It is interesting that when a majority of us think of Bluegrass music, we immediately think of it being white music, from the south, and “hillbilly.” After listening to and reading the transcript from Rhiannon Giddens’ keynote address, I found that she also had the idea that there is “whiteness” in Bluegrass (specifically the banjo), although she doesn’t use the term “whiteness,” the picture that was portrayed to her was that Bluegrass originated from white people in and around the south.

An important quote from Rhiannon Giddens

“This was not the picture I was painted as a child! I grew up thinking the banjo was invented in the mountains, that string band music and square dances were a strictly white preserve and history – that while black folk were singing spirituals and playing the blues, white folk were do-si-do-ing and fiddling up a storm – and never the twain did meet – which led me to feeling like an alien in what I find out is my own cultural tradition.”1

We should take note of the origins of Bluegrass. Where did it originate? Who was playing where? These are questions that most of us think we know the answer to but are in fact actually quite wrong. Bluegrass has origins that date back to as early as 1780 in Greenville, South Carolina. A majority of this music had a widespread diaspora throughout Southern Appalachia, the most notable state would be Kentucky, where the Blue Grass Boys band originated.These answers show that Bluegrass was coined by white people and that it has white origins. From listening to Giddens’ keynote address, we find these answers to be untrue.2

Another quote from Giddens

“But the black to white transmission of the banjo wasn’t confined to the blackface performance. In countless areas of the south, usually the poorer ones not organized around plantation life, working-class whites and blacks lived near each other; and, while they may have not have been marrying each other, they were quietly creating a new, common music.”1

Bluegrass music can’t be white. Although the media would say otherwise, Bluegrass music has origins from all throughout Southern Appalachia, whether it be from white people or not. White men used what they heard from African Americans and put their label on it, claiming it as their own. In other words, it’s okay when white people sing and play African American “blues” or “bluegrass” because it is entertaining but when African Americans are the ones performing, it is considered as “lazy,” used as “complaining” songs, and simply not good.3

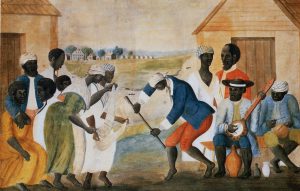

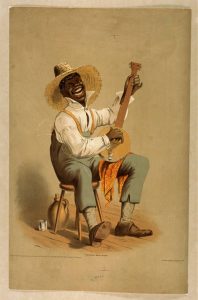

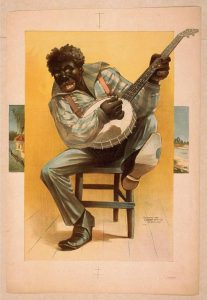

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it.

This first photo is taken from a popular (in the 1800s) cartoon by Currier and Ives called Blacktown, a satire aimed at making fun of black people. Its one of the first images that results from the search of the word “banjo,” yet we know that banjo was a popular instrument in black communities. Its a useful source to pair with Southern and Gidden’s points, because it places the banjo in the black musical canon, yet it’s entirely controlled by the white people who made it. This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.

This picture, from 1901, is of a “picaninny” performing child, a popular vaudville act, in which children performed for white spectators, often for humor, under the hand of a white adult female. The children often travel with the troupe without their families. Again, the mandolin places the instrument into the black music narrative, but the picture is likely taken by a white person for other white people. I find this picture especially disturbing, as the child is nameless, naked, and smiling (is she happy?). She is viewed as an object for entertainment; property to the act. This is another example of white people in control: not only of the picture and narrative, but of the life of this child.

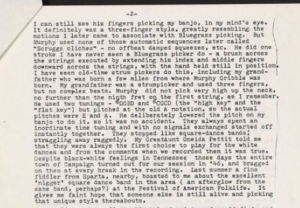

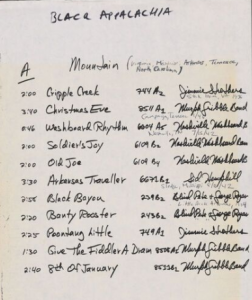

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]