The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was a law passed by President Andrew Jackson in order to, as the name of the law suggests, remove Native Americans from the areas east of the Mississippi River, and relocate them elsewhere. Notable images this invokes include the Trail of Tears and the Pottawatomie Trail of Death.

Thomas McKenney was the Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the time, helped to draft the Indian Removal Act, and a believer in the Native American “Civilization” program. He ran an experiment, hosting two young Native American men and allowing them to attend a white school. He reflected on his efforts in an 1872 publication of his book “History of the Indian Tribes of North America: With Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs”: “[…] in the attempt to civilise the Indian, a little learning is a dangerous thing, and that a half-educated savage seldom becomes an useful man. […] Unless he has the strength of mind to attach himself decidedly to one side or the other, he is apt to vacillate between employments of the white man and the Indian, inferior to both, and respected by neither.” (McKenney, 302). For this experiment, and general lack of harmony on the issue of Native American intelligence, he was dismissed by the Jackson Administration later that year.

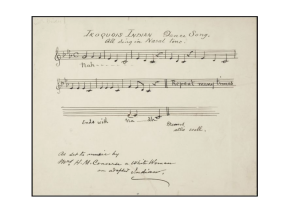

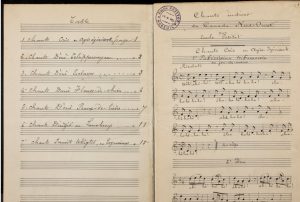

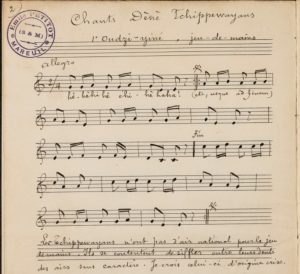

He was a profound believer in the “Myth of the Disappearing Indian”, the myth that Native Americans are mysteriously disappearing, so he collaborated with writer James Hall and painter Charles Bird King to create a collection of biographies, stories, and portraits from Native Americans. The myth resulted in many white Americans with some degree of power and no ethnological experience rushing out to record any amount of native culture they stumble upon. This sounds like a well-meaning effort, but neither one of the three were ethnographers, thus much of the text, especially involving the music and art that the Native Americans would create is not quite neutral.

“The music”, they write, “is a monotonous beating upon a rude drum, without melody or tune; the movements exhibit neither grace nor agility, and the dancers pass around a circle with their bodies uncouthly bent forward, as they appear in the print, uttering low, dismal, syllabic sounds, which they repeat with but little perceptible variation throughout the exhibition.” (Mckenney 4). This hearkens back about three hundred years to when Sir Francis Drake described, upon meeting some of the first indigenous Americans, their music as “miserable” and “shreeking”, (Tick 6).

It’s possible that they created this collection not for the sake of preserving Native American culture, but rather to preserve their own senses of morality. While McKenney did preserve some stories and portraits of people at the time, he still perpetuated the idea that white people have to save this “endangered species”, while not condemning his own actions while in office or the actions of the government.

McKenney, Thomas, et al. History of the Indian Tribes of North America with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs. 1830. vol. 1, Philadelphia, PA, E.C. Biddle, 1838. Accessed 19 Sept. 2024.

Music in the USA : A Documentary Companion, edited by Judith Tick, and Paul Beaudoin, Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/stolaf-ebooks/detail.action?docID=415567.