The development of the first two centuries of The United States proposed lots of new ideas, new morals, new plans, and of course new art. However, not all of this material, especially art, was considered “new,” but rather stolen, and a big target of this thievery was towards slaves. Slaves often expressed religious yearning, which slowly transformed into gospel, soul, blues, and then even jazz music and beyond. The preservation of this music is astonishing, as we continue to praise these styles of music today, but this preservation must not have been easy, especially with a world of inequality at the time.

“According to the Senior Pastor of Canaan Baptist Church in Harlem, Blacks who lost faith in God following the Civil War began to sing the blues instead of spirituals. The same beat that the Black folks dance to on Saturday night is the same beat they shout to on Sunday morning.”

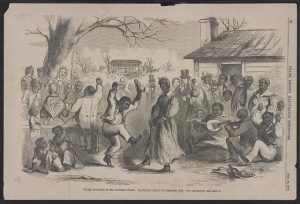

This gathering and celebrating of black spirituals became a time where Black Americans could feel appreciated and grew into bigger gatherings quickly. “They gathered periodically for huge festivals where they danced in the African way to the music of homemade instruments and African songs.” However, white, often slave owners, picked up on the musical talents of black folk and realized that they could profit even further off of their slaves. “In many places black men were given music instruction so that they could serve their masters professionally: by playing classical music in the home for the personal entertainment of the slave-masters’ households.”

“The Dance in Congo Place, New Orleans, accompanied by musical instruments and songs in various African tongues. Drawing by E.W. Kemble in 1885-1886”

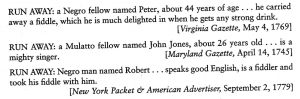

They would be taught popular classical instruments like violins, basses, flutes, and trumpets, to name a few. Sure, many Black Americans might have enjoyed the music of Western European tradition they were forced to perform (that is something I cannot assume, but rather can ponder), but it was not music they could call their own. The preservation of African music in America began with the reluctance of giving up African culture.

Clovis Sanders’ newspaper article from June 7th, 1969 states the following: “Let’s go over some records, such as: “We Got More Soul,””Don’t Let The Jones’ Get You Down,””Why I Sing The Blues,””Nobody To Give Me Nothin,” and “Choice of Colors.” The Impressions are truly trying to get a point across, and this point simply is to be proud. They do this by asking “if you had a choice of colors, which one would you choose my brother?”

The pridefulness many African Americans had during the late 1800s and early 1900s was evident in their art. Their spirituals were heard in different lights, from different instruments to new harmonic ideas, to even new developments of African origin within various American cities.

“If we speak of music, the features such as basic rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic devices were transplanted almost intact rather than isolated songs, dances, or instruments,” says Amiri Baraka, an American writer, in Blues People. African Americans adapted from their tradition and cultural values to the values of Western European culture, to blending the two to tie back into African culture through the implementation of new instruments (trumpets, basses, violins) that were often accessible to them because of slavery.

Samuel Floyd suggested that “black music was expressive of cultural memory, and black-music making was the translation of the memory into sound and the sound into memory. Cultural memory, as a reference to vaguely “known” musical and cultural processes and procedures, is a valid and meaningful way of accounting for the subjective, spiritual, quality of the music and aesthetic behaviors of a culture.” Generations after generations will continue to expand off of their differences in memory from one to another. However, visualizing the roots of African music into the United States helps us unload the deeper meaning the progression of styles of African music has on American culture.