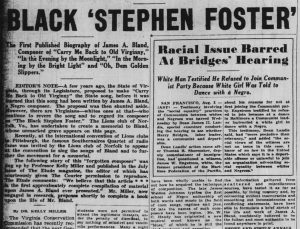

A headline from The Pittsburgh Courier (a Black newspaper) in 1939. The article is a biography of James Bland and is a response to the possible adoption of “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” as Virginia’s state song. Full page available here

TW: Racist descriptions of Black people

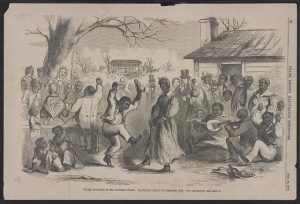

If you’re American, I’m willing to bet you’ve heard of Stephen Foster. Even if you couldn’t write a dissertation on him, there’s a pretty good chance you’ve heard the name, or sung one of his famous songs, like “Oh Susanna”. But have you heard of James Bland? Like Foster, Bland made his fame as a minstrel composer and was major player in the industry in the late 19th and early 20th century, yet Bland is far less known today. The difference? James Bland was Black.

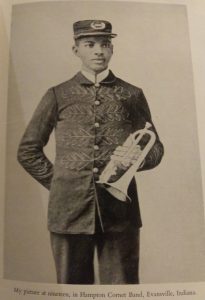

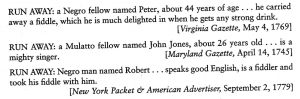

Bland was descended from a long line of free Black people (his father was educated at Oberlin College) and was born in 1854 in Flushing, New York. He was educated at Howard University. He was an extremely successful entertainer, having been part of many famous troupes, including as Sprague’s Original Georgia Minstrels and Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. And of course, he was also extremely successful as a composer. Though well known among those in the industry, Bland did not get the same recognition by the general public. He wrote over 700 songs, but only around 50 were published under his name. Some were even published under Foster’s, as Tom Fletcher, a contemporary of Bland, observed in his book 100 Years of the Negro Show Business:

“Both [Foster and Bland] flourished at the same time, during the early days of show business, but Foster’s friends and heirs kept his name before the public, a privilege Bland did not enjoy. The ideas of the two men on songs were very similar too, and very often a song written by Bland would be credited to Foster with whose name the general public was much more familiar.” (83)

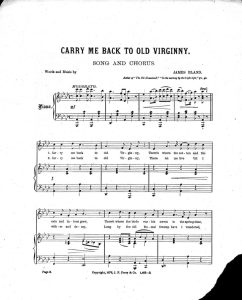

In fact, when “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” was proposed as the state song of Virginia in the late 1930s, many believed the song was written by Foster, and, according to the Pittsburgh Courier, when it was discovered to have been written by Bland, a Black composer, the proposition was almost discarded. It wasn’t, however, and Bland’s song was the state song of Virginia from 1940 to 1997, when it was removed due to its racist lyrics which sentimentalize slavery and the Old South.

A recording of “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” from 1916

James Bland in many ways encapsulates the tension inherent in bringing to light the accomplishments and successes of Black minstrel performers and composers in general. Many of Bland’s most famous works, like “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny”, have lyrics that romanticize slavery. Black minstrels sometimes both literally and figuratively had to “black up”, or in other words, cater to the white imagination of what Blackness really was. But it’s important to note that Bland also composed antislavery songs like “De Slavery Chains Am Broke At Last”, and had his own voice and agency – he was not merely an imitation Stephen Foster. And also, minstrelsy was one of the earliest opportunities for Black entertainers, performers, and composers to start their careers, to make make money, and to make their voices heard. What’s more, minstrelsy is far from gone in American popular culture. Which begs the question:

So long as we remember Stephen Foster, shouldn’t we remember James Bland too?

Bibliography

Bland, James A. Carry me back to old Virginny. John F. Perry & Co., Boston, monographic, 1878. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1878.x0004/.

Bland, James A, Orpheus Quartet, James A Bland, Josef Pasternack, Lambert Murphy, Harry Macdonough, William F Hooley, and Reinald Werrenrath. Carry me back to old Virginny. 1916. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-20049/.

Fletcher, Tom. 100 Years in the Negro Show Business. Da Capo Press. New York 1984.