Browsing through the Library of Congress National Jukebox, I came across a piece that had a curious title. “Shanghai lullaby” was composed by Isham Jones and published under Columbia records in 1923.1 The piece is listed as a foxtrot, which is a dance genre with origins in ragtime and jazz.2 When listening to the piece, you can hear the stylistic characteristics of the foxtrot from the beginning, such as a rhythmic emphasis on beats one and three and common jazz instrumentation.3 When I considered the title, I had anticipated that the piece would be full of painfully obvious appropriation and misrepresentation. To my surprise, much of the piece sounds quite tame in terms of musical markers of otherness. However, the title brings attention to the use of pentatonic melodic figures throughout the piece and sections that feature the distinctive and unexpected tone of the oboe.

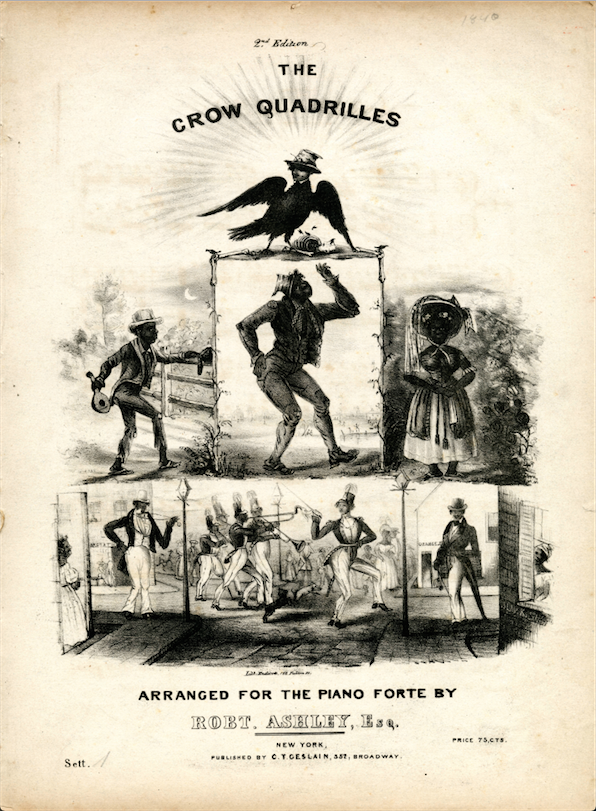

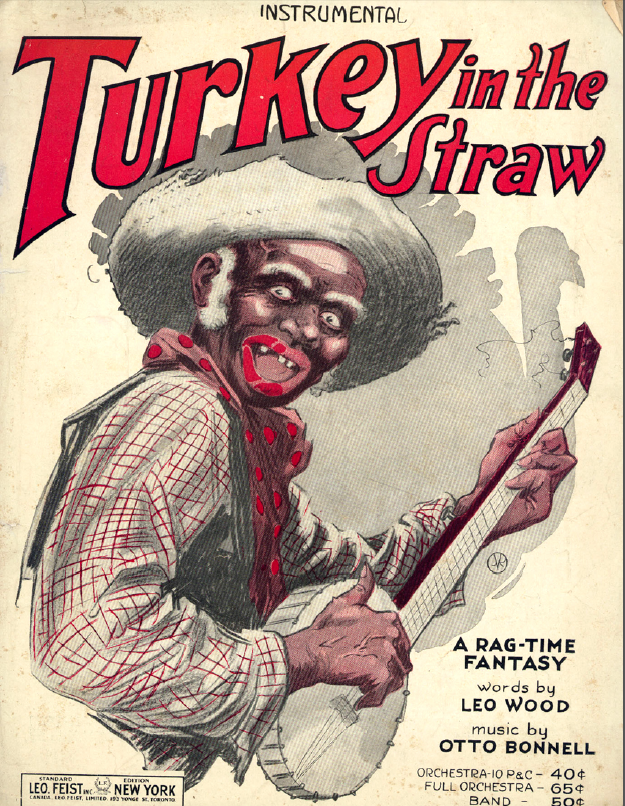

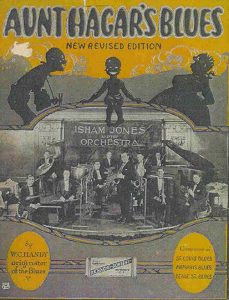

When considering cultural appropriation and misrepresentation, power dynamics cannot be ignored. “Shanghai lullaby” is a prime example of misrepresentation and appropriation of an other. Practices like this have a tendency to diminish a different group to nothing more than a few musical markers all for the sake of entertainment, interest, and novelty, which is a completely dehumanizing process. Unfortunately, using musical markers to profit off of marginalized groups was common practice during the period in which this piece was composed. A most notable example of this is Isham Jones and his Orchestra’s recording of “Aunt Hagar’s Blues,” which bears a cover featuring racist caricatures of Black Americans.4

Front page of sheet music edition of “Aunt Hagar’s Blues”5

Unfortunately, this piece participates in and upholds a legacy of cultural supremacy and exploitation. If the title didn’t indicate the musical markers of an other, I suspect that not many listeners today would be able to pick up on the musical othering because so much of the piece is stylistically appropriate to the foxtrot and features a catchy, memorable melody. It really is too bad that the piece boasts a title that, nowadays, negates any enjoyment of the music itself and instead draws attention to a history of demeaning musical marginalization.

1 Art Kahn Orchestra, Isham Jones, and Art Kahn. Shanghai Lullaby. 1923. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-672297/.

2 Norton, Pauline. “Foxtrot.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 27 Sep. 2023. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000010075.

3 Conyers, Claude. “Foxtrot.” Grove Music Online. 6 Feb. 2012; Accessed 27 Sep. 2023. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002219055.

4 Bjerstedt, Sven. “Musical Marginalization Processes: Problematizing the Marginalization Concept through an Example from Early 20th Century American Popular Culture.” Lund University, April 4, 2016. https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/musical-marginalization-processes-problematizing-the-marginalizat.

5 Ibid.