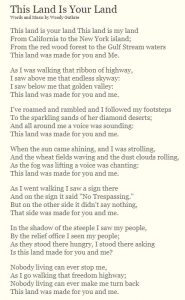

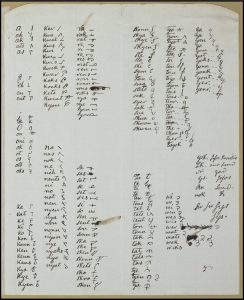

Road to Singapore. 1939. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, http://cdm16786.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/sayre/id/17768. Dorothy Lamour, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope (left to right) in The Road to Singapore. Lamour performs ‘womanly’ tasks while the men relax.

Bing Crosby and Bob Hope made many films together, the most well-known being their Road pictures, of which the duo made seven between 1940 and 1947.1 It isn’t much of a series, as the characters’ names are different in every movie, but their characters and friendship are always the same types–one conniving yet charming businessman (Crosby) and one sucker (Hope). They’re always fighting over the same type of girl, played by Dorothy Lamour, and she always ends up with Crosby’s character. The only differences among these films are the locations. The first picture they made was The Road to Singapore (Schertzinger, 1940), and a still from the film is featured above. These movies are hilarious and remain classics because of the duo’s constant banter, sarcasm, breaking of the fourth wall, self-mockery, and all-around ridiculous shenanigans. However, what Singapore and the others that followed are guilty of is cultural appropriation.

Kenan Malik describes cultural appropriation as “not theft but messy interaction.”2 These films interact with several different cultures in problematic ways. Just watching the trailers illustrates some of the manners with which Hollywood has engaged with and represented other cultures.

All the films exoticize the ‘Other,’ especially the women. The Road pictures depict foreign locations as paradises of simplistic living, where women are either sex objects or homemakers. Singapore features a quite misogynistic view of Lamour’s native-Singaporean character and some quasi-blackface; Zanzibar depicts a typically-stereotyped, cannibalistic, superstitious, unintelligent African tribe; Morocco plays on stereotypes of the Middle East and pokes fun at the mentally disabled; the list goes on, I’m afraid.

I don’t believe these films intended to be super sexist and racist. It was another time, after all. Also, they don’t exactly ask to be taken seriously. I think it’s pretty obvious they aren’t attempting to give an accurate portrayal of other cultures. They are just trying to entertain audiences with some escapism from war time. The focus isn’t really on educating viewers; it’s more about the snappy dialogue between Hope and Crosby. The exotic locations only provided a ridiculous backdrop. Granted, the films added to stereotypes of the day and didn’t necessarily help matters, but they could have been worse.

As long as people know not to take these films seriously, Hope and Crosby are a classic duo and are worth a watch.

1 Murray, Noel. “Hope and Crosby’s Road movies paved the way for future wiseacres.” The A.V. Club. https://film.avclub.com/hope-and-crosby-s-road-movies-paved-the-way-for-future-1798243895.

2 Malik, Kenan. “In Defense of Cultural Appropriation.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/14/opinion/in-defense-of-cultural-appropriation.html?smid=pl-share&_r=0.