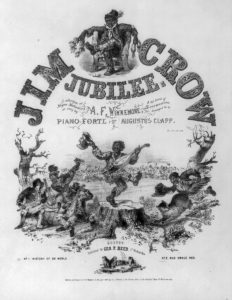

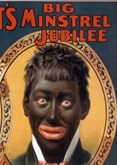

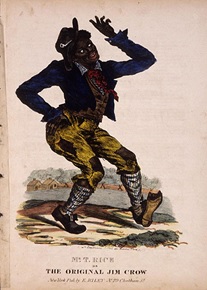

Defining American music. What is the definition of American music? There are several answers, it’s not quite black and white. Minstrel performances are one major “art form” that I believe influenced American music today.

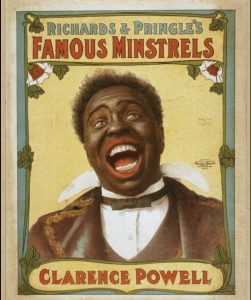

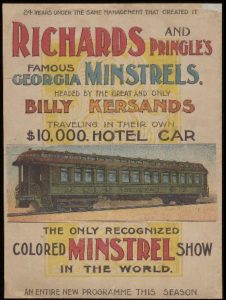

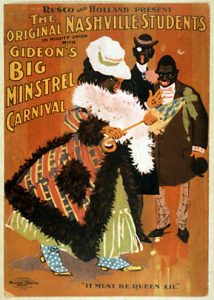

As is well known, minstrel shows performed by white people were designed to exploit and mock black people rather than to showcase their music. However, one could argue that black minstrel shows, such as Richards and Pringle’s Famous Minstrels, and minstrels in general could have influenced American music somewhat positively.

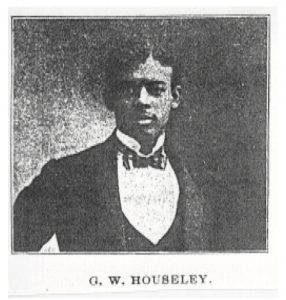

The two above images relate Richard’s & Pringles Famous Georgia Minstrels. Richards & Pringles Famous Georgia Minstrels was a black group of entertainers. They first started performing in 1879 and performed for over 20 years with on and off again conductor Frank Clermon. Golds W. Houseley became the conductor of Richards & Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels from 1898 to 1903. An accomplished musician and conductor, as in 1898, he became a solo cornetist for both band and orchestra for the John W. Vogel’s Concert Company which was considered the “best colored band in America” and more. 3

Such an accomplished musician participating in entertainment that previously had made fun of their own culture.

I believe that minstrel shows did help bring spirituals and folk songs to light, even how very controversial they were. One example is Golds W. Houseley. American music started to develop around 1920’s, especially with American and French Music. The National Association of Negro Music was organized in 1919. The goal was to stimulate, discover and foster talent, mold taste, promote fellowship, and advocate racial expression. 4

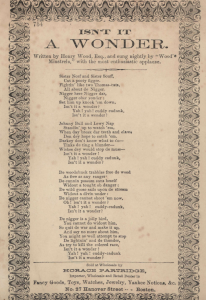

Stephen Foster was a white composer who merely imitated folk styles. He is given credit for implementing the romantic image of the Old South in American popular culture. He was the most popular product of the minstrel school of songwriters and continued to bring forward folk music to the classical world.

Will S. Hays is another prolific songwriter whose lyric themes are highly reminiscent of Stephen Fosters. The song “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” is a long staple of country music. It was also commonly heard in minstrelsy depicting sadness of a poor old slave.6

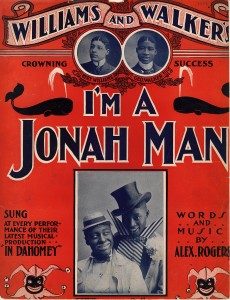

How racist and profitable minstrel shows were, they helped develop American music by bringing attention to them and their music.

1 https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/var.0233/

2Richards and Pringle’s famous Georgia minstrels : headed by the great and only Billy Kersands, traveling in their own $10,000 hotel car. (0 C.E.). [Advertisements, Hand coloring, Promotional materials]. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16700125.

3Schwartz, Richard I. “The African American Contribution to the Cornet of the Nineteenth Century: Some Long-Lost Names.” Historic Brass Society Journal 12 (2000): 75-76.

4 Samuel Floyd, Jr. “Introduction,” Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, 14.

5Schwartz, Richard I. “The African American Contribution to the Cornet of the Nineteenth Century: Some Long-Lost Names.” Historic Brass Society Journal 12 (2000): 76.

6Malone C., Bill, Stricklin, David. “Southern Music/American Music.” The University Press of Kentucky. 2003. Pg. 23-24.