Before we dive into Minstrel shows and what they exactly are, we should take a look at the history of the word “Minstrel” and its multiple meanings. I think it is important that we educate ourselves and others and learn the true history behind these shows and their meaning. In Hebrew, a minstrel is a player of a stringed instrument. There are references in the Book of Samuel of David as a minstrel playing for Saul.1

A little bit later, we find that a minstrel is a medieval poet and musician who sang or recited while accompanying himself on a stringed instrument, either as a member of a noble household or as an itinerant troubadour. As you can see, there are many different definitions of minstrel and how it truly hasn’t changed very much over many centuries. 2

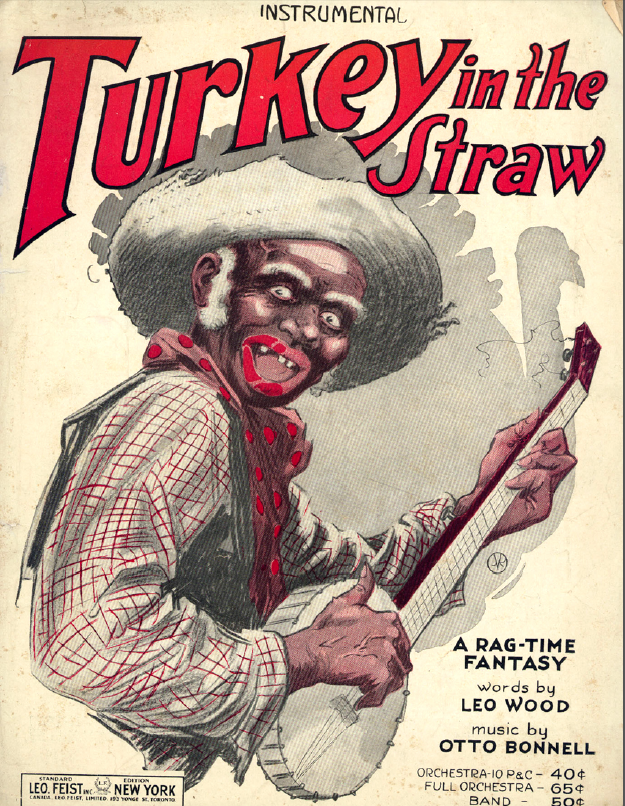

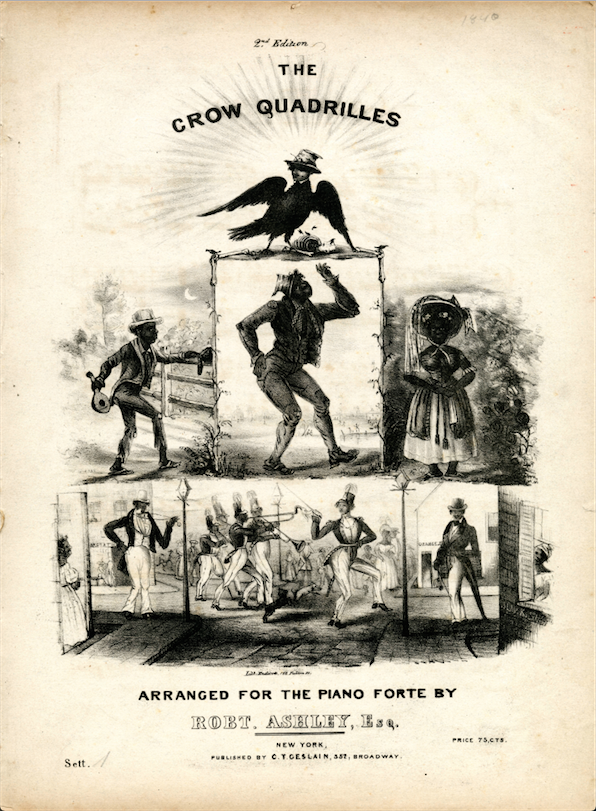

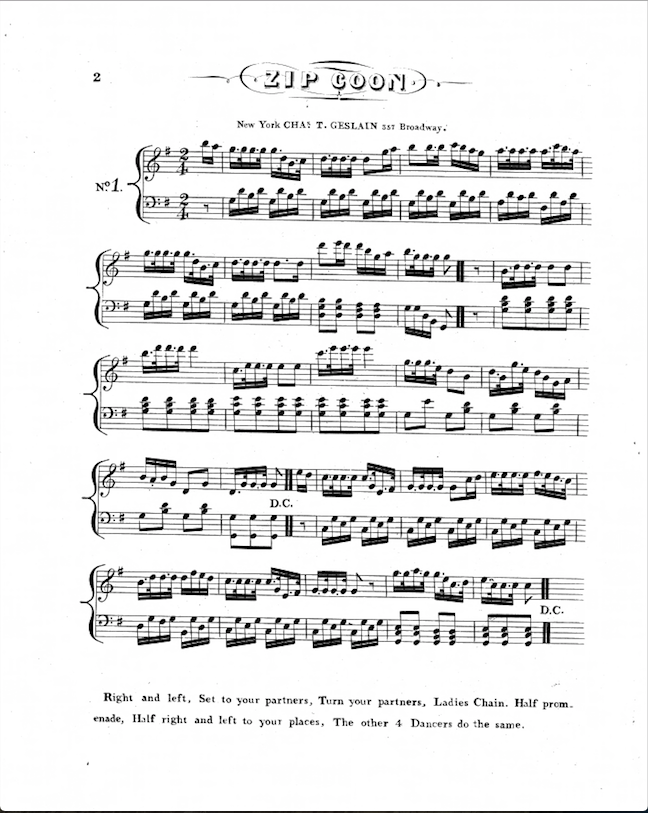

Then we reach the early 1830’s and we find that there are performances called Minstrel shows. “The first minstrel shows were performed in 1830s New York by white performers with blackened faces (most used burnt cork or shoe polish) and tattered clothing who imitated and mimicked enslaved Africans on Southern plantations. These performances characterized blacks as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, hypersexual, and prone to thievery and cowardice.” 3 It is important to note that when the word “Minstrel” originated, that person or persons were not being used to humiliate an entire race. We also need to be educated that the word “Minstrel” had not become popular with the definition of blackface until the 1800’s.

Continuing with blackface in the 1800’s, this small clip from a newspaper article in 1856 is quite the shocker. The parts that stood out to me were how “cheap” the entries to the shows were and that they essentially happened daily. The specific group that was performing that night were called the Campbell Minstrels and a few songs from their set lists include: “Darkies on the levee,” “Old Dan Tucker,” “Gold versus postage stamps,” and plantation scenes.