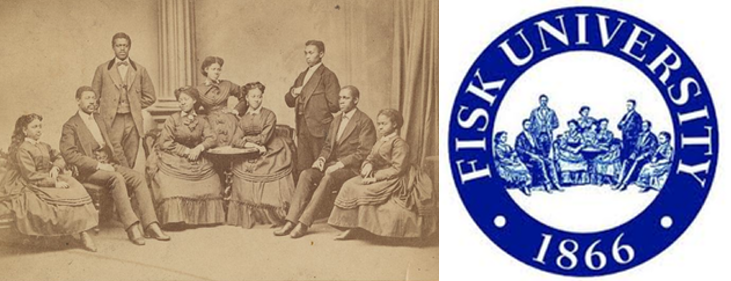

The Fisk Jubilee singers are hailed as key pioneers of “concert spirituals”, arrangements of African-American spirituals meant for the stage. They were extremely successful in their earliest years, around the 1870s: they were invited to perform at the White House, Queen Victoria commissioned a floor-to-ceiling portrait of the original members as a gift, and they raised enough funds on tours in the US and Europe to build the first permanent building at Fisk University.

To investigate the public’s opinion of the Jubilee Singers, I looked to an article in The Aldine, a monthly arts magazine printed in New York during the 1800s. At first glance, the review (from March of 1873) is complimentary. However, upon closer reading, some misconceptions about the Fisk Jubilee Singers become apparent. This article is evidence of how, while the Fisk Jubilee Singers were extremely successful and popular, the public’s perspective during the 1870’s still upheld racist ideas that are often applied to musics outside of the European canon.

The first thing I would like to highlight to this point was that the author claimed the Singers’ skill was natural talent.

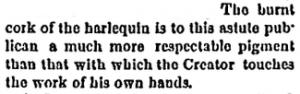

“They have art; but it is the product of a rich natural gift, polished by natural taste and discrimination […] A musical voice seems to be a characteristic endowment of their race,”

This idea that musical talent is passed down rather than taught can be historically seen associated with many non-European musical traditions, including African percussion and Appalachian banjo music (as we discussed in class). This tactic “others” the music, and fails to recognize the hard work of the musicians. In this case, although the author is complementing the Jubilee Singers, they also say that the group lacks “cultivation” and “scientific instruction,” a Eurocentric value judgement which reveals the problematic side of this claim.

A second comment of note in this article can be found when the author is discussing the songs that the Fisk Jubilee Singers perform.

“They are clearly not the product of civilization, and yet an instinct seems to have taught their makers to follow strict musical laws. Wild and irregular as many of them seem on first hearing […] the strangest phrases can be correctly expressed in musical notation.”

When the author refers to “musical laws” and upholds musical notation as the “scientific” way to do things, they imply that this is the right and true way to express music. This reminds me of how transcriptions of Native American music were thought to be sufficient by their creators, but when the transcriptions are compared to audio recordings, there are large discrepancies. In both cases, the European musical framework is assigned more value. In fact, the author says that the way spirituals follow “musical laws” despite their creators lack of formal musical education is proof that these laws are “what the ear requires,” a claim which is ill-conceived in multiple ways.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are an inspiring success story, and they still perform today as one of the most acclaimed choirs in the country, often serving an ambassador role internationally. However, this review makes it clear that even in their success, the Jubilee Singers were not exempt from discrimination and bias in the public eye.

“MUSIC.: THE JUBILEE SINGERS.” The Aldine, A Typographic Art Journal (1871-1873), 03, 1873, 67, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/music/docview/124830318/se-2.

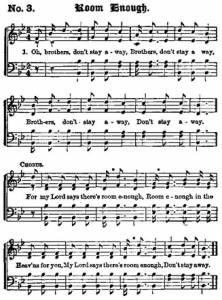

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

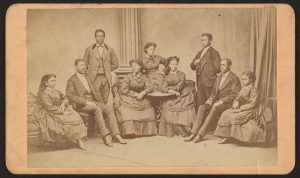

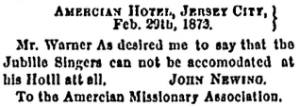

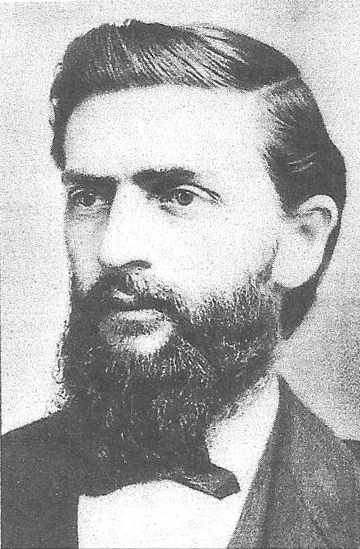

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

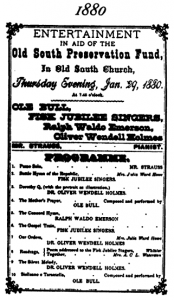

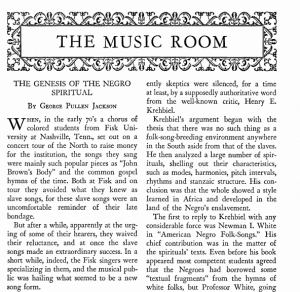

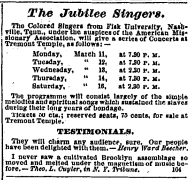

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

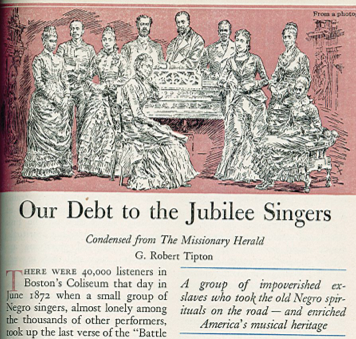

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.