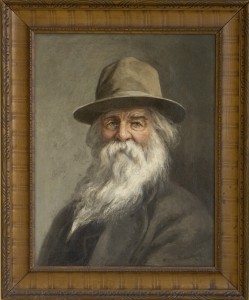

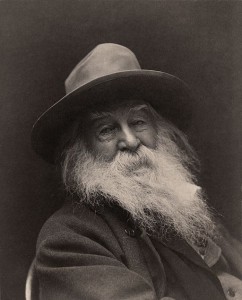

Xanthus Russell Smith painted the posthumous portrait of American writer Walt Whitman in 1897, several years after Whitman’s death.1 The oil study on canvas appears to be based off of a portrait photo which was taken by photographer George C. Cox in 1887. Whitman had loved this photo so much that he titled it “The Laughing Philosopher” and sold the other portraits from the session to supplement his income.2

Whitman lived from 1819 to 1892, spending the majority of his life on the east coast, dying in Camden, New Jersey, He was an American poet, essayist and journalist and as a humanist, his works are regarded as being transitory between transcendentalism and realism with elements of each idea present. He was concerned with politics and abolitionism (although this is not necessarily based on his belief in racial equality) and was wishy washy with his endorsement of abolitionism. There has also been debate over what Whitman’s sexuality was, although this began much later after his death and there is still disagreement among biographers as to whether or not Whitman had even had sexual experiences with men (although having or lacking experience should not be the validating factor as to whether a person truly identifies a certain way).

It is unknown as to whether or not Xanthus Russell Smith was acquainted with Whitman or was instead an admirer of his work. Smith was known for using small brushstrokes and sharp detail. The portrait can be interpreted by many different lenses, including artistic, historical and modern perspectives.

The portrait is composed fairly symmetrically, with Whitman’s shoulders facing at an angle away from the painter and his face squared to the front. The colors of the portrait are muted and neutral, lacking color except for around the eyes, which could be interpreted as a nod towards Whitman’s interpretation of the world, beliefs and persuasions (i.e. gray).

The focal point of the portrait is definitely the eyes. The viewer is drawn to them immediately, then down Whitman’s nose to his shock-white mustache and beard. The eyes are the most lifelike piece of the portrait and along with the rest of the face are almost completely centered in the portrait. However, this positioning is not so much a surprise as it is a given that the focal point of a portrait should be the subject’s face.

The painting is divided down the center of the frame, with one side of the background lighter than the other, and on Whitman’s face, the light patterns seem to be reversed, suggesting that there were two different light sources used in the photograph Smith used or in his interpretation of it. The use of light might be a nod to Whitman’s ideas and philosophy, which went between transcendentalism and realism or to the two sides of his sexuality and the way the public perceived him. The latter interpretation would however be carried into that of the modernist lens as few writers speculated on his sexuality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, Whitman’s poetry has been set to music by many composers, including the music of John Adams, Leonard Bernstein, Benjamin Britten, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Kurt Weill, Roger Sessions and Ned Rorem.

You can view Xanthus Russell Smith’s portrait of Walt Whitman in the Flaten Art Museum reserve collection housed in St. Olaf College’s Dittman Center.

Bibliography

1. Smith, Xanthus Russell. Walt Whitman. 1897. Oil on canvas. 17.5 in x 13.5 in. Dittman Center : Second (2) Floor : Storage Vault : 19A : Flaten Art Museum.

2. Whitman, Walt. Lafayette in Brooklyn. New York: George D. Smith, 1905.

3. Cox, George C. Walt Whitman. 1887. Photograph.