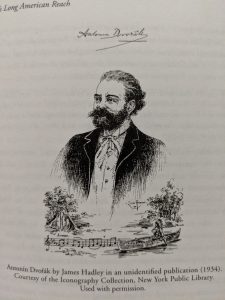

I found a book in Halvorson Music library called Dvorak in America: 1892-1895, which is a great resource for anyone wanting to learn more about the New World Symphony or other works of Dvorak’s that were influenced by the pursuit of creating “American” music.

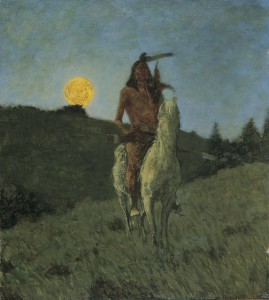

An image of Dvorak over a Native American rowing a boat. Tibbetts, John C. Dvořák In America: 1892-1895. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1993.

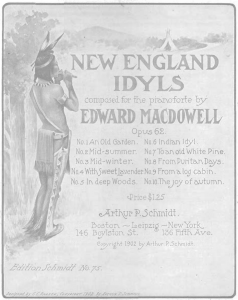

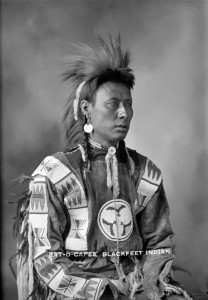

I was surprised to find what I assume to be a promotional image depicting Dvorak overlooking a Native American rowing a boat down a river of music notes in this book. In class we focused on McDowell’s attempts to tap into the music of Native Americans to find sources of inspiration for his American music and Dvorak’s attempts to do the same through spirituals. While Dvorak did search for inspiration for the New World Symphony in African American spirituals, “accompanying the premiere, Dvorak penned an essay in the New York Herald… now suggesting as well Native American melodies for that same purpose…. Dvorak’s suggestion of Native American music were largely overshadowed at the time by his assertion of African-American musics. But not long after Dvorak’s pronouncement, a so-called “Indianist” movement had emerged, placing Native American subjects at the fore of US musical nationalism.” [1]

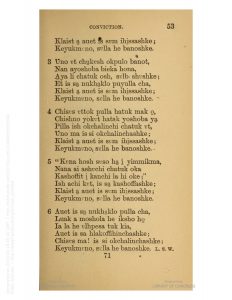

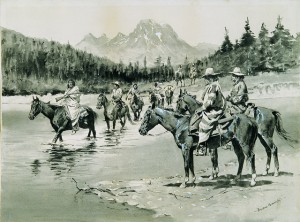

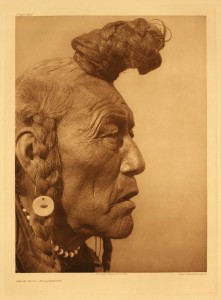

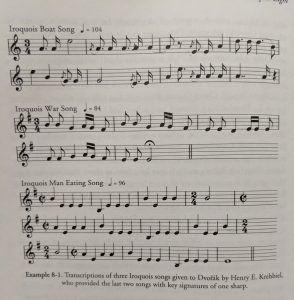

Transcriptions of three Iroquois songs given to Dvorak by Henry Krehbiel. Tibbetts, John C. Dvořák In America: 1892-1895. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1993.

I found it incredibly interesting to see Dvorak’s interactions with many of the notable names from our course. There’s a section on how Henry Krehbiel (questionably) transcribed some Iroquois melodies for Dvorak to take inspiration from in his New World Symphony and was clearly disappointed that he didn’t use them. When reviewing the work as a whole and finding an insufficient amount of ‘Indian spirit’, he decided that the work was not American enough and that “Dr. Dvorak can no more divest himself of his nationality than the leopard change his spots.” [2]

Since our class discussions are ordered based on musical genre rather than chronological order, it was really interesting and informative to see the interactions between all of the people and ideas involved and how they overlap. For those who want to learn more about the New World Symphony, Dvorak’s varying inspirations for music making and his interactions with other notable musicians and critics, Dvorak in America: 1892-1895 is a great resource and an interesting read.

_____

- Daniel Blim, “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians,” paper delivered at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society, Vancouver, BC, November 4, 2016.

Works Cited:

Daniel Blim, “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians,” paper delivered at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society, Vancouver, BC, November 4, 2016.

Tibbetts, John C. Dvořák In America: 1892-1895. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1993.