The exhibition piece, Prayer for Peace, describes Kurt Westerberg’s ‘72 De Profundis, and the images reflect a powerful response from St. Olaf students to the tragic events at Kent State and Jackson State Universities in 1970. De Profundis, which translates to “out of the depths,” was composed by Westerberg as a sophomore in the wake of these violent events, where students lost their lives amidst the turmoil of Vietnam War protests1.

The images above capture the performance of De Profundis on Capitol Hill in May 1972. This twenty-minute, three-movement composition combines vocals, instrumentals, and dance to express grief, reflection, and a longing for peace. In the program introduction, Westerberg wrote, “De Profundis is not meant to be entertaining listening nor is it a ‘hip’ version of a Biblical Psalm2.” This is important to note, given the importance of the piece’s expression.

Image of Dell Grant ‘73 – St. Olaf’s First African American art major, who choreographed the sequence and performed alongside 18 others at the Capital Hill performance in 1972

Westerberg based the piece on Psalm 130, a text he encountered during a memorial service honoring the victims of the protests. The Psalm’s lines,

“If you, Lord, kept a record of sins, Lord, who could stand? But with you there is forgiveness, so that we can, with reverence, serve you3.”

form an emotional heart of De Profundis. By setting these words to music, it seems Westerberg aimed to transform sorrow and lament into a communal prayer for reconciliation, contrasting the bitterness of violence with a desire for forgiveness and healing.

While looking more into De Profundis, I came across a transcript of an interview with Westerberg in 2013. In response to his recalling of the Washington D.C. experience, he reflected on the growth of the piece and its communal contribution, stating the following:

“It was a very humbling experience to have my sophomoric work used to express a significant desire for peace and reconciliation. It was really not just my work anymore – I knew that it had grown beyond my creative input, and had impact because of the result of so many other efforts, including the [singers], musicians, and dancers4.”

As I reflect on this composition and the images, I am reminded of Nina Simone’s Mississippi Goddam, written in response to the bombing that killed four Black girls in Birmingham5. While both Westerberg and Simone address violence, their approaches differ. Simone confronts institutional racism with urgency, her music demanding justice. In contrast, Westerberg seeks solace, inviting spiritual introspection as a response to tragedy.

De Profundis, therefore, stands as a testament to music’s power to respond to violence in varied ways, whether by seeking peace, demanding change, or gathering a community in shared reflection.

1 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

2 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

3 New International Version, 2011. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%20130&version=NIV.

4 Sauve, Jeff. “A Musical Prayer for Peace.” St. Olaf Magazine no. Winter, 2013.

5 Fields, Liz. “The Story behind Nina Simone’s Protest Song, ‘Mississippi Goddam.’” PBS, June 30, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/the-story-behind-nina-simones-protest-song-mississippi-goddam/16651/.

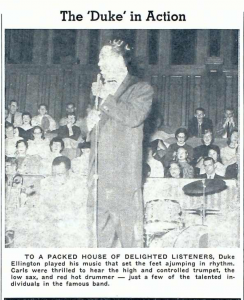

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

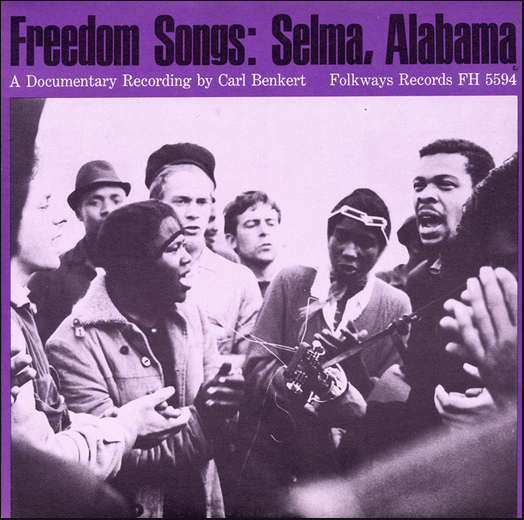

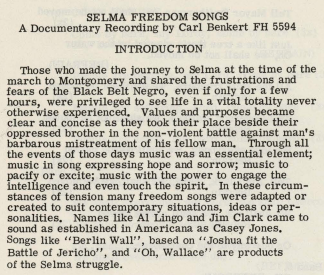

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

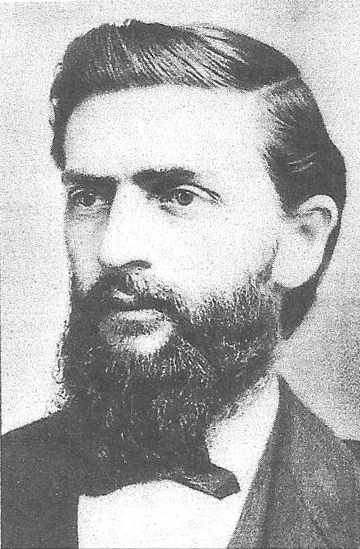

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

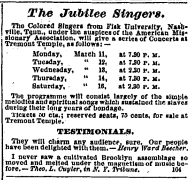

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

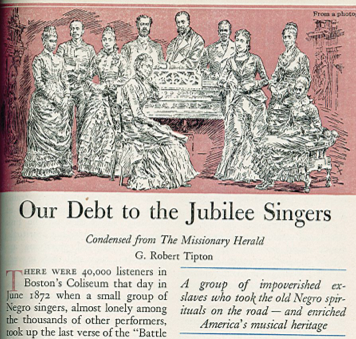

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.