The Fisk Jubilee singers are hailed as key pioneers of “concert spirituals”, arrangements of African-American spirituals meant for the stage. They were extremely successful in their earliest years, around the 1870s: they were invited to perform at the White House, Queen Victoria commissioned a floor-to-ceiling portrait of the original members as a gift, and they raised enough funds on tours in the US and Europe to build the first permanent building at Fisk University.

To investigate the public’s opinion of the Jubilee Singers, I looked to an article in The Aldine, a monthly arts magazine printed in New York during the 1800s. At first glance, the review (from March of 1873) is complimentary. However, upon closer reading, some misconceptions about the Fisk Jubilee Singers become apparent. This article is evidence of how, while the Fisk Jubilee Singers were extremely successful and popular, the public’s perspective during the 1870’s still upheld racist ideas that are often applied to musics outside of the European canon.

The first thing I would like to highlight to this point was that the author claimed the Singers’ skill was natural talent.

“They have art; but it is the product of a rich natural gift, polished by natural taste and discrimination […] A musical voice seems to be a characteristic endowment of their race,”

This idea that musical talent is passed down rather than taught can be historically seen associated with many non-European musical traditions, including African percussion and Appalachian banjo music (as we discussed in class). This tactic “others” the music, and fails to recognize the hard work of the musicians. In this case, although the author is complementing the Jubilee Singers, they also say that the group lacks “cultivation” and “scientific instruction,” a Eurocentric value judgement which reveals the problematic side of this claim.

A second comment of note in this article can be found when the author is discussing the songs that the Fisk Jubilee Singers perform.

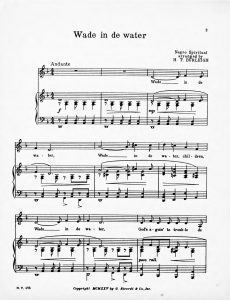

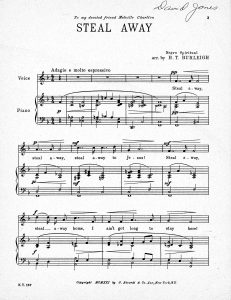

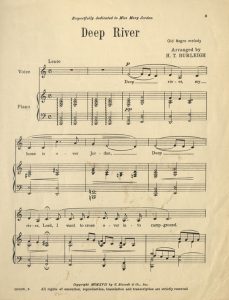

“They are clearly not the product of civilization, and yet an instinct seems to have taught their makers to follow strict musical laws. Wild and irregular as many of them seem on first hearing […] the strangest phrases can be correctly expressed in musical notation.”

When the author refers to “musical laws” and upholds musical notation as the “scientific” way to do things, they imply that this is the right and true way to express music. This reminds me of how transcriptions of Native American music were thought to be sufficient by their creators, but when the transcriptions are compared to audio recordings, there are large discrepancies. In both cases, the European musical framework is assigned more value. In fact, the author says that the way spirituals follow “musical laws” despite their creators lack of formal musical education is proof that these laws are “what the ear requires,” a claim which is ill-conceived in multiple ways.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are an inspiring success story, and they still perform today as one of the most acclaimed choirs in the country, often serving an ambassador role internationally. However, this review makes it clear that even in their success, the Jubilee Singers were not exempt from discrimination and bias in the public eye.

“MUSIC.: THE JUBILEE SINGERS.” The Aldine, A Typographic Art Journal (1871-1873), 03, 1873, 67, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/music/docview/124830318/se-2.

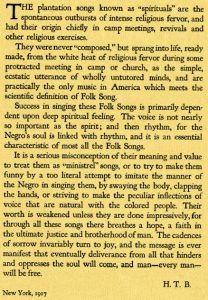

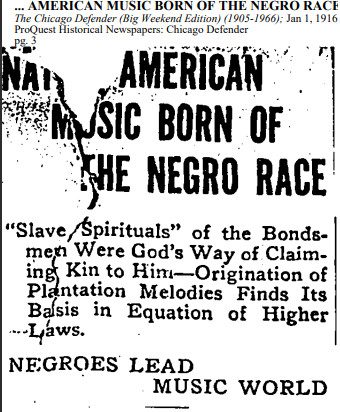

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.