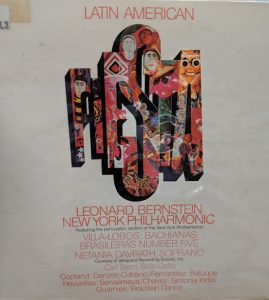

I found this LP in the Halvorson Music Library collection. If you look closely, you might be surprised to see Aaron Copland listed as one of the featured composers on this album. In class we talked about other instances of Copland drawing inspiration from the folk music of Latin America, but I didn’t expect his music to be set alongside the music of artists from Mexico, Brazil and Portugal, like it is in “Latin American Fiesta”.

While I find essentialism problematic in its own right, I have a hard time accepting Copland’s music into the genre of Latin American music, seeing as he is not a Latin American composer. I find his inclusion on an album of Latin American music problematic due to his position as an outsider of the musical tradition he is emulating as well as his place of privilege in the world classical music. I see this as an instance where the white perspective wasn’t necessary, but was nonetheless held to an equal, if not higher importance than the perspective of those within the musical culture the album was highlighting.

More of these instances can be found on the back of the album cover, where conductor Leonard Bernstein comments about the “Latin American spirit”. His exoticising of the music of Latin America as a blend of Native American and African music invalidates the genre as it’s own unique musical culture:

The sweet, simple primitiveness of the Indian music mixes with the wild, syncopated, throbbing primitiveness of African music; and both of these, mixed with the fiery flash of Spanish music and the sentimental sweetness of Portuguese songs, make up the music we know as Latin American.

While the inclusion of Copland and Bernstien’s views on Latin American culture are indicative of the ways the white perspective was favored in classical music, pieces like Bachianas Brasileiras, or “Brazilian pieces in the manor of Bach”, show that composers within different musical cultures were also being held to the standard of European classical music, and were changing their sound to fit a narrow mold reinforced by the educated, white, European and masculine standards set for classical music at the time.

While it is easy to see albums like this and think about how far we’ve come in, the failure to recognize the Latin American perspective is a more current issue than many realize, especially at St. Olaf. In the 1989 Manitou Messenger article Olaf missing Latin American view, student Julia Kirst speaks about the struggles of being the only international student from all of Latin America, as well as the positives of celebrating diverse experiences. I believe that providing a platform for people to share diverse experiences is the first step, and while the intentions of “Latin American Fiesta” may have been to provide such a platform, such intentions were undermined by the voices and perspectives they chose to include on the album.

Works Cited:

Davrath, Netania, et al. Latin-American Fiesta. Columbia, 1963.

Kirst, Julia. “Olaf Missing Latin American View.” The Manitou Messenger, 3 Nov. 1989.