Celia Cruz, also known as the “Queen of Salsa”, was born on October 21, 1924 in Havana Cuba. She lived with her family father mother and three siblings and as many as fourteen other relatives. She would often sing her younger siblings to sleep. At this time, the career as a singer was unbecoming for a young woman so her parents insisted she get her education. After much persuading by Celia and her mother to her father, she enrolled at the National Conservatory of Music upon her high school graduation. There she studied music theory and voice and she continued to perform on Cuban radio stations such as: Radio Cadena, Radio Progreso, and Radio Unión.

Celia was recruited to be the lead singer of La Sonora Matancera. She joined the group and on their tour to Mexico, the never returned to Cuba in fear of Fidel Castro’s regimen. From Mexico, she moved to Los Angeles where she got a contract with a night club that made her eligible for American citizenship. She met Pedro Knight who became her husband and later her manager.

After a lull in demand for latin music in the 1960s in the United States, Celia relit the flame when she performed with the Tito Puente Orchestra. By the 1970s, SalsaTito Puente Orchestra. became very popular in the US. This kickstarted her career leading her to perform in performances such as:

“… Larry Harlow’s Latin opera Hommy at Carnegie Hall in 1973, performing with leading salsa interpreters such as Johnny Pacheco, Bobby Valentín, Andy Montañez, Willie Colón, Ray Barreto, Papo Lucca, Pete “El Conde” Rodríguez, and eventually recording with the most important group of the time, the Fania All Stars, Cruz was at the center of the salsa revolution and soon became one of the top interpreters of salsa in Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States. Hits such as “Usted Abusó” (You Abused Me), “El Guabà” (Scorpion), and “Yerbero Moderno” (Modern Folk Healer) as uniquely interpreted by Cruz and her accomplished partners, have become salsa classics …” – Serafina Méndez

Celia Cruz is a strong, talent latina woman who has played a pivotal role in the world of salsa music in the United States. She held her title “Queen of Salsa” even though her recent passing on June 13th 2002.

Work Cited

Méndez, Serafina Méndez. “Celia Cruz.” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2017, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1326499. Accessed 12 Nov. 2017.

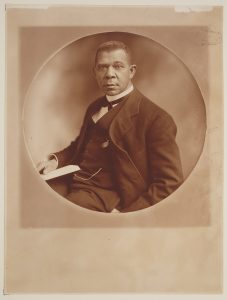

[Celia Cruz, full-length portrait, facing front, on stage]. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,