“Built to serve citizens of all races,” the Regal Theater in downtown Chicago was a sight to behold in 1928. Styled with Moorish architecture – which if you didn’t know is a type of Islamic architecture – it was complete with a canopy overhead, a hydraulic curtain, and an electric organ that could rise and fall at the front of the stage.

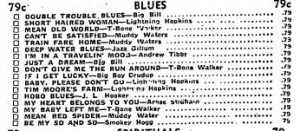

Throughout the years, this theater was used for many performances, covering diverse forms of music, dance, and comedy, including an orchestra well known for playing at a Show Boat cafe in downtown Chicago.

This venue was also important to the time known as the “Chitlin’ Circuit” which housed performances by many well-known artists like Ella Fitzgerald, Nat “King” Cole, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington between 1920 and 1940. The Regal Theater was a major influence on black culture, as it was one of the first entertainment buildings open to black audiences.

With the development of technology like radio and television, the Regal Theater filed for bankruptcy and shut down in 1968, but it wasn’t over yet. The Avalon Theater opened within a year of the Regal Theater in 1927 but operated solely as a movie theater until it closed in 1967. After a few years, it was bought and refurnished in honor of the original Regal Theater, and renamed “The New Regal Theater.” You’ll note below how these renovations look similar to the first image in this post.

Sources:

- https://www.proquest.com/hnpchicagodefender/historical-newspapers/interior-regal-theater/docview/492180972/sem-2?accountid=351

- https://www.proquest.com/hnpchicagodefender/historical-newspapers/hits-at-regal-theater/docview/492377702/sem-2?accountid=351

- https://www.architecture.org/online-resources/buildings-of-chicago/new-regal-theater

- Semmes, Clovis E.. The Regal Theater and Black Culture. United Kingdom, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/319