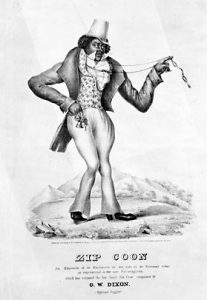

White Americans have always love nostalgia and cozy feelings of their past. What could be more nostalgic than a white family curled up on a couch watching Irving Berlin’s White Christmas? If you noticed something wrong about that sentence, good. The movie is all about nostalgia with the actors “dreaming of a white Christmas” or singing tunes such as “Gee, I wish I was back in the army.” In the film White Christmas there is an iconic scene called the Minstrel Number.

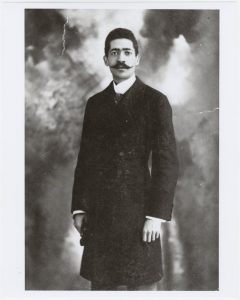

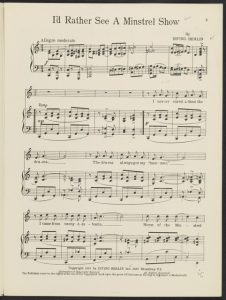

This was a song that was a medley written by Irving Berlin and performed by Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, and Rosemary Clooney. The song “Id Rather See a Minstrel Show” opens the medley when sequels into “Mr. Bones.” “M r. Bones” has Clooney singing of “minstrel men we miss” and “when Georgie Primrose used to sing and dance to a song like this.” Now Primrose was a white vaudeville song-and-dance man who wore blackface in the late 19th century. However, to really feel the effects of these lyrics popping up in one of America’s favorite nostalgic movies we have to go back to another movie of Irving Berlin with the infamous Bing Crosby; Holiday Inn; in which “White Christmas” was first sang.

r. Bones” has Clooney singing of “minstrel men we miss” and “when Georgie Primrose used to sing and dance to a song like this.” Now Primrose was a white vaudeville song-and-dance man who wore blackface in the late 19th century. However, to really feel the effects of these lyrics popping up in one of America’s favorite nostalgic movies we have to go back to another movie of Irving Berlin with the infamous Bing Crosby; Holiday Inn; in which “White Christmas” was first sang.

While Holiday Inn was released in 1942, by 1954 when White Christmas was released it was already considered ill of someone to black up their faces. In Holiday Inn there is one song in particular that stands out and is often CUT out of the movie during showings. This is “Abraham” performed by Bing Crosby in full black face on Abraham’s birthday.

All the musicians and dancers around him are also in full black face. Only 12 years before White Christmas and 12 years before performing in black face was looked down upon, black face performances amongst major mainstream stars at the time was very acceptable. This brings me to the sheet music of both “Abraham” and “I’d Rather See a Minstrel Show.” Upon researching minstrel music in pop culture I came across the beloved Irving Berlin and Bing Crosby; both loved by generations of Americans. I saw that Irving Berlin had had both “Mandy” and “Id Rather See a Minstrel Show” published in Ziegfield Follies of 1919. While “Mandy” was of easy access, the Minstrel Show number was almost impossible to come by. I spent quite some time following every bunny trail I could to get to the sheet music of the Minstrel Show number but to no avail. Recalling Holiday Inn and Minstrel themes in that movie I tried to find sheet music to “Abraham.” This piece was also surprisingly hard to find on Sheet Music Consortium and I was eventually redirected to Baylor University’s Digital Libraries before I found it.

All the musicians and dancers around him are also in full black face. Only 12 years before White Christmas and 12 years before performing in black face was looked down upon, black face performances amongst major mainstream stars at the time was very acceptable. This brings me to the sheet music of both “Abraham” and “I’d Rather See a Minstrel Show.” Upon researching minstrel music in pop culture I came across the beloved Irving Berlin and Bing Crosby; both loved by generations of Americans. I saw that Irving Berlin had had both “Mandy” and “Id Rather See a Minstrel Show” published in Ziegfield Follies of 1919. While “Mandy” was of easy access, the Minstrel Show number was almost impossible to come by. I spent quite some time following every bunny trail I could to get to the sheet music of the Minstrel Show number but to no avail. Recalling Holiday Inn and Minstrel themes in that movie I tried to find sheet music to “Abraham.” This piece was also surprisingly hard to find on Sheet Music Consortium and I was eventually redirected to Baylor University’s Digital Libraries before I found it.

These two pieces are important as they bind exemplify some of America’s most beloved actors and song/screenwriters. They humble us as they remind us that none of us were too good for blackface and the enjoyment America wrongfully sought in it. It also reminds us of how minstrelsy and still be in pop culture of today and the elements of life that are important to our cultures.

Library Of Congress. (n.d.). I’d rather see a minstrel show – library of congress public domain search. Library Of Congress. Retrieved October 26, 2021, from https://loc.getarchive.net/media/id-rather-see-a-minstrel-show-2.