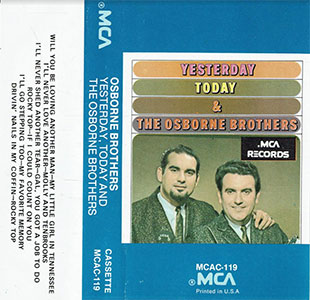

In March of 1969, the Osborne Brothers, a bluegrass duo from Kentucky, released a record called “Yesterday, Today and the Osborne Brothers.” The album was half vintage, half contemporary bluegrass tunes, including re-recordings of the duo’s greatest hits. The same month, a review of this album appeared in The Minority Report, which was an underground African-American newspaper based in Dayton, OH. The reviewer, Mike Hitchcock, was writing during the time of the folk revival of the mid-20th century, and he notes this in the opening paragraph:

“The latest issue of Rolling Stone…is chock full of stuff about bands like Pogo,…Crosby, Nash and Stills, and the word from people on the West Coast is that country music is rapidly becoming where it is at.”1

Hitchcock does clarify, though, that he doesn’t believe the Osborne Brothers are “happening” yet, and are rather on their way to reaping the benefits of this folk revival.2 The review is framed as an early discovery of this up and coming group (though they had been well established in bluegrass as a genre), and credits the largely black readership of the newspaper with being a driving force in a bluegrass revival, due to the genre’s roots.

Cover of ‘Yesterday, Today & the Osborne Brothers’

One of the main ways Hitchcock does this is through his emphasis on the live performance aspect of the genre of bluegrass. He recounts how one of the more traditional songs on the record is “the kind of thing you used to hear at the Ken-Mill when all the boys were too drunk to fight anymore and not drunk enough to go home and somebody would put a quarter in the request box…”3 Demonstrating the community aspect of this genre is how Hitchcock asserts it as popular and integral for his reader base, which are largely Black Midwesterners.

His focus on the communal roots of bluegrass music being evoked through traditional songs that are recorded for a commercial audience contrasts the condescending reaction to bluegrass from the wider public that he observes. The example given by Hitchcock involves general condescension at the University of Chicago Folk Festival, where bluegrass was described as “quaint and ethnic.”4 To Hitchcock, this is precisely the reason that although they are making progress towards popularity, bluegrass musicians are still largely not considered “hip.” He directly ties this to the socioeconomic and racialized origins of bluegrass when he asks the rhetorical question: “After all, what do [n-words] and hillbillies know about music?”5

In addressing the fact that bluegrass is a music traditionally enjoyed and made by Black people and poor White people, and yet is on the rise in universal popularity contrary to previous resistance at the idea, Hitchcock is documenting an important cultural dialogue around folk and popular music. We now craft arguments such as his to give equal stake in the popularity and commercial uses of bluegrass to all who were/are the originators and curators of the genre.

1“The Osborne Brothers. Buy a Nickel of Bluegrass Baby.” Minority Report (Dayton, Ohio) 1, no. 4, March 15, 1969: 5. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12A7ECD8048E2975%40EANAAA-12BA755320D4E840%402440296-12BA7553513015E0%404-12BA7553CDFFFFE8%40The%2BOsborne%2BBrothers.%2BBuy%2Ba%2BNickel%2Bof%2BBluegrass%2BBaby.

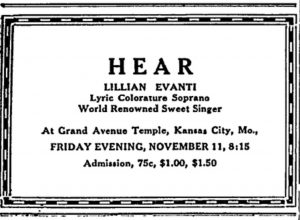

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)