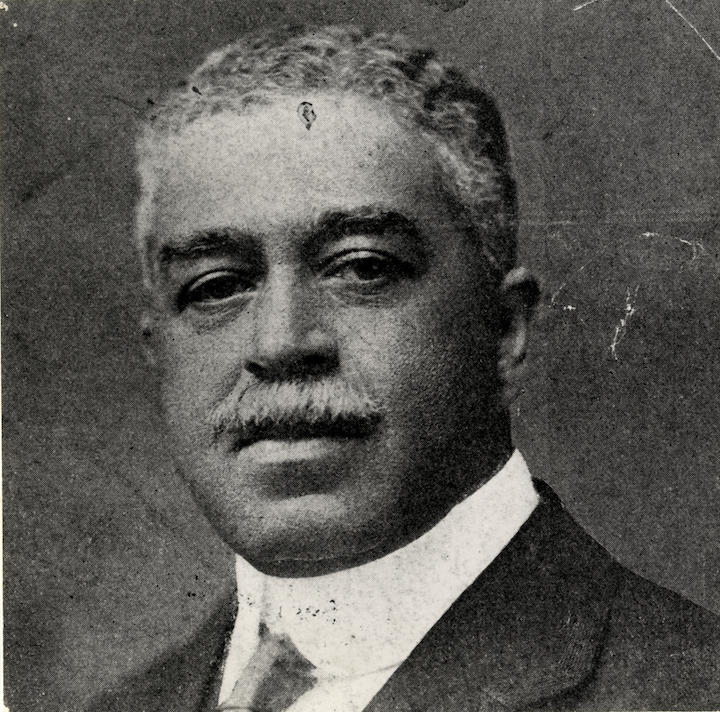

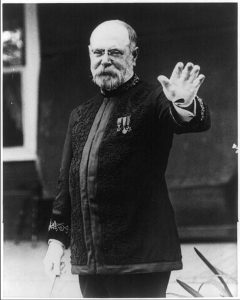

The Cleveland Gazette, a Black-owned newspaper founded in 1883,1 affirms Black composer Samuel Coleridge Taylor as being, “the real thing.”2 During his career, Coleridge-Taylor, like other composers of the time, found meaning and significance in African-American folk tunes.3 Coleridge-Taylor’s works were well-received during his lifetime, the most well-known being The Song of Hiawatha.4 Among many other works, he published a book of piano transcriptions of African-American folk tunes in 1905.5

His success as a composer in Europe led him to America, where he performed various recitals featuring his works.6 Among the works he performed at one recital were four of the piano transcriptions found in his published collection, entitled, “I’m Troubled in Mind,” “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child,” and, “Many Thousands Gone.”7

Twenty-four negro melodies transcribed for the piano by S. Coleridge-Taylor. Op. 59, table of contents8

Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child, transcribed by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor9

When following the trajectory of his career, one cannot help but to draw parallels between Coleridge-Taylor and Antonin Dvorak. Like Dvorak, Coleridge-Taylor was a European composer who spent time in America and took an interest in preserving and using Black folk music as a source of musical inspiration.10 Coleridge-Taylor performed many successful recitals that received complementary reviews, naming him one of the very greatest.11 However, Dvorak’s influence was much greater and his legacy more well-known. These two composers are both equally as American as each other, but only Dvorak is credited with being the great American composer. The relationship between these two composers upholds a legacy of cultural supremacy that devalues Black artists and art until they are discovered, used, and legitimized by a White artist.

1 “Cleveland Gazette: Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Case Western Reserve University.” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University, October 13, 2020. https://case.edu/ech/articles/c/cleveland-gazette.

2 “The ‘Real Thing’ In England’s Musical Circles is S. Coleridge-Taylor, a Colored Man Second Composition.” Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio), December 2, 1899: 1. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B716FE88B82998%40EANAAA-12BAC591E7A454A8%402414991-12BA053406EECF90%400-12D5BD14223677F8%40The%2B%2522Real%2BThing%2522%2BIn%2BEngland%2527s%2BMusical%2BCircles%2Bis%2BS.%2BColeridge-Taylor%252C%2Ba%2BColored%2BMan%2BSecond%2BComposition.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel, and Booker T Washington. Twenty-four negro melodies, transcribed for the piano. Boston: Oliver Ditson Company, 1905. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=F6AI57RNMTY5NTkzMDA4MC44MDIwNDoxOjE0OjE5OS45MS4xODAuMjMx&p_action=doc&p_queryname=18&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-154E9B2175979AC0@S454-15E6DA6A14A2DE10@2

6 “The Great Taylor Recital.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana) XVII, no. 48, December 17, 1904: [5]. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANAAA-12C55E0C65BC8D90%402416832-12C55E0CB03AB1E8%404-12C55E0D903F1E60%40The%2BGreat%2BTaylor%2BRecital.

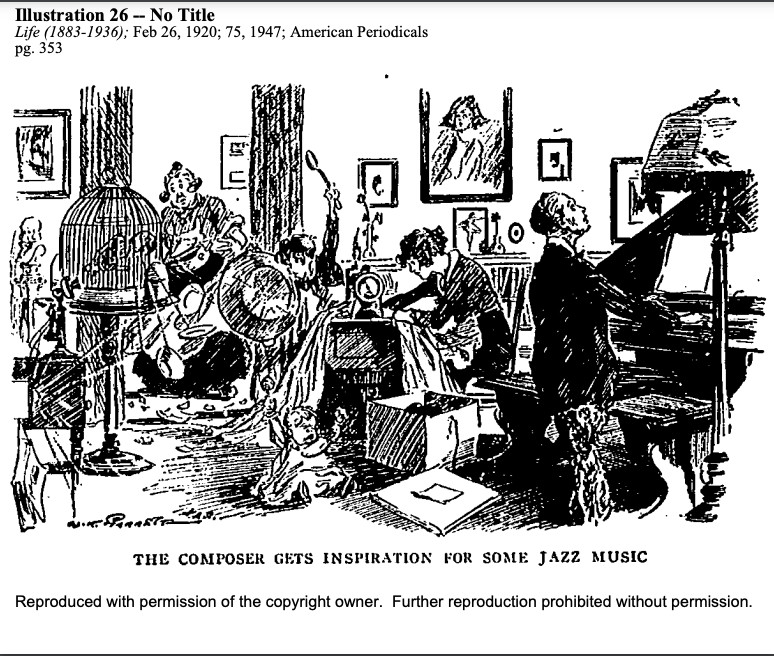

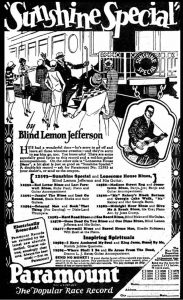

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

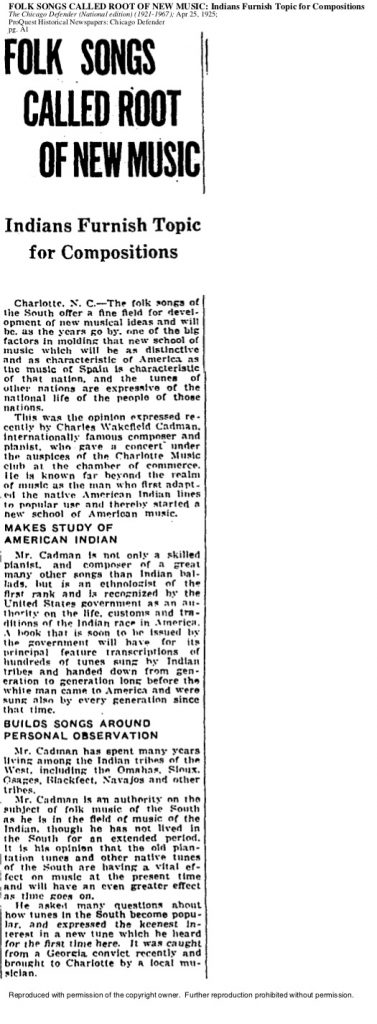

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in