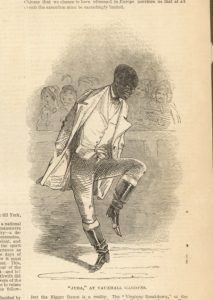

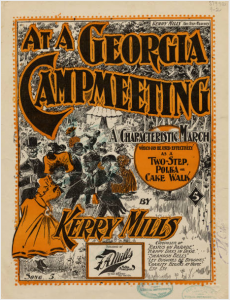

Minstrelsy is 1“the form of entertainment associated with minstrel shows, featuring songs, dances, and formulaic comic routines based on stereotyped depictions of African Americans and typically performed by white actors with blackened faces,” as defined by Oxford Languages.

Seeing the history of minstrelsy emerge in America beginning in the 1830’s in the Northeastern states was just another racist blow directed to people of color, specifically African Americans. The hatred was portrayed as a “national artform” expanding to even operatic shows by appealing to the intended white audience.2

It is also important to know that minstrelsy was not limited to only America, but Latin America was exposed to it as well. It can be observed that 1“American blackface minstrels began to perform for local audiences in Buenos Aires between 1868 and 1873” (Adamovsky, 2021).

The reasoning behind this takes into account the slave trade going mainly to parts of America and South America and spreading inward. The artforms of theatre, opera, and dance found a common ground for the white audience to ridicule the black folk regardless of if they were free or not. Thus creating a race barrier for any person of African descent living in the Americas since the emergence of minstrelsy and progress of slavery.

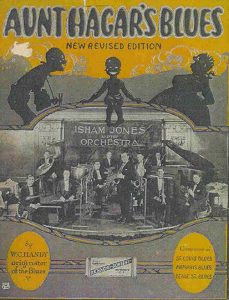

The incorporation of Shakespeare’s minstrelsy seen in the nineteenth century productions as well shows the crossing of time relative borders of racism and does not come as a surprise as it incorporated swing music and African American culture that was catered to the exclusively white audience. As continued in one of the productions Swingin’ he Dream, 3“the only hint of non-Anglo ethnicity is a Latin American chanteuse who plays the bad girl role of Kyser’s would-be seducer” (Lanier). The inclusion of people of color as the weaker party submissive to the white superior only ties back to the roots of slavery.4

1Adamovsky, Ezequiel. “Blackface minstrelsy en Buenos Aires: Las actuaciones de Albert Phillips en 1868 y las visitas de los Christy’s Minstrels en 1869, 1871 y 1873 (y una discusión sobre su impacto en la cultura local).” Latin American Theatre Review 55, no. 1 (2021): 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1353/ltr.2021.0027.

2Haines, Kathryn. n.d. “Guides: Blackface Minstrelsy Resources: Blackface in Other Cultures.” Pitt.libguides.com. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://pitt.libguides.com/c.php?g=935570&p=6831076.

3Lanier, Douglas. 2005. “Minstrelsy, Jazz, Rap: Shakespeare, African American Music, and Cultural Legitimation.” Borrowers and Lenders I (1).

4McMains, Juliet. “Brownface: Representations of Latin-Ness in Dancesport.” Dance Research Journal 33, no. 2 (2001): 54–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1477804.