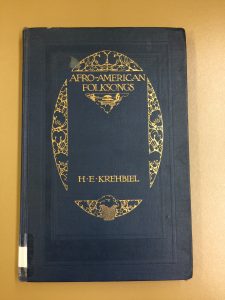

When reading selections from Henry Krehbiel’s 1914 publication of Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music,1 Music 345 was perplexed to compare his eagerness to embrace African American folksongs as American creations attributed to Black people in America to the writings of George Pullen Jackson in White and Negro Spirituals (1943). 2There was a general consensus among us that as history progresses, so do our politics. So I want to know: what was Krehbiel inspired by, and what can his background tell us about his research and publications?

I do not seek to answer this question in full with a blog post, however I do think it is worthwhile to consider where his inspirations came from. Henry Krehbiel was a first generation American growing up in a German speaking family. He started working for the New York Tribune around 1880 and soon rose to the title ‘music editor’ which gave rise to his writings on American music. His 1914 publication cited above is said to be inspired by his attendance of the World Columbian Exhibition of 1893 in Chicago. The World Columbian Exhibition in Chicago was quite frankly a great show of American exceptionalism meant to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus in 1492 featuring over 200 buildings boasting neoclassical architecture as well as artists and musicians, including African American music from the Dahomean village. 3

First page of the program for the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago, 1893.4

The very music Krehbiel heard from the Dahomean village at the World Columbian Exchange inspired the musical, In Dahomey, a piano-vocal score written by Will Marion Cook and vaudevillians Bert Williams and George Walker. According to some sources, this was the first publication of its type and was performed over 1100 times in the United States and England from 1902-1905.5,7

Johns, Al, and Frank Saddler. In Dahomey. Sol Bloom, New York, NY, 1903. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100010193/.6

The history behind the Dahomey village as it existed in America has somewhat of a different origin story. The kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located in present day Benin that was colonized by the French, so many of the artifacts on display at the World Columbian Exchange were actually collected by the French Colonial Office during the scramble for Africa between 1880 and 1885.7 Knowing that the Dahomey village in America was the product of colonialism and that Krehbiel was probably enthralled in an exotic fascination of their music greatly informs how we think about his research. This being said, Krehbiel’s colonial bias does not detract from the impact of Dahomean music on American music as a genre. We must instead lend some more credence to the instrumental role African Americans played in creating the genre of American music.

Krehbiel’s interest in the music of the Dahomean village is somewhat analogous to Dvorak’s fascination with folksongs that inspired the New World Symphony which was also written in 1893. This work supposedly also contributed to his own research in gathering music from Americans and immigrants to study and write about. Knowing that Krehbiel, though not an anti-racist by any means collected his own research and information perhaps lends more credence to his work than Jackson who relies strictly on conjecture and other researchers.