This painting found in the St. Olaf Flaten Art Museum suggests an immense feeling of age, wisdom, and timelessness. The subject, Walt Whitman, is presented in all shades of brown and grey, most of his body in shadow and the background irrelevant.

The artist, Xanthus Russell Smith, was known to be a Civil War Painter, showcasing the battles and details of wartime. But a quick search shows that he was also an avid landscape artist, portraying the lush beauty of the New England countryside in rich detail.

In fact, a closer look at the Whitman painting reveals more of the earthy tones of the artist. Whitman is not dressed for battle, but instead maybe for an introspective walk through the forest.

It is this sense of introspection that I would like to focus on. Many other art forms of the time, including MacDowell’s Woodland Sketches, also were introspective and communicated the viewpoint of the creator. Nature was a huge source of inspiration for these artists, as evident in Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road.”

“Song of the Open Road,” Walt Whitman

1

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

Henceforth I ask not good-fortune, I myself am good-fortune,

Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone no more, need nothing,

Done with indoor complaints, libraries, querulous criticisms,

Strong and content I travel the open road.

The earth, that is sufficient,

I do not want the constellations any nearer,

I know they are very well where they are,

I know they suffice for those who belong to them.

Nature provided the time and peace for artists to reflect upon their lives and their place in the universe. Their creations presented an individualized viewpoint of the world regardless of whether or not others understood. Smith’s painting showcases a man who knows all. And in his own particular way, Smith portrays how he sees Whitman, as all other artists share their specialized view of the world.

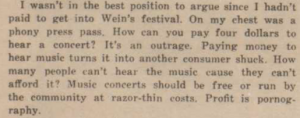

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.