William A. Pratt’s Following Up The Band: An African Sonata for Piano, published in 1900, presents an example of how African American influences were making their way into notated music 1.

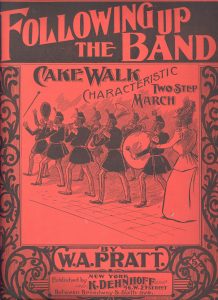

The piece, written as a piano sonata, mimics the sound of a marching band parading through the streets, taking on the style of a characteristic two-step march. The cover of the score, showing men in tailcoats and a woman in Victorian dress, shows imagery associated with the cakewalk, a dance that played a role in shaping early American music. This imagery, along with the music itself, suggests a blend of the social and cultural practices of the time.

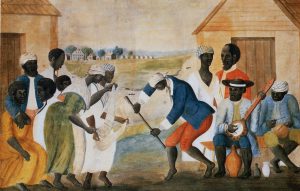

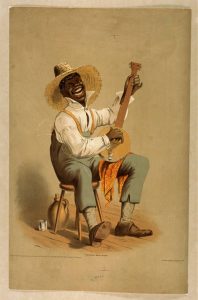

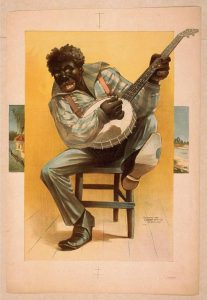

The cakewalk, a dance that was originally created to mock the European minuet, was adopted by Minstrel shows in the late 19th century. As John Jeremiah Sullivan points out, it began as a satire but was adopted by white performers as part of a caricature in their shows, creating a layered and looped irony: African Americans making fun of the minuet, and white people, in turn, making fun of the cakewalk2.

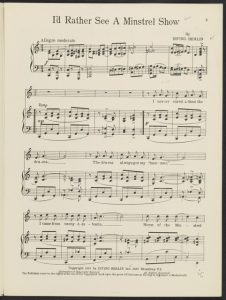

This irony, noted by writers like Amiri Baraka, reflects the complex relationship between African American culture and how mainstream society consumed it, particularly within minstrelsy3. Pratt’s African Sonata for Piano can be seen as part of this broader context. It combines the structure of a European sonata with a two-step rhythm that characterizes marching band music. I can not point to much syncopation or polyrhythms that would have been characteristic of a cakewalk, in the score, which makes me wonder about the performance practice for a sonata with the subtitle An African Sonata for Piano.

As we learn about the evolution of jazz, ragtime, and blues, the connection of the cakewalk becomes more apparent. Its influence on later musical forms is evident in works like Pratt’s, which, though written for piano, paints a picture of a marching band and the energy of a parade. The imagery on the score’s cover reinforces the connection to the cakewalk, reflecting the cultural dynamics of the time, both celebratory and ironic. This sonata serves as an example of how African American culture, despite being appropriated and caricatured in many contexts, was central to shaping later forms of American music as we know it.

1 William A. Pratt, Following up the band : cake walk characteristic two step march (New York, NY: K. Dehnhoff, 1900), accessed October 22 2024, https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sheetmusic/id/35013/rec/1

2 Sullivan, John Jeremiah. “‘Shuffle Along’ and the Lost History of Black Performance in America” New York Times. March 24, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/magazine/shuffle-along-and-the-painful-history-of-black-performance-in-america.html

3 Baraka, Amiri. Blues People: The Negro Experience in White America and the Music that Developed from it. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|452295.