When we think of the term “looney”, many of us envision the literal definition – silly, strange, or funny. Others align the word with the beloved cartoon series, “Looney Tunes”, a film series of charming cartoon characters (Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, etc) that originally ran from 1930-1969 during the “Golden Age” of American animation. However, in the context of late 19th-early 20th-century minstrel shows and entertainment, “looney” was used frequently to describe the personalities of African-Americans, as portrayed by black-face minstrel performers. What made African Americans “looney” in black-face minstrelsy? This question invites a deeper discussion into how the term was used to reinforce harmful stereotypes through exaggerated performances, ultimately shaping societal perceptions and contributing to a legacy of racism in American culture.

After scouring the Sheet Music Consortium database, I came across a solo piano repertoire piece that raised my eyebrow entitled “Looney Coons”. The piece, published in 1900, is a short solo piano repertoire work composed by John T. Hall. Hall, born John T. Newcomer in 1875, Hall experienced success relatively early with his waltz “The Wedding Of The Winds”, which is still his most famous work today. Later in life, Hall was involved in a scam using the business name Knickerbocker Harmony Studios, where he falsely advertised prizes for song contests, while only offering the submitters help in publishing their songs — for a fee. For this, Hall was convicted and sentenced to two years in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta.

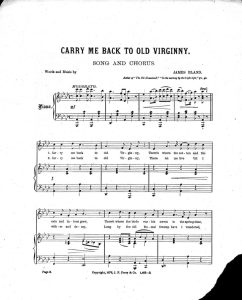

Cover page of “Looney Coons: Cake Walk & Two Step”, a solo piano work composed by John T. Hall in 1900.

Hall didn’t compose many works, but “Looney Coons” is one that did not age well after the black-face minstrel period was surpassed. While the composition itself seems tame, the title page cover showcases off-putting imagery of four black-face minstrel figures happily galivanting, dressed in affluent garb that was commonly worn by upper-middle-class white audiences. The title, “Looney Coons”, is sprawled across the cover in garish, yet eye-catching font, with the supplemental text reading “Cake Walk & Two Step”. The cakewalk was a dance form that became popularized before the United States Civil War originally performed by slaves on plantations. Lakshmi Ghandi states on NPR, “Plantation owners served as judges for these contests — and the slave owners might not have fully caught on that their slaves might just have been mocking them during these highly elaborate dances”. While “Looney Coons” may reflect a specific historical context, the imagery and title evoke deeply troubling emotions, revealing how entertainment can perpetuate harmful narratives, especially in minstrel shows.

Upon reviewing “Looney Coons”, my observations draw me back to the conversations we had in class about black-face minstrelsy. Through this performance practice, African Americans were painted in a harmful, stereotypical light that perceived them as lazy, unintelligent, and, namely, looney. Hall’s decision to publish black-face minstrel imagery for a piano work entitled “Looney Coons” not only perpetuates a legacy of racism in American culture but also reinforces the idealogy of African Americans being lesser. “Looney Coons” reflects the troubling legacy of minstrel shows, urging us to confront harmful racial stereotypes in music.

WORKS CITED