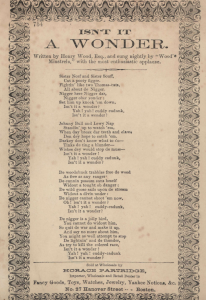

This week I found some painfully real minstrel primary source material and just want to warn readers that I deal with some racist material in this blog post. I came across a minstrel song entitled “Isn’t it a Wonder?” which isn’t at all as innocent as the title sounds. Written in 1861 by Henry Wood, “Isn’t it a Wonder?” would have been performed at a minstrel show by Wood’s group, “Wood’s Minstrels.” It is written in a thick dialect, and is full of stereotypes. Blacks are compared to a variety of animals, and are portrayed as confused and unintelligent.

The message of the song is made explicit in the last stanza. Wood encourages white audiences to adjust to the changing society and to stop trying to “kill the colored race.” It is important to note that this song was written in 1861 – marking the year Lincoln was inaugurated and the start of the Civil War. One possible interpretation of this song is that it highlights the fear and uncertainty that many whites felt about slavery coming to an end. Another interpretation is that it expresses the sick and twisted appreciation whites had for black culture, as it was useful for mockery, entertainment/minstrel shows, and to escape social norms.

Fast-forward 156 years. Jay-Z releases the music video for “The Story of O.J.” which uses many of the inaccurate techniques that minstrelsy did to portray black people. It is drawn in a black and white cartoon style, and presents the viewer with a flood of stereotypical images of black people — they are monkeys, slaves, jazz players, and football players just to name a few. The characters resemble old Disney cartoons, such as Steamboat Willie, which most likely had ties to minstrelsy. We understand this due to the white gloves, over exaggerated animalistic facial features, and caveman portrayal of a child playing the bones. So, why does Jay-Z use these stereotypes? And why now?

I believe Jay-Z’s use of these racist stereotypes found in minstrelsy highlights his message about race in America – we’re dealing with the same issues now. He also addresses the racism within the black community, and the struggle for financial freedom and responsibility. In this music video Jay-Z responds to one of the problems that minstrelsy and songs like “Isn’t it a Wonder?” pose– the comedic relief that blacks provide to white audiences. Jay-Z expresses that no matter what black people do they are still exploited for profit and treated as second class citizens.

Sources

Wood, Henry. Isn’t it a Wonder. 1961. http://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=F59V55CJMTUxMDgwMTg5MC44MDEyOTQ6MToxMzoxMzAuNzEuMjI4Ljgy&p_action=doc&p_docnum=2000&p_queryname=2&p_docref=v2:10D2F64C960591AE@EAIX-10F453B3EBFA3590@925-@1