The first African American or Afro American owned newspaper, The Freedom’s Journal, created a space for Black people to share information, opportunity, creativity, and expression. Despite its short life and changing motivations later in its existence, The Freedom’s Journal set a precedent for the Black voice through knowledge and poetry.

The Freedom’s Journal, founded and edited by John B. Russwurm, Reverend Samuel E. Cornish, and likely other free Black men who are not credited. With issues published weekly from March 16, 1827 to March 28, 1829, the newspaper was circulated in eleven states in the US as well as internationally in a few countries (PBS). Only publishing issues for a little over two years, The Freedom’s Journal inception inspired other Black owned papers over the decades, with “over 40 black-owned and operated papers…established throughout the United States” by the US Civil War (PBS).

Drawing of John B. Russwurm from “The Afro-American Press and its Editors”.

Initially advocating for the abolition of slavery, the newspaper kept its stance on Black Freedom, however, later evolving to be more geared towards promoting the colonization movement, a type of “response movement” to the increasing number of freed slaves and free Black people. Essentially a movement that wanted to remove free Black people from the US to begin colonies in Africa or in the far West, this change in motivations for the newspaper is likely a contribution to the end of The Freedom’s Journal. Readers likely stopped supporting this newfound messaging, in part because the US was home for these free Black people, as well as because of the both underlying and outwardly racist sentiments that motivated the movement.

To S.L.F — A poem likely written by the anonymous poet, Arion, about the feelings they experience parting ways with an unnamed friend.

Within each newspaper of The Freedom’s Journal contained information about schooling, jobs, Black achievement, foreign news, and social affairs, including weddings, deaths and funerals, and life anecdotes that correspondents sent in. A prominent article in most issues was a “poetry” section that included one or two poems, likely from correspondents who submitted stanzas or completed poems to the journal.

Catching my eye throughout my poetry reads was the name “Arion”, likely an alias fittingly inspired from the poet and musician, Arion, from Greek mythology. Arion seemed to be a regular correspondent to the journal, having thirteen of their poems included in thirteen separate issues between 1827 and 1828. Arion submitted poems centering love, loss, emotion and thoughts on the past and changing times, as well as submitting anecdotes from their life, sharing information such as how to cure a toothache with the newspapers’ readers. Unfortunately, I was unable to track down the real identity of Arion, however, it’s clear that The Freedom’s Journal served as an opportunity for writers to put out and practice their art. The newspaper created space for writers and poets to share and engage with their community during times of discrimination and dehumanization.

Other poems featured in the newspaper included topics of Black struggle becoming and existing under enslavement, some notable poems being “The African Chief” by Bryant in the March 16, 1827 issue and “The Tears of a Slave” by Africus in the March 14, 1828 issue. Both poems surround the capture and enslavement of anonymous black individuals from the continent of Africa, noting the hardship and sadness of being torn from family. Other issues included poems that empowered Black people, for example, “The Black Beauty” from Solomon’s Songs beginning with the lines:

‘Black, I am, oh! daughters fair,’

But my beauty is most rare;

Black indeed, appears my skin,

Beauteous, comely, all within

“The Black Beauty” is introduced with words by the New-Haven Chronicle, likely the entity that submitted the poem, describing that this poem is meant to uplift Black people and to show that, despite the oppression they face by White people, both races are humans and are no different from one another apart from their skin color.

These poems highlight the emotions and topics relevant to the free and literate Black person’s experience in the late 1820’s and provided an expressive outlet for writers and poets alike to share with their readers. Though it’s unlikely that enslaved people in the Southern US were able to access these newspapers, the newspapers created opportunities for free Black people in New York and within the Northern US to share information, build community, spread feelings of pain, happiness, loss, and learning.

Bibliography

“Arion Summary”. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024. Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/summary/Arion-Greek-poet-and-musician. Accessed 13 Oct. 2024.

“Freedom’s Journal”. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/newbios/nwsppr/freedom/freedom.html. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

“Freedom’s Journal Newspaper is Published”. African American Registry, 2024. https://aaregistry.org/story/the-first-black-newspaper-freedoms-journal/. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

Penn. I. Garland. “The Afro-American Press and its Editors”. Willey & Co, Massachusetts 1891. Wellesley College Digital Repository, https://repository.wellesley.edu/object/wellesley30303. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024.

“The African Chief.” Freedom’s Journal, 16 Mar. 1827, p. 4. Readex: African American Newspapers, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Asid/infoweb.newsbank.com&svc_dat=EANAAA&req_dat=102FE1F6CA316FA2&rft_val_format=info%3Aofi/fmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=document_id%3Aimage%252Fv2%253A132FB88A16969E1C%2540EANAAA-132FC89EEDB64928%25402388432-132FC0E94E4D3970%25403-1389CB4A75C2513A%2540. Poetry. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024.

“The Colonization Movement.” Indiana Historical Bureau, 2024. https://www.in.gov/history/for-educators/all-resources-for-educators/resources/underground-railroad/gwen-crenshaw/the-colonization-movement/#:~:text=The%20colonization%20movement%20began%20in,remain%20in%20the%20slave%20states. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

“The Black Beauty.” Freedom’s Journal, 8 June 1827, p. 4. Readex: African American Newspapers, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Asid/infoweb.newsbank.com&svc_dat=EANAAA&req_dat=102FE1F6CA316FA2&rft_val_format=info%3Aofi/fmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=document_id%3Aimage%252Fv2%253A132FB88A16969E1C%2540EANAAA-132FC8A94D2B6A08%25402388516-132FC0E9758971C0%25403-138A3AC27A98F47D%2540. Poetry. Accessed 13 Oct. 2024.

“The Tears of a Slave.” Freedom’s Journal, 14 Mar. 1828, p. 4. Readex: African American Newspapers, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info%3Asid/infoweb.newsbank.com&svc_dat=EANAAA&req_dat=102FE1F6CA316FA2&rft_val_format=info%3Aofi/fmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Actx&rft_dat=document_id%3Aimage%252Fv2%253A132FB88A16969E1C%2540EANAAA-132FC8D665FECE80%25402388796-132FC0EA0714AEE0%25403-138B6FD7C12DA122%2540. Poetry. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024.

“To S.L.F”. Freedom’s Journal, 14 Mar. 1828, p. 4. Readex: African American Newspapers, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&t=pubname%3A132FB88A16969E1C%21Freedom%2527s%2BJournal&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=arion&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A132FB88A16969E1C%40EANAAA-132FC8D665FECE80%402388796-132FC0EA0714AEE0%403-138B6FD7C12DA122%40Poetry&firsthit=yes#copy. Poetry. Accessed 12 Oct. 2024

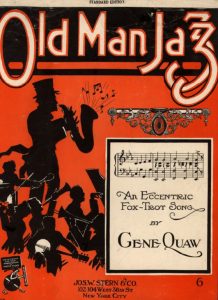

“Old Man Jazz : An Eccentric Fox-Trot Song” written by Gene Quaw hasn’t seen many performances in recent years, and there’s good reason why the first recording that comes up is from 1920. Melodic and rhythmic lines in the opening of the tune veils the main character, Old Man Jazz, in mystery, and the associations and implications of the lyrics throughout the song create a tension between appreciation for Old Man Jazz and the negative aspects to his character.

“Old Man Jazz : An Eccentric Fox-Trot Song” written by Gene Quaw hasn’t seen many performances in recent years, and there’s good reason why the first recording that comes up is from 1920. Melodic and rhythmic lines in the opening of the tune veils the main character, Old Man Jazz, in mystery, and the associations and implications of the lyrics throughout the song create a tension between appreciation for Old Man Jazz and the negative aspects to his character.