Harvey B. Gaul was an organist and composer in the early 20th century. He worked in various church music positions across the country, but was based in Pittsburgh for 35 years of his career, and was a central fixture of the music community in the city. He is even memorialized by the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble’s composition contest, which bears his name.1

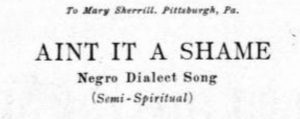

During his prolific career as a composer and church musician, Gaul arranged a few spirituals/folk songs of African-American origin. There are two such examples that I found. The first is a song titled “Ain’t It a Shame,” which is published alongside another song under the larger title “Negro [sic] Dialect Songs.” The other is called “South Carolina Croon Song.” This latter work cites a lyricist named Will Deems, but I was unable to find any information about him. Although definitely not a unique case in his time, Gaul’s arrangements demonstrate perfectly the idea that using notation to transcribe non-Western classical music can be a violent act.

What struck me about the first tune was the title of the larger work, which attributes these songs to Black Americans. Yet the credited arranger being Gaul, and the origin being as vague as an entire race, Gaul is the only one who benefits materially from the publication of this tune. Any sense of giving credit through this title is overshadowed by every other aspect of arrangement. The use of the word “dialect” also seems to other this song by distinguishing the way that Black Americans speak and sing from the way that White Americans do. The subtitle for the tune also labels it as a “semi-spiritual.”2 This appeared odd to me, as it has religious themes, and there’s nothing I have noticed about the tune that would disqualify it as a spiritual. There is an overall sense from these elements of the sheet music that the tunes are not taken entirely seriously as worthwhile music.

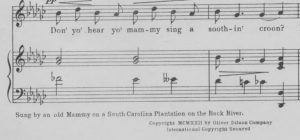

The “South Carolina Croon Song,” despite the title not referring to dialect in the way the other tune does, features lyrics that are notated to indicate the vernacular speech of Black Americans in the south. “Don’ yo’ hear yo’ pappy play de banjo chune?”3 is just one example of this. The sheet music also features a note at the bottom of the first page that says, “Sung by an old Mammy on a South Carolina Plantation on the Back River.”4 This is just plain lazy citation. This woman is not named, and the descriptor “old Mammy” could very easily be interpreted as a diminutive. The written elements of this arrangement already demonstrate a lack of respect for the origins of the music that is being exploited by Gaul.

Finally, what was most striking evidence of the violence of Gaul’s notation of these tunes was the recording I found of White American contralto Kathryn Meisle performing “South Carolina Croon Song.” In the citation, it even indicates that perhaps Will Deems was a pseudonym for Gaul, and not a real lyricist. The recording creates this romanticized vision of the “old Mammy” singing this tune on the “Back River.” The mournful orchestral accompaniment, and the distinctly operatic style of singing are all evidence of a desperate attempt to take a folk tune and cram it into the Western classical tradition. Gaul’s transcriptions are gross misappropriations of these tunes, beyond any justification of preservation or appreciation.

1 Library of Congress. “Harvey Bartlett Gaul (1881-1945).” Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200185354/.

2 “Aint It a Shame : Negro Dialect Song.” Chicago, Ill. : Clayton F. Summy, 1927. Blockson Sheet Music. Temple University Libraries. https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll1/id/5202.

3 “South Carolina Croon Song.” Boston: Oliver Ditson Company, 1922. Vocal Popular Sheet Music Collection. University of Maine. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5657&context=mmb-vp.

4 Ibid.

5 Library of Congress. “South Carolina Croon Song,” October 7, 1924. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-71482/.

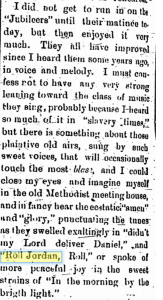

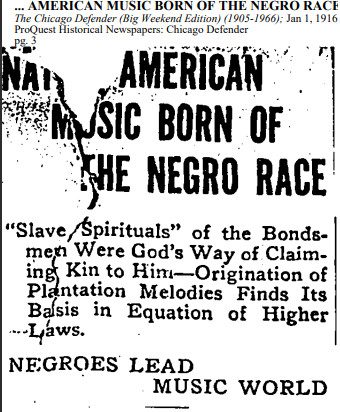

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.

this question for an entire semester. According to The Chicago Defender, it is the song of the enslaved people that truly inspired (or birthed, in their own words) American music. The beginning of this article describes the argument that white people are the source of American music rather than that of bipoc and enslaved people. The Chicago Defender wastes no time in correcting this absurd sentiment. The author goes on to write about bipoc composers, writers and musicians. The author similarly takes a world view that all races are musical, and the truth of their being is expressed through their music. This I agree with, music expresses more than any other medium does. This expression, according to the author is one of divinity, and is an extension of God’s Way. While I don’t consider myself religious (a source of implicit bias I have) the sentiment of the author makes sense.