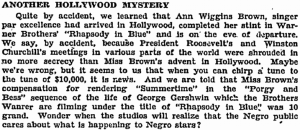

From the late 19th century throughout the early 20th century, minstrel shows were as American as apple pie. In his 1921 book, How to Put on a Minstrel Show, Harold Rossiter provides a standardized and systematic approach to organizing a Minstrel show, which only alludes to its popularity in the American eye. Minstrel shows were such an institution that there was an established process to conducting one, from rehearsals to advertising. Rossiter discusses the canon of minstrel songs, and how to create a set list of songs to include. To further the notion of how dominant minstrel shows were in the sphere of American entertainment, he also recommends that organizers should treat minstrel shows much like a carnival: “I might add that a Minstrel Show that is ‘billed like a circus’ will nearly always be successful” (23)1. The fact that minstrel shows were so widespread that they necessitated common procedures cannot go understated.

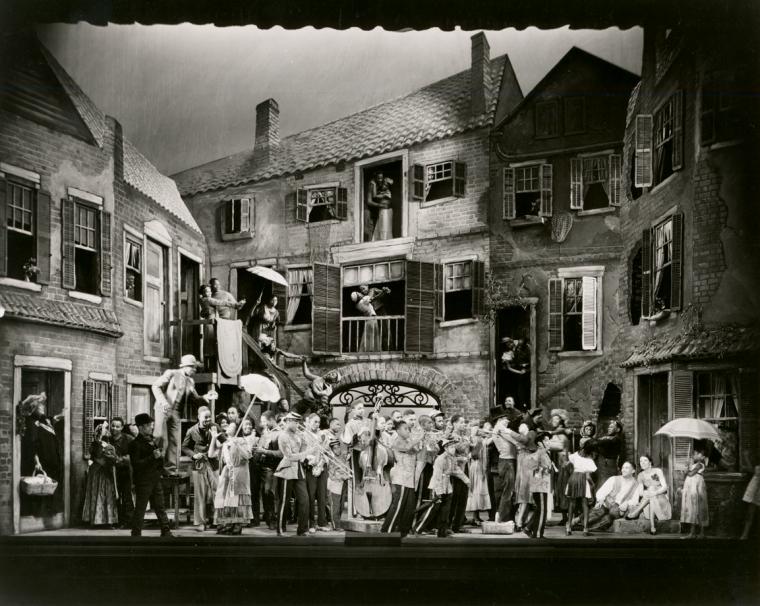

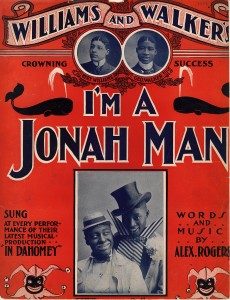

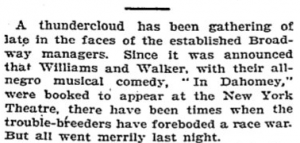

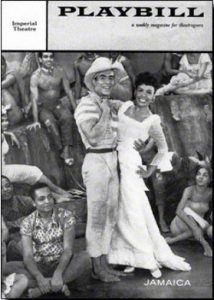

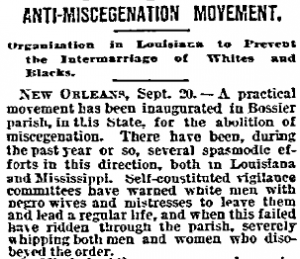

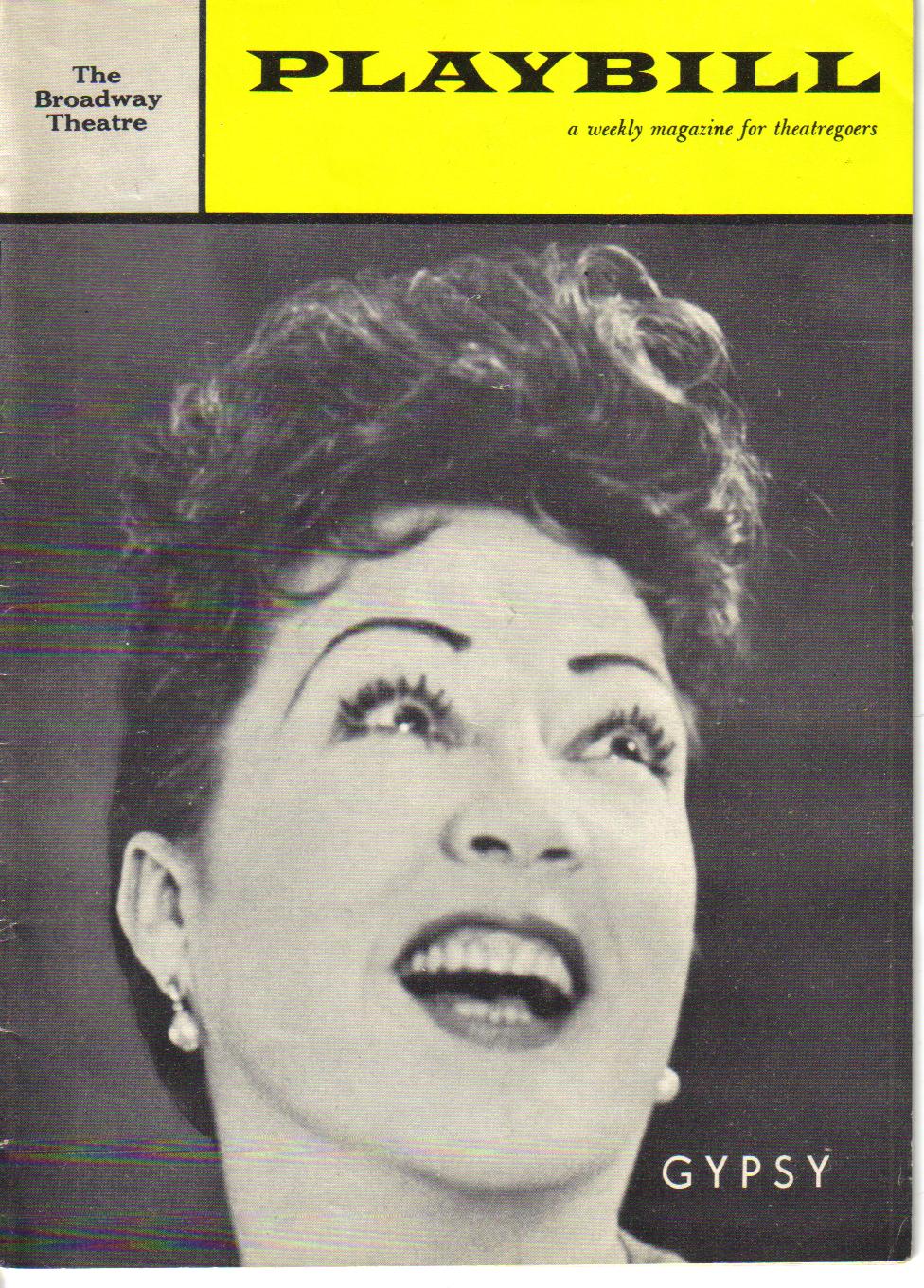

Rachel Sussman argues in “The Carnavalizing of Race” that this popularity stems from minstrel shows giving white people an escape from the pomp and circumstance of 19th century society. At these shows, white people were able to indulge their prejudices and biases with reckless abandon. The minstrel show “…was the predecessor to the broadway musical…”, and was considered American theater in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many even lovingly referred to it as “American National Opera” (80)2. Racism was so central to the American identity that professing black inferiority could go as far as to be considered a thespian art. The American entertainment industry has continued to keep the black caricature in our cultural memory from Looney Tunes to Madea.

1Rossiter, Harold. 1921. How to Put on a Minstrel Show.

2Sussman, Rachel. “The Carnavalizing of Race.” Etnofoor 14, no. 2 (2001): 79–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25758014.

Works Cited

Rossiter, Harold. 1921. How to Put on a Minstrel Show.

Sussman, Rachel. “The Carnavalizing of Race.” Etnofoor 14, no. 2 (2001): 79–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25758014.

Rose, Steve. 2018. “Tyler Perry: The Creator of a Racial Stereotype or the Greatest Indie Film-Maker of All Time?” The Guardian. The Guardian. November 12, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/nov/12/tyler-perry-madea-creator-of-a-racial-stereotype-or-the-greatest-indie-film-maker-ever.

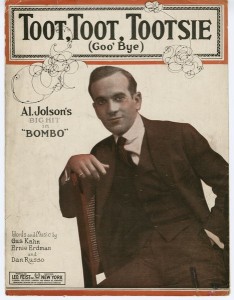

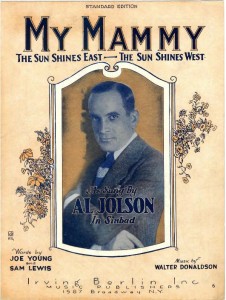

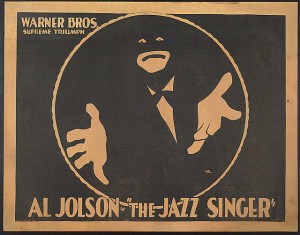

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.

Much of the success of The Jazz Singer in 1927 is due to the massive popularity of the star Al Jolson. Regular concert goers and musical theater fans were familiar with Jolson who performed to sold-out audiences at the Winter Garden theater on Broadway. Jolson began performing in blackface make-up early in his career when he realized that it made him even more popular.