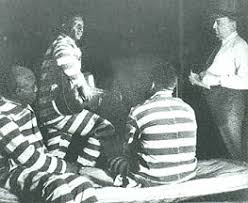

This video shows John Lomax collecting songs in the Louisiana from a black prisoner named Lead Belly. This video is a good representation of part of what went into collecting and preserving folk music. We also get a good look at the differences in power and how race plays into that.

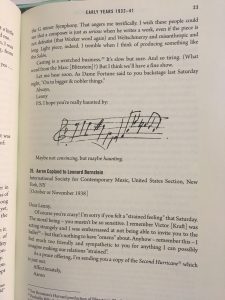

John Lomax is known for his work in the field of folk musicology, and we can be grateful for his work. The Lomaxes have been recognized for their contributions. John Lomax influenced the repertory of folk music that helps define American folk music, and he also helped establish Leadbelly who, along with other artists, helped pave the way for future artists and genres such as rock music. Yet, it is important to remember the way in which the Lomaxes impacted folk music. Their goal was not only to preserve, but to popularize folk music, too. They specifically picked songs that matched this agenda. Once they were recorded, they were preserved and created into a history by design.

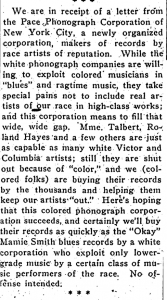

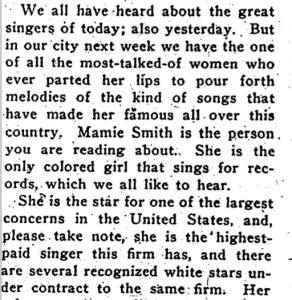

Once Lead Belly was released from prison, he continued working with the Lomaxes in order to advance his career outside of prison. Lomax’s praise of Lead Belly’s songs, can be heard in the video; “I never heard so many good negro songs.” Yet, Lomax often presented a romanticized view of the hardships that African Americans went through. Lomax made sure that Lead Belly would perform in his prison uniform, even during the time after his release. Lead Belly was also advertised as being dumb and violent, despite his gentle nature. The Lomaxes were able to get away with presenting a kind of folk music that they thought would beat the commercial tendencies of the time at the expense of black folk artists like Lead Belly.

Once Lead Belly was released from prison, he continued working with the Lomaxes in order to advance his career outside of prison. Lomax’s praise of Lead Belly’s songs, can be heard in the video; “I never heard so many good negro songs.” Yet, Lomax often presented a romanticized view of the hardships that African Americans went through. Lomax made sure that Lead Belly would perform in his prison uniform, even during the time after his release. Lead Belly was also advertised as being dumb and violent, despite his gentle nature. The Lomaxes were able to get away with presenting a kind of folk music that they thought would beat the commercial tendencies of the time at the expense of black folk artists like Lead Belly.

“Leadbelly” in March of Time, Volume 1, Episode 2 (New York, NY: Home Box Office, 1935, originally published 1935), http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C1792710

Filene, Benjamin. “”Our Singing Country”: John and Alan Lomax, Leadbelly, and the Construction of an American Past.” American Quarterly 43, no. 4 (1991): 602-24. doi:10.2307/2713083.