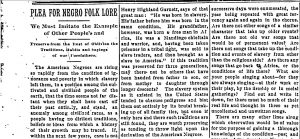

After searching a bit on the database, I stumbled upon a document called, “Plea for Negro Folk Lore,” published as the Freeman on January 27, 1894. In this article, author Miss A.M. Bacon argues that within a handful of years as of the publishing of this article, the history of black Americans would dwindle, and be reduced to nothingness-completely assimilated into society with no traditions, beliefs or ideas from the past. The thought that the new generation was not aware of the sufferings of their ancestors is frightening. To combat this rising problem, the author suggests the history of black Americans, specifically enslaved black Americans to be meticulously collected. Likewise, she argues that such knowledge must be collected by intelligent and educated black scholars in order to accurately inform from their own experience. Bacon numbers the types of information that must be collected: Folktales, customs, traditions, African words surviving in speech or song, ceremonies and proverbs. Through collecting these items, the history of black Americans can be compiled, so that everyone knows the struggles of the past.

into society with no traditions, beliefs or ideas from the past. The thought that the new generation was not aware of the sufferings of their ancestors is frightening. To combat this rising problem, the author suggests the history of black Americans, specifically enslaved black Americans to be meticulously collected. Likewise, she argues that such knowledge must be collected by intelligent and educated black scholars in order to accurately inform from their own experience. Bacon numbers the types of information that must be collected: Folktales, customs, traditions, African words surviving in speech or song, ceremonies and proverbs. Through collecting these items, the history of black Americans can be compiled, so that everyone knows the struggles of the past.

One of the best ways to explore the past of black Americans is through the surviving words through speech and song. While people had recorded spirituals at the time, Bacon focuses on different kinds of songs. She references utterances, both musical and rhythmic. Further on, she poses the question to her audience of primarily black Americans, “What are your people singing about – for they are always singing – at their work or their play, by the […] or in social gatherings?”1 Bacon presents a clear call to action to notate such music, as it is these songs that contain the history, life and identity of the black American.

Of course, it is our job and duty as musicologists to collect the history of music, but also to respect the cultures which we are observing. This article describes an issue of the past, but its effects are still felt today. The author asks black Americans to collect said data on their culture, history and music rather than white Americans. This is an ask on authenticity, and what is truly authentic. Personally, I think the most important part of any data collection is consent. The second is avoid cultural appropriation when possible. The fear that white people would culturally appropriate black culture was a fear then and continues to be a fear today. In fact, the conversation of cultural appropriation is a wide and winding one. The shades of grey cannot be less defined. I have my own definition, which looks at intent and outcome. If either category is not right, then there is cultural appropriation. Is the data collector (in this case, musicologist) going in with the intent to capture a culture and keep as much authenticity as possible? Are they doing so to publish a book, or to take inspiration? Do they have the consent of the culture to gather the data? The line between cultural appropriation and appreciation is thin and narrow and can completely reshape the way people view said culture, people, and the recorder of the data itself.

1 “Plea for Negro Folk Lore,” page 2, column 3, line 11-15

“Plea for Negro Folk Lore.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana) 6, no. 4, January 27, 1894: [2]. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANAAA-12C8A12E849E6750%402412856-12C8A12E9A8258B0%401-12C8A12F1D93D6A0%40Plea%2Bfor%2BNegro%2BFolk%2BLore (Accessed October 12th, 2022).