Ethel Cain is the pseudonym of Hayden Silas Anhedönia, a singer song-writer with a cult following of mostly young liberal arts students. Her most famous project is her 2022 concept album “Preacher’s Daughter,” which as my friend Kaya said is “not really the right thing to listen to on a roadtrip at night.” The concept album ends with Ethel Cain being cannibalized by a lover. Throughout, it deals with themes of abuse, family secrets, religion, and the American landscape. Sonically, “Preacher’s Daughter” is a combination of ambient music, folk, and rock. The album can be seen as a consideration of the Southern Gothic Genre, with its themes of despair, depravity, and the haunting of the present by the past. It’s genuinely so beautiful— my favorite tracks are “American Teenager,” “Sun Bleached Flies,” and “Strangers.”

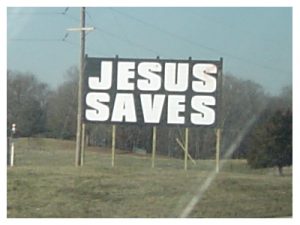

The theological dimension of this work is also fascinating to me. The oft quoted line “God loves you, but not enough to save you,” well, I think that it’s very honest, especially in a case like Ethel Cain’s. She spends a portion of the album on the road with the man who will eventually murder her. She must have seen a hundred billboards with JESUS SAVES plastered on them. But Jesus doesn’t save Ethel from her horrific fate. How can the good God of American Evangelical Christianity, who offers peace, salvation, and is often said by televangelists to offer earthly prosperity etc. allow this horror? Cain’s suffering is often compared explicitly to Christ’s throughout the album.

An analysis that would do theodicy and christology in “Preacher’s Daughter” justice is beyond the scope of this blogpost— however, I would like to examine the song “American Teenager.” It is the most typical pop song on the album— it feels like it could have been written in 80s or 90s, with a catchy chorus, some sparkly synth, and an electric guitar part that sounds quite like Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” (at about 3:43-4:00 in American Teenager, at about 1:00-1:06 in Don’t Stop Believin’). I’ve never been on a highway and not had “Don’t Stop Believin’” come on the radio. Both songs evoke a peculiar feeling— the same feeling I get driving along the endless highways of the U.S. at once home and homesick: complete isolation, the particular derelict buildings outside my window are alien to me; but also a sense of comfortable familiarity, I’m sure I’ve seen them before. This paradox— total alienation as well as total identification is what allows “Preacher’s Daughter” to work.

Cain said in a statement to Pitchfork that the track is deals with her frustration with the American Dream. Particularly interesting is this: “What they don’t tell you is that you need your neighbor more than your country needs you.” Which, of course is the opposite of what her character expresses in this song: “I don’t need anything from anyone/It’s just not my year/But I’m all good out here.” Still, the isolation isn’t complete:

And I feel it there

In the middle of the night

When the lights go out

And I’m all alone again

[Or the second time through]

When the lights go out

But I’m still standing here.

There is both a conspicuous presence of something (I feel it there), but also absence of everything besides this, and Cain herself. The track features a lot of reverb, especially on the vocals, and I cannot help but think this is intentional: Cain is unable to fully break through her isolation. She is her own constant companion, and whatever other presence is there remains somewhat remote to her. In the chorus, she sings: “Say what you want, but say it like you mean it/With your fists for once.” She is seeking sincerity, but there is the troubling implication that the only way it could truly be expressed to her would be through violence. This is perhaps mirrored in the theology of the album: In “American Teenager,” she somewhat ironically prays “Jesus, if you’re listening let me handle my liquor/And Jesus, if You’re there/Why do I feel alone in this room with You?” But in the track “Ptolomea,” when Ethel Cain is murdered, we hear this blessing: “Blessed be the children/Each and every one come to know their god through some senseless act of violence.” I could start writing about the place of violence in Christian theology and what all this means… and I would like to. But I think for the sake of this blog post, I will have to leave my inquiry here (for now), with an anecdote. This fall, I attended a dance at my college and for some reason one of the DJs chose “American Teenager.” It struck me as strange, to pick a song from the concept album about cannibalism to get a room full of college students to dance, but there I was dancing. It was too loud for me, but I took out my earplugs anyway. By the end my cheeks were wet, and my mouth was open in a silent smiling scream with the lyrics. I had encountered something. Preacher’s Daughter is a sublime work—whatever presence Ethel Cain is feeling in the absence around her, I feel too and it is overwhelming.

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)

Photo by Enrico Tamayo, by courtesy of artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and Pace Gallery(2024)