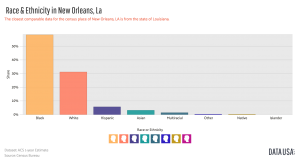

““It ain’t what it was,” the old folks say, but New Orleans jazz is still better and more boisterous than you get served and verve up to you anywhere else.”

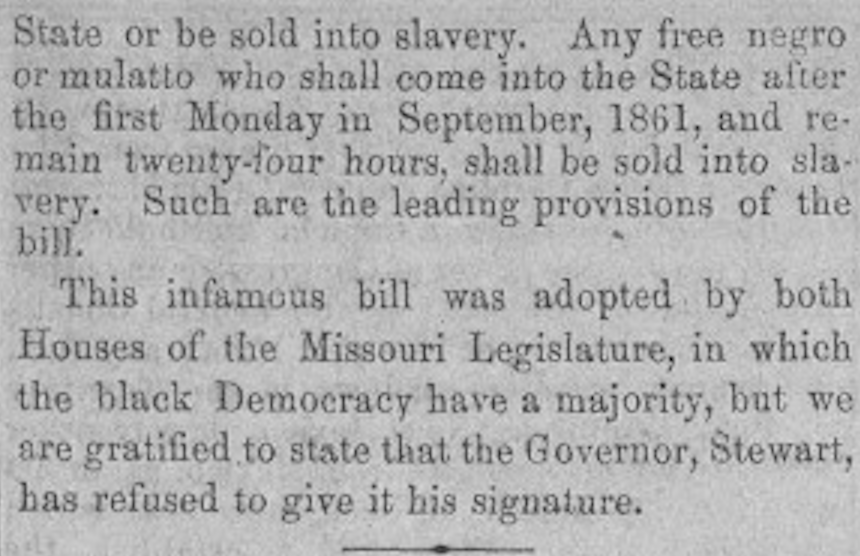

As early as the pre-civil war days, New Orleans residents played jazz and the blues. One big contribution to this celebration of music occurred when a group called the Carpetbaggers came to town. “They were hated by the local French whites, but loved by the local jazz players because they kind of “went for” the music. Word spread about the amazing, unique sounds of the Carpetbaggers all along the Mississippi River. As time passed, and music spread further, a business-man from out of New York City came along and signed the Carpetbaggers to a contract, spreading the blues from beyond the South. And the rest is history.1

New Orleans Blues and Jazz Band (Buddy Bolden’s, back row, center left, Band), 19056

The Mississippi River played a massive role in continuing the Black American tradition of jazz and blues music. “The famous U.S. Highway 61, known as the “blues highway” rivals Route 66 as the most famous road in American music lore. Dozens of blues artists have recorded about Highway 61.” A popular theme of these songs include the “pack up and go” mindset: leave troubles behind to seek out new opportunities, which is what many musicians decided to do. The original road traveled through and/or near cities such as Baton Rouge, Cleveland, Memphis, St. Louis, and Chicago to name a few. What do these cities have in common? They all continued to spread the love of blues and jazz music.2 Music in California, Chicago, and New York, were leading contributions to the birthplace of big time band leading, where larger ensembles with more orchestration began to grow.3

As jazz and blues music grew nationwide, the question at hand was if the spread of music was in honor of the tradition, or if the spread of music was in hopes to gain popularity both in the style and its musicians, further classifying this music as “popular music.” Bruce Jackson explains The American Folksong Revival in Jeff Todd Titon’s “Reconstructing the Blues: Reflections on the 1960s Blues Revival (Page 73): “Many writers and festival fans claimed the revival provided an opportunity for millions of modern Americans to better understand their country’s musical roots, as well as an opportunity to honor the musicians who still represented those traditions. Others–often disparagingly referred to as “purists” –were certain the revival and its attendant commercialism would provide the death stroke for whatever fragile rural and ethnic traditions still survived.”4

We, as musicians, can identify that most, if not all, different styles of blues music continued the legacy of its origins in two ways: (1) with the ever-present “blues scale” and (2) with the form, commonly referred to as the “12 bar blues.”

However, “Once Southern migrants introduced the blues to urban Northern cities, the music developed into distinctive regional styles, ranging from the jazz-oriented Kansas City blues to the swing-based West Coast blues. Chicago blues musicians such as Muddy Waters were the first to electrify the blues through the use of electric guitars and to blend urban style with classic Southern blues.”5

Even though these cities were introducing new populations to the origins of jazz and blues music, by the time these tunes were heard by audiences, they were drastically different from when they arrived. Another realization that I had when researching this topic was the fact that many blues composers would create their own melodies with the 12 bar blues form, but then would simply slap a location in the title, followed by blues, and call it good. New York City Blues, West End Blues, West Coast Blues, Statesboro Blues, Chicago Blues, St. Louis Blues, to name a few. Now where these titles meant to convey symbolic meaning by the composer? Or were these titles labeled to further gain popularity by the jazz and blues listeners of these respective locations? This isn’t a question that I can necessarily answer, but it brings up a great point: As we listen or play music such as the blues, are we interacting with the intent of acknowledging the history and origin, or are we interacting because it is catchy or popular? Is blues and jazz music considered folk music or popular music? Both of these questions don’t have right or wrong answers, nor do they have only one explanation. They do, however, require perspective when being placed in these conversations, and perspective requires more focus on the intention when engaging with these music styles.

1 Battelle, Phyllis. “How Jazz Music Migrated North and Captured Broadway’s Fancy: Oldtimer Tells ‘Woes’ of Men Who Pioneered.” Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), May 21, 1957, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/how-jazz-music-migrated-north-captured-broadways/docview/493656959/se-2 (accessed November 7, 2023).

2 “Highway 61 Blues.” The Mississippi Blues Trail, September 5, 2022. https://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/highway-61-north#:~:text=Some%20suggested%20that%20the%20road,journeys%20by%20continuing%20from%20St.

3 Roy, Rob. “Old Tymer Discovers Bop and Jazz Rooted at Base of Current ‘Raves’: Dixie Artists Hit N. Y. and Chicago Combining Styles.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 11, 1955, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/old-tymer-discovers-bop-jazz-rooted-at-base/docview/492899440/se-2 (accessed November 7, 2023).

4 Rosenberg, Neil V. “The Folksong Revival: Bruce Jackson.” Essay. In Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined. Urbana u.a.: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1993.

5 [Author removed at request of original publisher]. “6.2 the Evolution of Popular Music.” Understanding Media and Culture, March 22, 2016. https://open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/6-2-the-evolution-of-popular-music/.

6 “A New Orleans Jazz History, 1895-1927.” National Parks Service. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/jazz/learn/historyculture/jazz_history.htm.

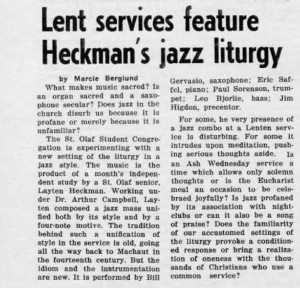

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]