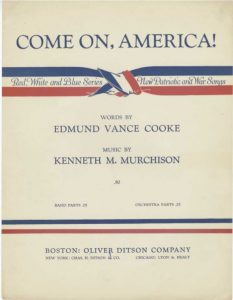

I seem to have a knack for digging up old American patriotic songs. In a previous blog post, I compared three sets of sheet music written between 1916 and 1918 and compared them to Virgil Thomson’s definition of musical traits post 1910. In the Latin American Experience database, I found a piece titled “The Yankee Message or Uncle Sam to Spain” by Edward S. Ellis and Chas. M. Hattersley. This one, however, was written in 1898, a full 20 years before “Come On, America” and its counterparts exemplified Thomson’s traits of 8th note continuity, separation between dynamics and tempo, and “phonetic distortion without loss of clarity.”

I seem to have a knack for digging up old American patriotic songs. In a previous blog post, I compared three sets of sheet music written between 1916 and 1918 and compared them to Virgil Thomson’s definition of musical traits post 1910. In the Latin American Experience database, I found a piece titled “The Yankee Message or Uncle Sam to Spain” by Edward S. Ellis and Chas. M. Hattersley. This one, however, was written in 1898, a full 20 years before “Come On, America” and its counterparts exemplified Thomson’s traits of 8th note continuity, separation between dynamics and tempo, and “phonetic distortion without loss of clarity.”

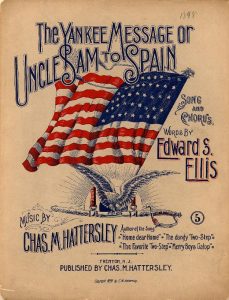

Like the other pieces, “The Yankee Message” is primarily in 2/4 with the eighth note driving the rhythm. The refrain is in 6/8 with alternating quarter and eighth notes. Syllabic text setting gives it a distinctly march-like feel, and dynamics and tempo are independent. The cover art features an American flag, and the “Yankee” title situate it firmly as patriotic

The date, title, and content leaves little guess work about the context of this piece. In 1898 the Spanish-American War began and ended in a matter of months. The most immediate and oft-pointed to cause of the Spanish-American War was the explosion of the USS Maine in 1898. However, the U.S. had long had interest in purchasing Cuba, and the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain was harming US monetary interests. After the Treaty of Paris concluded the conflict, Cuba gained independence, and the US received control over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

The date, title, and content leaves little guess work about the context of this piece. In 1898 the Spanish-American War began and ended in a matter of months. The most immediate and oft-pointed to cause of the Spanish-American War was the explosion of the USS Maine in 1898. However, the U.S. had long had interest in purchasing Cuba, and the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain was harming US monetary interests. After the Treaty of Paris concluded the conflict, Cuba gained independence, and the US received control over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

The lyrics of this piece read:

“1. I hear across the waters, From out the southern sea, The wail of sons and daughters, In wo[e]ful misery, If you must act the butcher, And helpless ones roust die, I swear by the Eternal! I’ll smite you hip and thigh!

2. We’ve got the boys to do it, A million men and more; We’ve got our new born navy, And Deweys by the score. We’ll smash your grim old Morroe[?], And brign them round your ears, And make the measure honest, With a thousand ‘Volunteers.

[Refrain:] Then hurrah, hurrah for Cuba! Our free Cuba.

We strike, we strike for wage and fight the battle. We strike, we strike for liberty! Until our Cuba’s free!

3. We greet you gallant Cubans, We’re fighting side by side, Not yet, O fair Antilles, Hath sleeping Freedom died; We’ll make that horde “walk Spanish,” (You hear my thund’rous voice,) And as between two evils, We’ll give you ‘Hobson’s choice.’

4. Our tears for the dead heroes, The Maine and martyred crew; A sigh for smitten sailors, Who died as patriots do; But sure as dawns the morrow, and sure as sets the sun, We’ll avenge our murdered brothers, Avenge them ev’ry one!

[Refrain]”

There’s a lot to unpack in the lyrics alone, especially as they are quite lengthy. The focus on freedom, liberty, and martyrs, suggest the war was fought for purely humanitarian reasons, a narrative the US government encouraged. Many phrases would require substantial investigation to understand from a contemporary perspective.

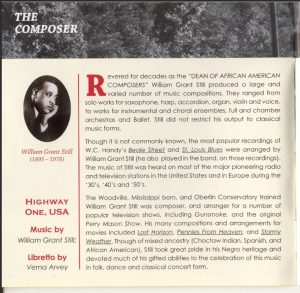

If the previous pieces I studied fit Thomson’s ideas to a fair extent, and this piece does as well, what does this say about American music? For one, perhaps identifying music after 1910 as distinct is not particularly helpful. Or, perhaps these pieces are more representative of a different genre, that of American patriotic marches. The design of the cover suggests Tin Pan Alley and pop music. Perhaps the exclusion of popular music was implied in Thomson’s writings. Regardless, examining patriotic music is helpful because these are the pieces that explicitly try to define themselves based on a national identity. From this we can gain insight into which common sonic features are thus implicitly “American” and recognize their significance when they appear outside of this context. This piece is also a great example of how current events routinely impact musical production. “The Yankee Message” is significant because it can be viewed as both a mirror to and an active participant in the discourse surrounding the Spanish-American War.

(Like my last blog post, I was unable to find a recording of this piece. Perhaps this calls for a recording session of American patriotic marches composed during war times?)

Works Cited

Hattersley, Chas. M. and Edward S. Ellis. “The Yankee message; Uncle Sam to Spain.” Trenton, New Jersey: Chas. M. Hattersley, 1898.

“The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War.” Hispanic Reading Room. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/intro.html.

Thomson, Virgil. “American Musical Traits.” American Music Since 1910. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.