The caricature of the savage Native American is all too common in the history of American Art. This is especially true in art of the American West, rife with its depictions of pioneers and cowboys fighting off Indians and the elements in the name of survival and Manifest Destiny.

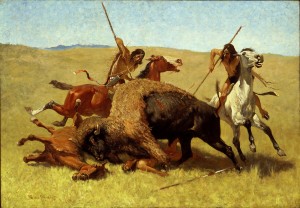

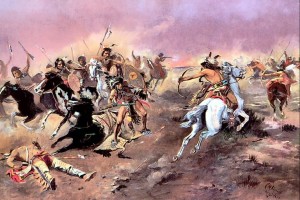

Some turn of the century artists like Charles Marion Russell (1864-1926) and Frederic Remington (1861-1909) managed to rehabilitate this image, depicting ways in which Native Americans (and men in particular) could be pleasant to look at artistically. In the masculine world of the West, this primarily meant depicting them as active participants in the drama of uncharted territory. However, this also reinforced the notion that American Indians led a violent, uncivilized life.

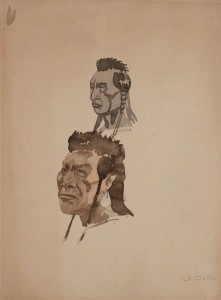

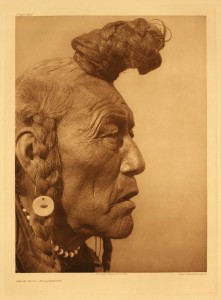

This serves as a marked contrast to the Native American Portrait Study by Olaf Carl Seltzer (1877-1957) in the Flaten Art Museum Collection. The first word that came to mind when I saw it was ‘dignity’; the second was ‘still’.

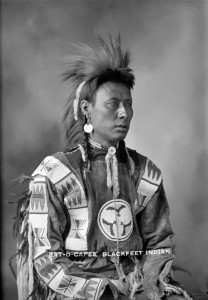

Seltzer lived in Great Falls, Montana from the time he was 19 until his death. From that, I inferred (with the consultation of a map of Native American tribal territories) that this study is of individuals belonging to the Blackfoot tribe. A simple google image search confirmed this suspicion, as I found numerous portraits of Blackfoot members whose hairstyles and earrings strongly resemble those in the study.

Of course I don’t mean to suggest through this analysis that the Blackfoot people or any other group of Native Americans needs a white man to recapture their dignity. But it is refreshing to see that there is at least one instance in American art of someone capturing the dignity of Native Americans authentically not through violence, but through still portraits. Even if it is just a study.

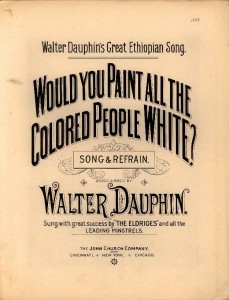

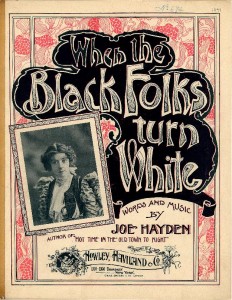

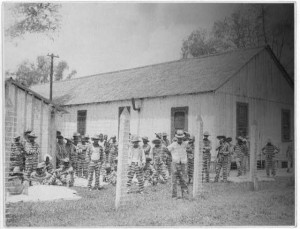

In studying the history of American music, we have seen multiple times how non-white cultures have been repeatedly misrepresented. The violence latent in portraits by Russell and Remington can be found in stereotypical musical depictions of Native Americans that rely on similarly simplistic and vulgar generalizations: I’m thinking especially of pulsing drums, war-whoops, and melodies that only use pentatonic scales.

Even recent depictions rely on the simplistic drum patterns and repetitive melodies that have been stuck to Native American’s since the beginning, even when the atmosphere isn’t as frenetic, violent, or (in the case of Peter Pan) partially sexualized.

Who then is the Seltzer of American music? In other words, is there anyone that we can point to as capturing the essence of Native Americans without cheap theatrics? Perhaps the closest is Edward MacDowell’s Indian Suite (1892), which utilizes (alleged) Native American melodies. Luke provides an excellent study of this depiction here.

The unfortunate truth remains that we are relying on inauthentic depictions of Native Americans by whites to explore Indian-ness. But isn’t to say that there aren’t any Native American composers trying to do the same; a simple YouTube search shows otherwise. Unfortunately, these composers don’t hold a firm place in the current music history curriculum. While articles like this are a start, we as musicologists must strive to support authentic depictions of Native American music while remaining critical of the Russell’s and Remington’s of American music.