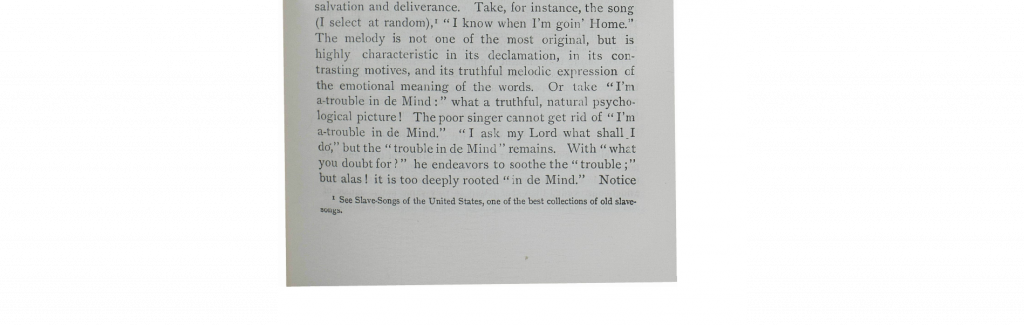

One last primary document I came across is Frederick Louis Ritters’s book, Music in America, where he cites the Slave Songs of the United States and says it is “one of the best collections of old slave songs” (Ritter). At the time, it was the best collection of African American spirituals. Allen did indeed make recognition that these pieces were all derived from African Americans, that the notation depicted is the best that they can do and will only “convey but a faint shadow of the original” (Slave Songs, Pg. iv). Although, if we allow this narrative to represent African American culture and music, we allow authors like Henry Krehbiel and George Pullman Jackson to make claims of the white influence on black tradition.

One last primary document I came across is Frederick Louis Ritters’s book, Music in America, where he cites the Slave Songs of the United States and says it is “one of the best collections of old slave songs” (Ritter). At the time, it was the best collection of African American spirituals. Allen did indeed make recognition that these pieces were all derived from African Americans, that the notation depicted is the best that they can do and will only “convey but a faint shadow of the original” (Slave Songs, Pg. iv). Although, if we allow this narrative to represent African American culture and music, we allow authors like Henry Krehbiel and George Pullman Jackson to make claims of the white influence on black tradition.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVKKRzemX_w

Bibliography

Afro-American Gazette, vol. III, no. 2, 18 Jan. 1993, p. 12. Readex: African American Newspapers, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12A7AD36E8864712%40EANAAA-12C5F06DC6F7F750%402449006-12C5F06DF9520AB0%4017. Accessed 24 Nov. 2022.

Allen, W. F. W. (1867). Slave songs of the United States. Smithsonian Library. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/slavesongsofunit00alle

Wenturiano. (2007, August 24). Louis Armstrong – nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen (1962). YouTube. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from Louis Armstrong – Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen (1962)

Ritter, Frédéric Louis. Music in America by Dr. Frédéric Louis Ritter. New York C. Scribner’s Sons, 1890. Readex: Readex AllSearch, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=ARDX&docref=image/v2%3A%40EAIX-147E02D592F8DF60%40-1514D940AFDB4FF0%40449. Accessed 24 Nov. 2022.