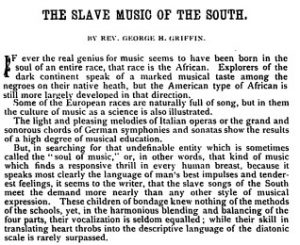

Reverend George H. Griffin was a pastor and accomplished musician who was raised in New York City and graduated from Yale University in 1860.2 He worked at the Plymouth Church in Milford, Massachusetts, and wrote many works on the subject of music in worship throughout his life.2 In this particular work of his, Griffin observes the music of the former southern slaves, and gives his analysis and opinions on the development of said music. This article was published in 1885, twenty years after the end of the American Civil War.

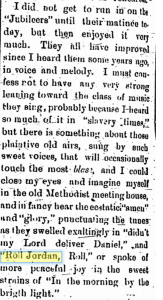

Breaking down his writing, Griffin opens with a description of African music, describing it as “real genius that was born into the soul of an entire race,” as contrasted to European music, which was “more of a science” and “the result of musical education.”1 He also stated that the “emotional largely over-balances the intellectual element, [these] songs, with their fullness of sentiment, seem to realize the ideal.”1 These observations were very typical of white observers of slave music, or spirituals, at the time. Many held the opinion that spirituals were lesser than and derived from the western European classical traditions, and used this opinion to enforce negative stereotypes about African American communities.4 His opinions were also much kinder than others’ at the time, who would describe spirituals as “weird and barbaric madrigals.”3 In this perspective, Griffin’s comparison was much kinder, saying that it was the genius of the soul.

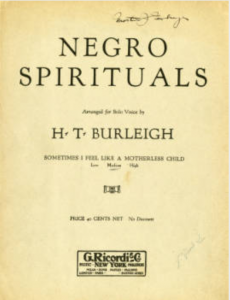

However, Griffin still praised the creation of this music. He referred to the songs as “that kind of music which finds a responsive thrill in every human breast, because it speaks most clearly the language of man’s best impulses and tenderest feelings.”1 This type of infatuation and connection with spirituals was also typical of the time that Griffin wrote this article. A resurgence of these songs by choirs, especially the Fisk Jubilee Singers, sparked this interest, and made white audiences want to further connect them to the overall human experience.

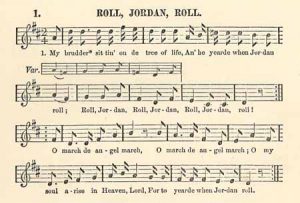

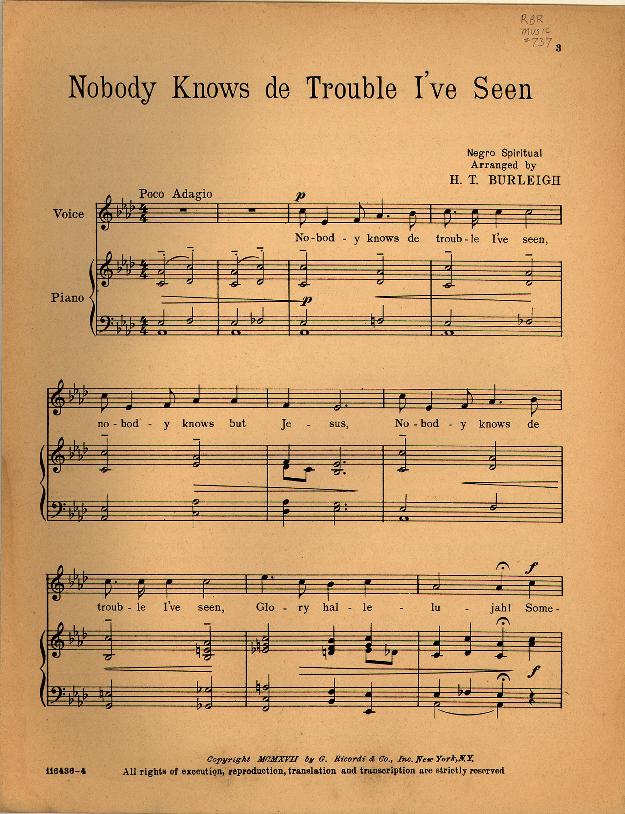

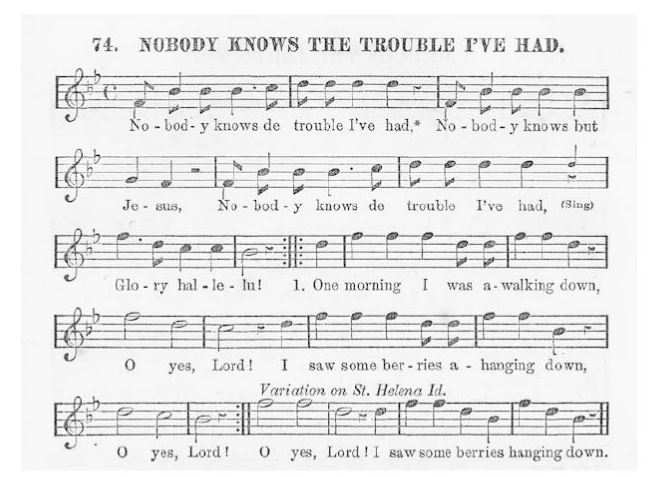

Griffin then goes on to describe the spirituals in terms of Western musical notation, stating that the harmony is rich and the melodies varied and original. He describes the resolutions of chords as abrupt and startling, which he accredits to the rough and rugged experiences they went through. He observes strange points of emphasis and unexpected cadences in rhythm, which he said “makes it unreducible to musical notation.”1 The idea of trying to assign Western notation to these songs is a very interesting idea. Writing any form of music down will cause it to lose a lot of specificities, and especially in things as subtle as tone and emotion which are quite important in spirituals. Griffin’s observations are evident of this, with him stating that so many minute aspects were missing in the writing system he was using.

Lastly, Griffin speaks on the fact that these musical selections came from a place of agonies unknown, but have “the joy of a present salvation, and the hope of a glorious home of freedom beyond the grave.”1 As a pastor, Griffin understood the idea of salvation of life beyond death, and was able to comprehend the reasoning behind these songs. He was able to connect the fact that it rose from a desire of salvation, and a hope for a free soul after death. This was opposed to other white observers of spirituals who would try to convince themselves that the slaves were singing because they were happy to be enslaved,4 which was an incorrect and completely racist assumption.

Overall, Griffin’s article is a great, positive reflection of white perspective of spirituals during the late nineteenth century.

Works Cited:

1 THE SLAVE MUSIC OF THE SOUTH. Griffin, George H. The Musical Visitor, a Magazine of Musical LIterature and Music (1883-1897). Vol. 14, Iss. 2, (Feb 1885): 35. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/137490866/4A4769645E1A4F0DPQ/19?accountid=351&sourcetype=Magazines

2 REV. GEORGE H. GRIFFIN. Congregationalist (1891-1901); Boston Vol. 79, Iss. 37, (Sep 13, 1894): 355.https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/124232810/95A38D77EA848B3PQ/2?accountid=351&sourcetype=Magazines

3 THE MUSIC OF BLACK AMERICANS. Eileen Southern.

4 WHITE AND NEGRO SPIRITUALS. George Pullen Jackson.