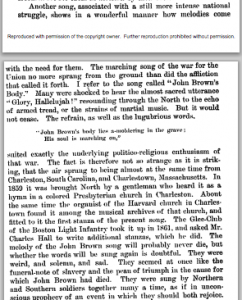

Imagine reading the Sunday morning paper. Hot off the presses, and just delivered to your door in an affluent neighborhood in Huntsville, Alabama – the year is 1882. You skip over the daily news and weather reports to get to your favorite section – the editorials. You skim over the gossip and advertisements, but suddenly, a title catches your eye: “African Wit and Humor. Congressman Cox on the Fun in a Negro’s Character”.

Newspaper entitled “AFRICAN WIT AND HUMOR. Congressman Cox on the fun in a Negro’s Character. (Huntsville Gazette, 1882).

This newspaper article was published in the Huntsville Gazette on March 11th, 1882. The title is eye-catching because it makes a profound claim on the characteristics of black people during the height of the slave trade and the American Civil War in the late 19th century. Reading further into the article, it became apparent that the man giving commentary on the personalities of black people was a white congressman named Samuel S. Cox. Cox was a representative for both the states of Ohio and New York during his tenure in the U.S. House of Representatives. Cox traveled between jobs in the law and political spheres until he ultimately was elected to Congress from 1857-1865, and 1869-1889 (retiring 7 years after this article was published).

Drawing of Samuel Sullivan Cox, date unknown.

The gist of the magazine article is that it recounts the night when Congressman Cox presented a lecture at the Lincoln Center in New York City on the personality trait of humor in African people. It goes on to give multiple examples, which were received with [Laughter] at the ends of each joke:

“The African is like the kaleidoscope changing. He has his extremes of joy and sorrow, sin and pertinence. The elements of his character have puzzled the best analytical tests. The varying and brightly scintillating–flashes of his lighter nature are well-balanced to do this. “Bill,” said my father one day to a negro, “here’s a dram of whiskey for you twenty-five years old.” Looking dubiously at the liquor in the glass Bill said, “Yes masseh, I see; but I declare dat’s de smallest chile fur’s age I’ve ever seed.” [Laughter]”

African Wit and Humor. Congressman Cox on the Fun in a Negro’s Character

This article prompts me to consider our discussions on minstrelsy and black entertainment. Who was Cox’s audience, and what did they take away from his remarks? In an era when minstrelsy thrived, such performances often perpetuated racial caricatures. Cox’s commentary, while seemingly benign, fits within this larger narrative, reinforcing existing stereotypes while providing a space for laughter that masks deeper societal issues. His approach allows the audience to laugh at perceived quirks of black life, subtly reinforcing their social dominance by portraying black individuals as mere figures of humor rather than as complex human beings. This raises important questions about the implications of humor in understanding culture.

The laughter that once echoed in the Lincoln Center is a reminder of how humor can be wielded as both a tool for connection and a weapon of marginalization. By examining these narratives critically, we can better understand the intricate relationship between race, humor, and representation—one that still resonates in contemporary discussions about race and culture in America.

WORKS CITED

- “African Wit and Humor. Congressman Cox on the Fun in a Negro’s Character.” NewsBank, www.infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=4&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=music%2C%20african%20american&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A12B28392F31992D0%40EANAAA-12C175246F8D10B0%402408516-12C175248A6ACB38%401-12C17524EC0B6BD0%40.

- “Cox, Congressman.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/C000839

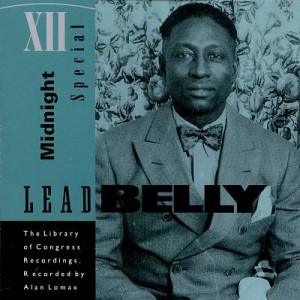

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Figure 2

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3