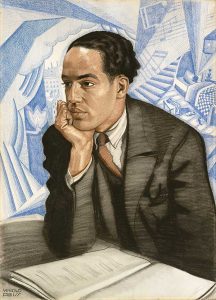

The Chicago Defender was one of the most important newspapers of its time. The first black newspaper to have a circulation of over 100,000 copies1, the Defender was read all throughout Chicago and the South. In addition, almost two thirds of its readers lived outside of Chicago. Within the Defender was a column written by David Peyton called “The Musical Bunch” which wasn’t as much aimed at the consumer as much as it was the musician. Peyton would encourage “…his readers, whom he referred to as “the Musical Bunch,” to practice their instruments, attend engagements, arrive punctually for gigs, perform well, and above all to behave in a professional manner” (Waits 2013) 2.

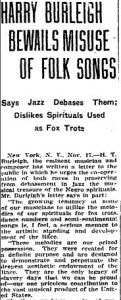

While Peyton was supportive of black musicians, he was derisive towards jazz as a genre. While he was glad that playing jazz was a means for black musicians to be successful, he wrote in 1927 that jazz did little to supplement musicians from an artistic standpoint3. To him, jazz was raucous and illegitimate; full of “incorrect fingerings”. This perspective is echoed in Anne Faulkner’s article, “Does Jazz Put the Sin in Syncopation”, where she describes jazz as a destructive influence on American popular music. Similar to Faulkner, Peyton makes a distinction between orchestrated jazz and the kind found in bars. Both found the latter to be, in Peyton’s words, “barbaric, discordant, wild, shrieky music” that tainted otherwise talented musicians.

While Peyton denied the merit of jazz, what he could not deny was its overwhelming popularity. Even this concession, however, was filled with lament. Further in his July, 1927 edition of “The Musical Bunch”, Peyton discusses how jazz has expanded throughout the American and international sphere, but he applauds the “high calibre” Europeans that would rather import American jazz than learn the tradition themselves. Peyton, who was a pianist and orchestra leader at the time, also mentioned that he would only play jazz briefly upon request due to its popularity.

While it is easy to write of people like Anne Faulkner as fearful racists, it was curious to see that a black musician would so aggressively deride jazz. He wanted for black musicians to be successful in the music business, but only under the Western musical canon, which he believed to be uniquely refined and technical. Jazz, to him, a means to bread on the table, not real music.

1“The Chicago Defender.” n.d. www.pbs.org. Accessed November 8, 2023. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/defender.html#:~:text=The%20Chicago%20Defender%20was%20the.

2Waits, Sarah A., “”Listen to the Wild Discord”: Jazz in the Chicago Defender and the Louisiana Weekly, 1925-1929″ (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1676. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1676

3Peyton, Dave. “THE MUSICAL BUNCH: WHAT JAZZ HAS DONE.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jul 16, 1927. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/musical-bunch/docview/492206986/se-2.

Works Cited

“The Chicago Defender.” n.d. www.pbs.org. Accessed November 8, 2023. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/news_bios/defender.html#:~:text=The%20Chicago%20Defender%20was%20the.

Waits, Sarah A., “”Listen to the Wild Discord”: Jazz in the Chicago Defender and the Louisiana Weekly, 1925-1929″ (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1676. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1676

Walser, Robert. 2015. Keeping Time : Readings in Jazz History. New York: Oxford University Press.