September 15, 1963. It’s a lovely Sunday morning in Birmingham, Alabama, when an explosion states the streets right outside of the predominantly African American 16th Street Baptist Church. Twenty two parishioners were injured, and four little girls were killed. It was later revealed that the bomb was deliberately placed by local members of the Klu Klux Klan, who were not persecuted until years later in the early 2000’s for their actions.2 This event, known as the 16th Street Church Bombing, is a famous event within the Civil Rights movement. It was a turning point for the Civil Rights movement, with many white citizens being outraged at the innocent people who were killed and harmed. The deaths were followed two months later by the assassination of President JF Kennedy, which caused an outpouring of national grief and ensured the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.3

The event of the 16th Street Church Bombing inspired many people towards the Civil Rights Movement, including the folk singer and songwriter, Richard Fariña, who wrote the song “Birmingham Sunday” about the event.1 Using haunting lyrics that included the full names of each girl who was killed, set to a traditional Scottish ballad, he was able to create a protest ballad that inspired mourners and justice.2 Fariña uses lyrics such as “cowardly” to describe the attackers, symbolizing and targeting the moral failings alongside the racist act.2 He also structures the song to reach both black and white audiences, using themes of mourning and giving humanity to each of the girls killed to persuade the audience that this was a tragedy of lives cut short. At the same time, he uses words such as “freedom” and language to symbolize the black church to draw in an audience of black people and Civil Rights activists.2

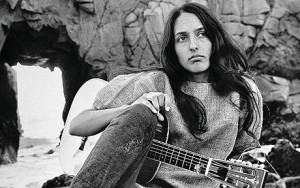

The song was popularized by Fariña’s sister in law and contemporary, Joan Beaz. Both artists were heavily involved in the Civil Rights Movement, with Baez personally marching hand-in-hand with Martin Luther King Jr. and Bob Dylan singing “We Shall Overcome.”2 Baez added complexity to the song Fariña wrote, with her haunting soprano vocals and popularizing it as the quiet protest song it grew to be.2 Baez’s popularization of the song inspired the persecution of one of the bombers in 1977, even though his fellow Klan members were not persecuted until the early 2000’s.2

The song “Birmingham Sunday” still holds a legacy today. Rhiannon Giddens, a famous bluegrass singer who thrives in reclaiming and exploring historical African American songs, recorded a cover of the song in 2017. She covered and revised the song on her album, Freedom Highway, an album inspired by the decades of protest music and social justice movements.2 Giddens’s recording of the album served a purpose in terms of protest music as well, bringing the events of the song into the public consciousness during the #SayHerName era of protest and black politics. In this more modern interpretation of it, the song serves to draw attention to how black women have often been omitted from narratives of racial narratives, and should have their names memorialized like the girls in this song, who went on to shape something they didn’t even know they did. We are unaware of the names of the girls – Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, and Carol Robertson – even though they shaped the way to the Civil Rights Act posthumously.

These three versions of the same song show how protest song can be widespread and adapted to different causes, and how different artists can interpret it in ways that make sense to their audiences and causes.

1 – https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C73912

2- https://www.jstor.org/stable/26510207?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents